Humphrey Pilkington, First California State Park Warden

As many folks know, today’s Seabright was shaped, in part, by various members of the Pilkington family. From Thomas Pilkington, who developed beachfront Seabright into summer spot Camp Alhambra in the 1880s, to Thomas’ son James who built the first bathhouse at Castle Beach, to James’ brother T.B. who subdivided the family property, naming Pilkington Avenue in the process. But it is Thomas’ nephew Humphrey whose legacy secured the Museum’s home here in Seabright.

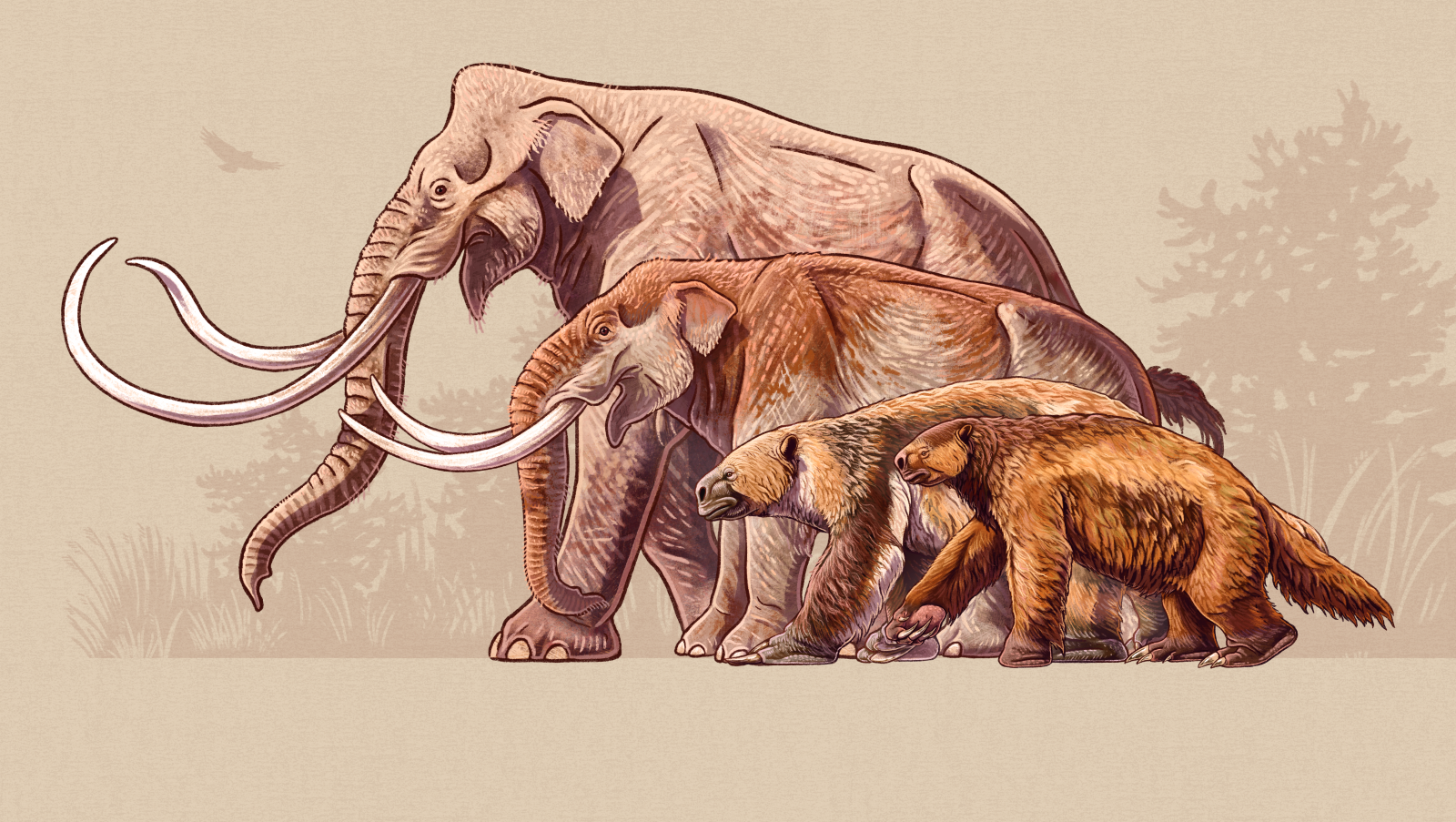

John Humphrey Blakey Pilkington was born in Illinois around 1858, emigrating to Santa Cruz with his parents in 1871. As a young man Humphrey studied agriculture at the University of California — knowledge he would put to work on his family’s orchards above what is now Delaveaga Park. His love for the landscape was not restricted to agriculture. Humphrey was well known for organizing walks from Watsonville through the mountains to San Jose, leading vacationers on tours of Yosemite, and co-hosting an annual picnic under the canopies of the beloved Big Trees.

The turn of the 18th century was an invigorating time for lovers of the local redwood forests — an 1899 fire galvanized community commitment to conservation, with folks like writer Josephine McCracken and photographer Andrew P. Hill pooling their talents to advocate for preservation of old growth redwood trees. The founding of the Sempervirens Club and the support their members drummed up were critical to the birth of California Redwoods State Park in 1902.

In July of 1903, Humphrey Pilkington started as warden of the park, whose name was not officially changed to Big Basin until 1927. Local papers praised this choice, including the Santa Cruz Evening Sentinel, which noted in April 1903 that “The people of Santa Cruz county take a pardonable pride in everything that pertains to [Big Basin] and they are naturally interested in seeing its management placed in the hands of careful, conscientious and competent men.”

In addition to his work as an orchardist and forester, as well as various civic posts, Pilkington brought to the table years of voluntary service for the Santa Cruz Fire Department. These were fortunate skills to have in an unfortunate time — in September 1904, another fire swept through the mountains. Burning for 20 days, this fire proved famously stubborn, even reigniting into the following year. Impacting more than 3,000 acres of the park, the fire fueled fear and heartbreak even amongst those whose homes and lives were not in direct danger.

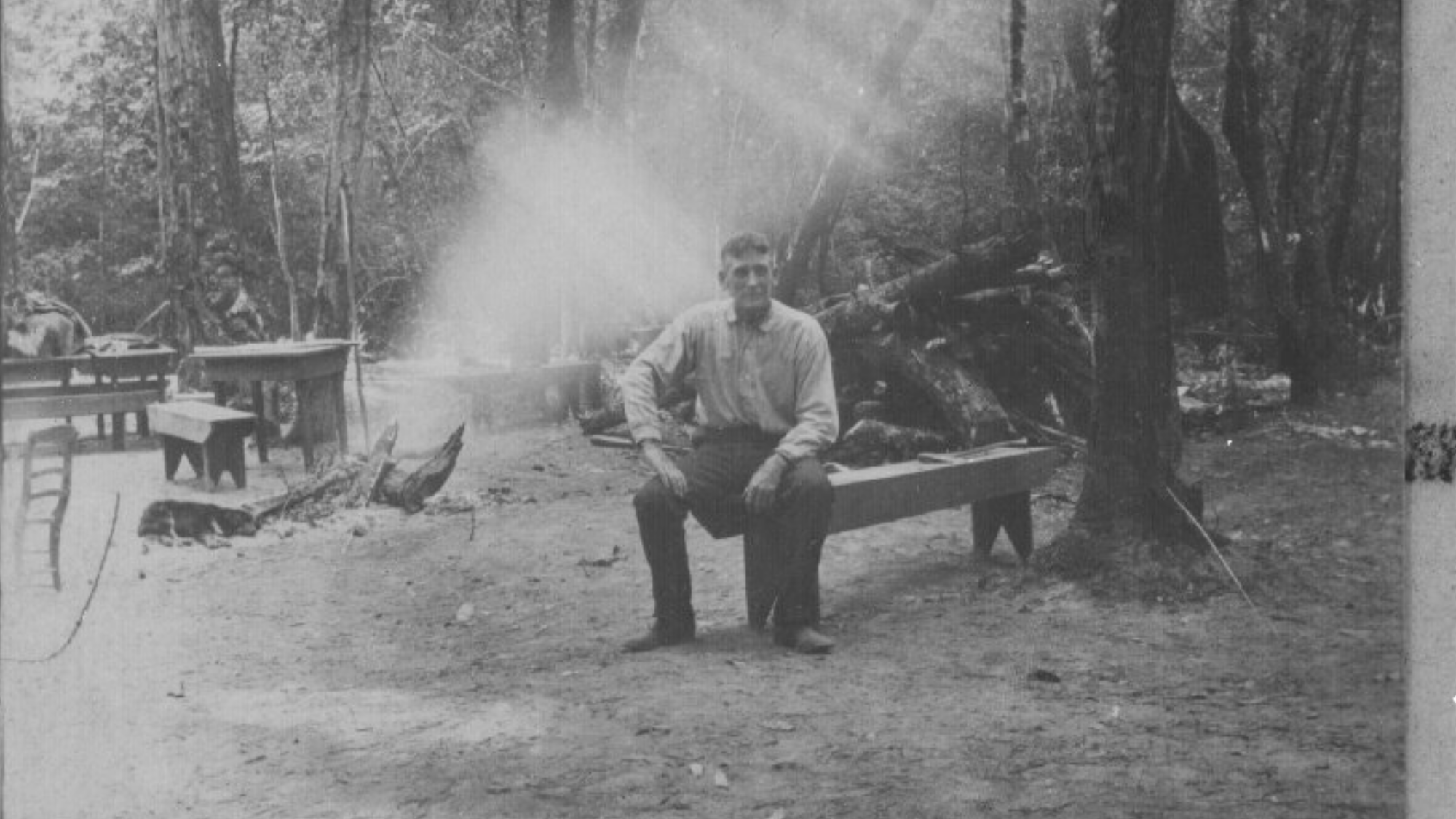

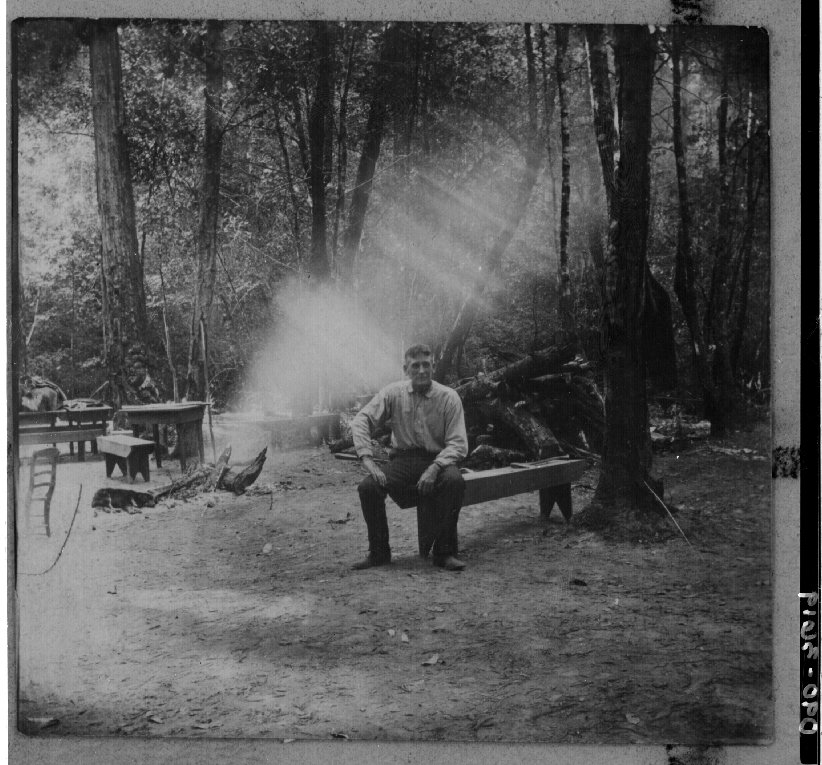

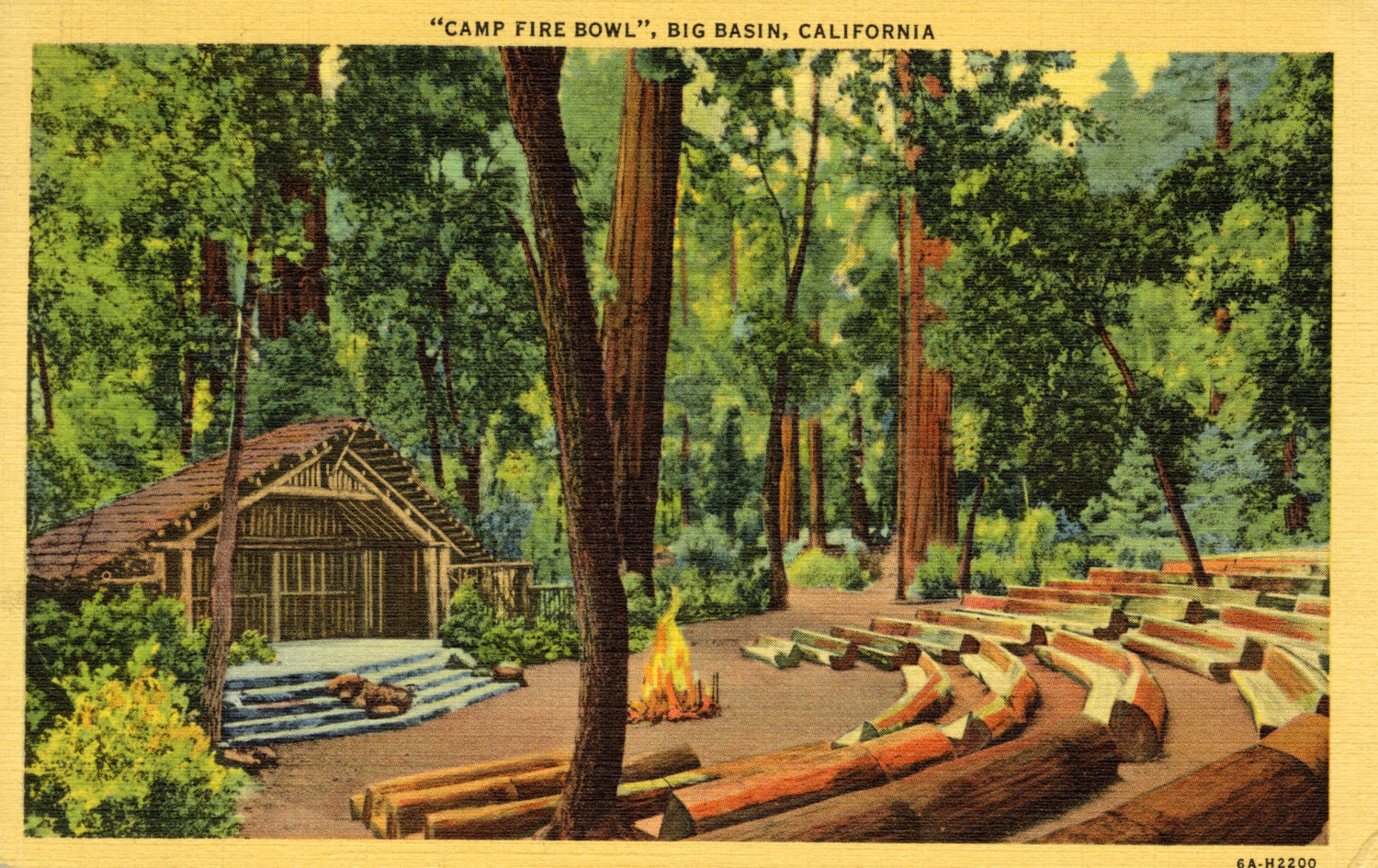

In the midst of the fight, Warden Pilkington did not change his clothes or sit down to a meal for nine days. Composed of up to 100 volunteers, firefighting crews focused their efforts on Governor’s Camp. This set of buildings was originally built to share the wonder of the Big Basin area with visiting California governors, in order to inspire government support for the park. They were ultimately successful, and these park buildings would later be developed into structures like the Campfire bowl, featured on this popular postcard. Last year’s CZU Lightning Complex fires echoed this historic fire, but with more intensity, given the current climate. The CZU fires burned through 97% of the park, sparing none of the contemporary structures that enhanced park access, which now must be reimagined.

Despite his widely praised management of the park, Pilkington was replaced as Warden in 1907 for political reasons. Ironically, while Pilkington had heroically fought the 1904 fire as the first warden of a California state park, his successor Sam Rambo would be found complicit in schemes to remove living trees under the guise of cleaning up damage from the 1904, and was the first state park warden to be fired in disgrace.

Pilkington’s departure from guardianship of the park did not extinguish his interest in nature, and he continued to be a student and collector of natural history. However, the collection he bequeathed to the City of Santa Cruz upon his death consists mostly of Indigenous stone tools and baskets. He developed his collection at a time when many EuroAmerican collectors were engaged in obtaining objects made by Native Americans under the racist impression that they were primitive peoples on the verge of extinction.

This collection was integral to the formation of our Museum here in Seabright. Pilkington’s gift was conditional upon the establishment of a formal museum, and the community rallied around the formation of a Museum that combined the Hecox collection and others under one roof where they could be better cared for.