Santa Cruz Geology and Paleontology

Watch VideoA Guide to Local Rocks and Fossils

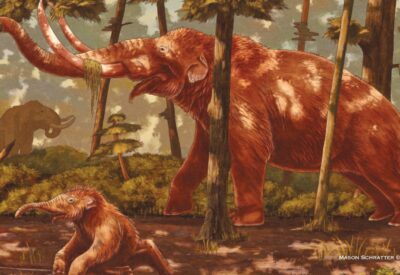

Santa Cruz is an area of geologic interest with a complex history of processes that shaped the landscape and the fossils we see today! Wind, waves, earthquakes, fires, and other natural forces have changed and shaped the region for millions of years. Every inch of this county was under the ocean mere millions of years ago — in an afternoon you can watch whales breach in the ocean and look at the fossilized remains of their ancestors on the beach (or high up in the mountains for that matter).

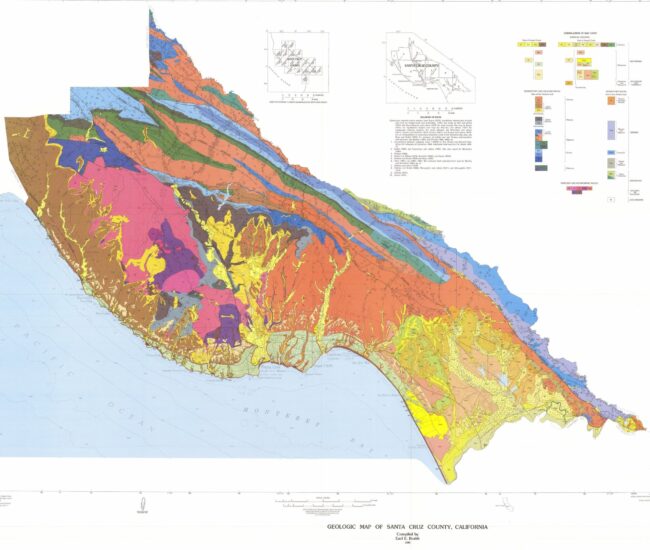

Geologic Formations

This map shows the distribution of different rocks in Santa Cruz County. Each color represents a different kind of rock and, in turn, a particular age. Many of these rocks represent formations.

A geological formation is a basic unit that geologists use to group rock layers. Each formation must be distinct enough for geologists to tell it apart from surrounding layers and identify it on a map. A formation can consist of a variety of related or layered rocks, rather than a single rock type. There are over 14 geologic formations in Santa Cruz County, four of which are well known for fossils. Most of these formations were created through movement of the crust due to tectonic uplift at the subduction zone off the California coast.

Much of the county is underlain by granitic rock that formed about 100 million years ago from molten rock which cooled very slowly at a depth. Since then, this area has been covered by the sea much of the time. Sand, mud and other sediment was deposited on the seafloor and was eventually compressed and hardened into sedimentary rock which was uplifted to form the Santa Cruz Mountains. Many of the sedimentary beds, which were originally horizontal, have been tilted, folded or partly eroded away, and in some areas major faults have offset the rocks.

Fossilferous Formations

Purisima Formation (3-7 Ma)

This sandstone formation was deposited at shallow, near-shore conditions, which is why it has a coarser composition than the Santa Cruz Mudstone it followed. The blue-gray sandstone primarily consists of sediment deposited from rivers dumping into estuaries and bays.

FOSSILS

If you find a fossil on a beach in Santa Cruz County, it is most likely from this formation. The Purisima Formation features dozens of species of invertebrate fossils, especially mollusks, as well as cetaceans and pinnipeds (i.e. whales and seals).

WHERE

Though there are outcrops of this formation north of Santa Cruz, within the County this formation can be found from where Merced Avenue intersects West Cliff Drive in Santa Cruz down to the cliffs of Seacliff State Beach. The best way to find fossils from this formation is at low tide on the beaches below Depot Hill in Capitola, between Capitola Beach and New Brighton Beach. Look to the cliff walls and through boulders and smaller rocks littering the sandy shore.

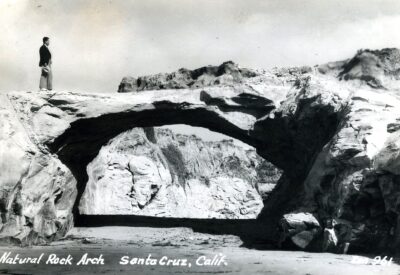

Santa Cruz Mudstone (7-9 Ma)

While the Purisima Formation formed from shallow-water sediment, the Santa Cruz Mudstone formed farther out at sea where the sediment consists of finer silt and clay. This formation has a more yellow tone and is often patterned with rusty red cracks, caused by methane seeping through the rock while it was still under water.

FOSSILS

Finding a fossil in the Santa Cruz Mudstone formation is a much trickier task than the Purisima Formation that overlays it (in parts), but there are fossils to be found. While most are small bivalves (i.e. clams) and echinoids (i.e. sand dollars), O. megalodon teeth have been found in this Formation.

WHERE

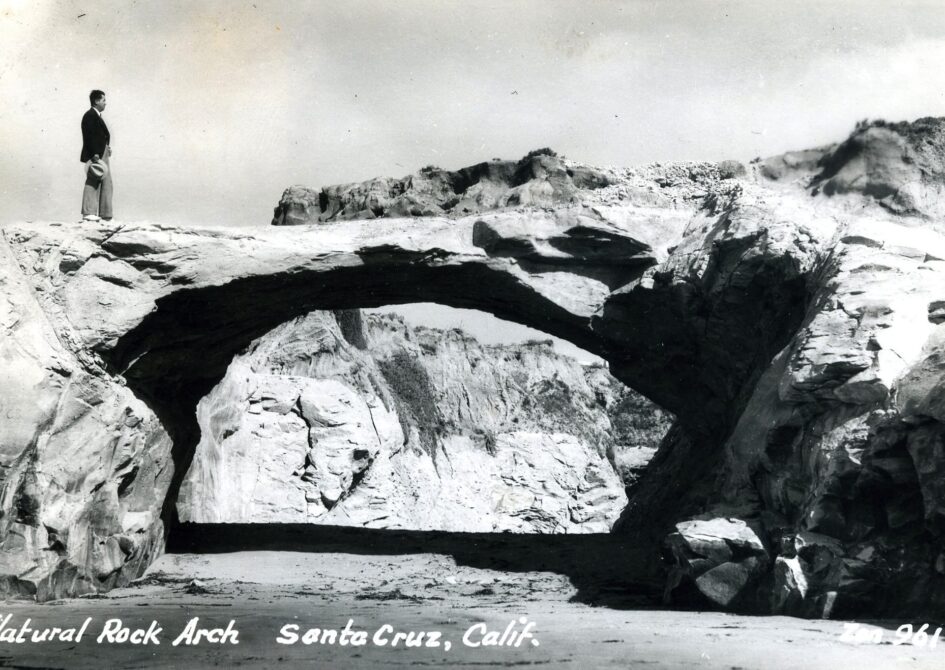

The arch at Natural Bridges State Beach is Santa Cruz Mudstone, as are all of the cliffs up the coast from there until just before Año Nuevo, with a visible outcrop at Swift Street off of West Cliff Drive.

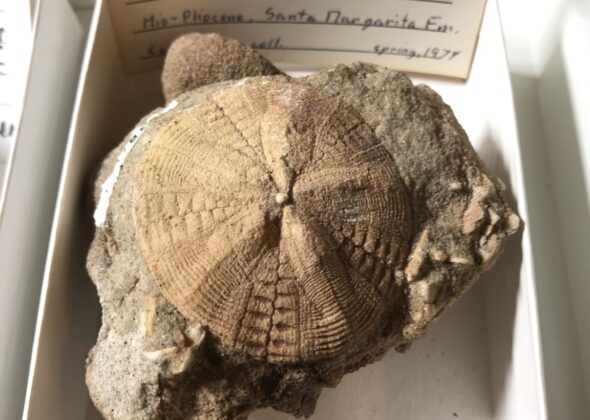

Santa Margarita Formation (10-12 Ma)

FOSSILS

Some of Santa Cruz County’s most magnificent fossil finds have been unearthed from the Santa Margarita Formation. According to Frank Perry, “Fossils of at least 20 species of sharks and rays are present, as are remains of bony fishes, marine mammals such as sea cows and sea lions, and invertebrates including mollusks and sand dollars.”

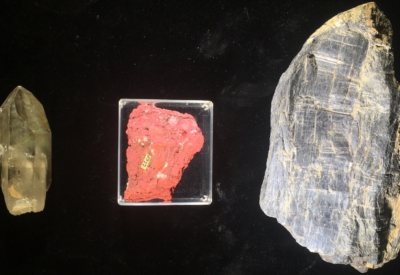

ON EXHIBIT

Features from this formation on display in our exhibits are a cast of a fossil sea cow, an O. megalodon tooth, a jaw bone from a baleen whale, and a dig-box of sand dollars.

WHERE

There are outcrops of this formation in the lower parts of the Santa Cruz Mountains all the way up to Año Nuevo, but in Santa Cruz County we find it mostly north of Santa Cruz, through Scotts Valley and up to Boulder Creek. The rare Santa Cruz Sandhills habitat consists of sediment from this formation.

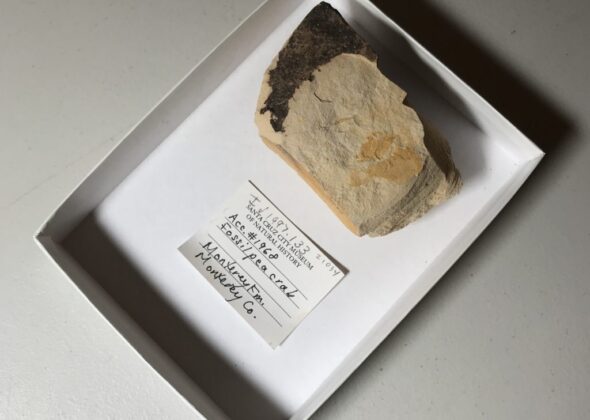

Monterey Formation (17.5-6 Ma)

The Monterey Formation is a Miocene deposit rich in organic material. While it might not reveal fossils of charismatic megafauna like the Santa Margarita formation that followed, the Monterey formation has other interesting biotic features. Monterey Chert, used for tools by Indigenous peoples along the coast for thousands of years, is a feature of the Monterey formation. Chert is extremely diatomaceous (contains high quantities of organic material from plankton), and under other conditions could have become oil. Regularly occurring controversies regarding drilling for oil in the Monterey Bay are due to the presence of the diatom-rich Monterey Formation.

FOSSILS

All of the above notwithstanding, there are micro-fossils to be found. Fossils of diatoms are only visible under a microscope, but fossils of some fish fragments and mollusks are (a little) easier to find. The example from our collections above is a fossil pea crab.

WHERE

There are outcrops of this formation throughout the Santa Cruz Mountains — and throughout California. Oil drilling operations off the coast of Southern California and even inland are removing oil from the Monterey Formation. In Santa Cruz County, you can explore this type of rock on parts of Ben Lomond Mountain, along Lompico Creek, and at Majors Creek Canyon.

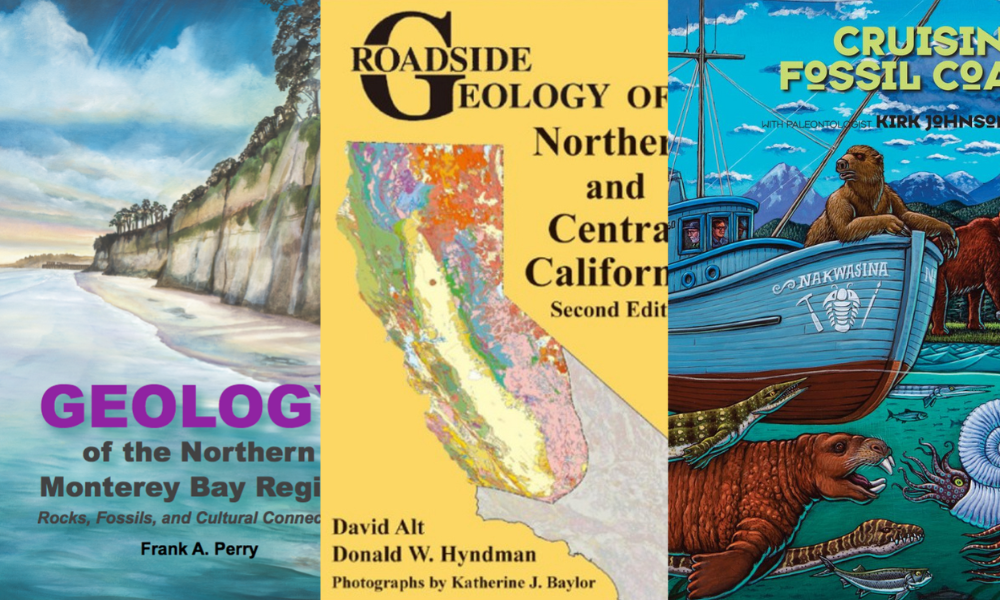

Your Rock and Fossil Questions Answered

It could be a fossil bone or shell, or it could be a uniquely weathered stone. Explore the resources listed here or email a photo and detailed description to us at collections@santacruzmuseum.org. You can help us identify your object if you:

- Include a scale in your images, ideally not something that is relative in size like a hand or a banana, etc.

- Take pictures or videos from multiple angles. For skulls, seeing the teeth is important.

- Provide some general information on where you found it.

Please do not bring any specimens to the Museum without first making an appointment.

When collecting anything from nature, always practice the “Know Before You Go” philosophy. Determine who manages the land you are on and their laws.

Vertebrate fossils (including all mammals like whales and mastodons) are protected on all public lands and require a permit for collecting. In California, plant and invertebrate fossils on non-federal public lands are also protected. This means that you are not allowed to collect fossil shells embedded in rock from Capitola and Aptos beaches without first getting a permit from the appropriate agency (either County or State Parks).

In addition to knowing if you are legally allowed to collect, consider that when you collect an object, you are removing it from its context — without good data, it’s unlikely that specimens can be used for science. Every specimen collected from nature impacts the surrounding ecosystem which is why certain species and properties are protected.

If you find something interesting, rather than collecting it, you can leave it where you found it, take a picture, and notify the agency whose property you are on and/or the Museum. Fossil shells around Capitola are incredibly common, but if you find something unusual that doesn’t seem to be commonplace, it might be worth getting in touch with us.

If you’ve found something that you would like us to take a look at and help you identify, take a photo and send it to collections@santacruzmuseum.org. Be sure to include something for scale and mention where you found it. The museum cannot physically accept objects without prior consent. If you’re interested in donating your specimen to the Museum, our collections staff will need to first assess how it fits within our collections policy.

There are a few things to consider when determining if the object you have found is a (fossilized) bone or a stone.

- Where was it found? If it was in your lawn, it’s probably a rock. Consider what rock formations are around you and how old they are.

- Look at the texture. A rock will either be made up of packed sediment or crystalized minerals, whereas a fossilized bone will likely show evidence of the canals and webbing featured in actual bone.

Discarded bones have canals and webbing within them that are hollow. If the bone has fossilized, this texture will likely still be in evidence, but it will have been “filled” by mineralization. This also means that fossilized bones will likely feel heavier. Depending on how the bone fossilized, it may also have an altered color. BUT dark coloration does not necessarily mean it is a fossil — recent bones can also turn dark just by being under deep sand where the environment is anoxic.

That cool thing you found in Santa Cruz is undoubtedly cool, but we gotta tell you — it’s not a dinosaur. Our landscape in Santa Cruz was still millions of years away from forming when the dinosaurs were alive in the Mesozoic era, 248 to 65 million years ago.

Fossil eggs of any kind are incredibly rare and more often than not, what looks like an egg to our eye is just a concretion, minerals that form a rounded mass around a harder object like a pebble or a fossil.

The probability of finding a meteorite on the earth’s surface isn’t very high. When meteorites are found on the earth’s surface they tend to be in very specific spots, such as Antarctica, where they are easy to spot on the surface and they are less likely to erode, and deserts. If you do find an object that might be a meteorite you want to look out for a fusion crust and regmaglypts (concave dimples) on the surface.

You can use this self-test check-list at home to investigate your find: https://sites.