It’s a Date! — Carbon Dating Fossils

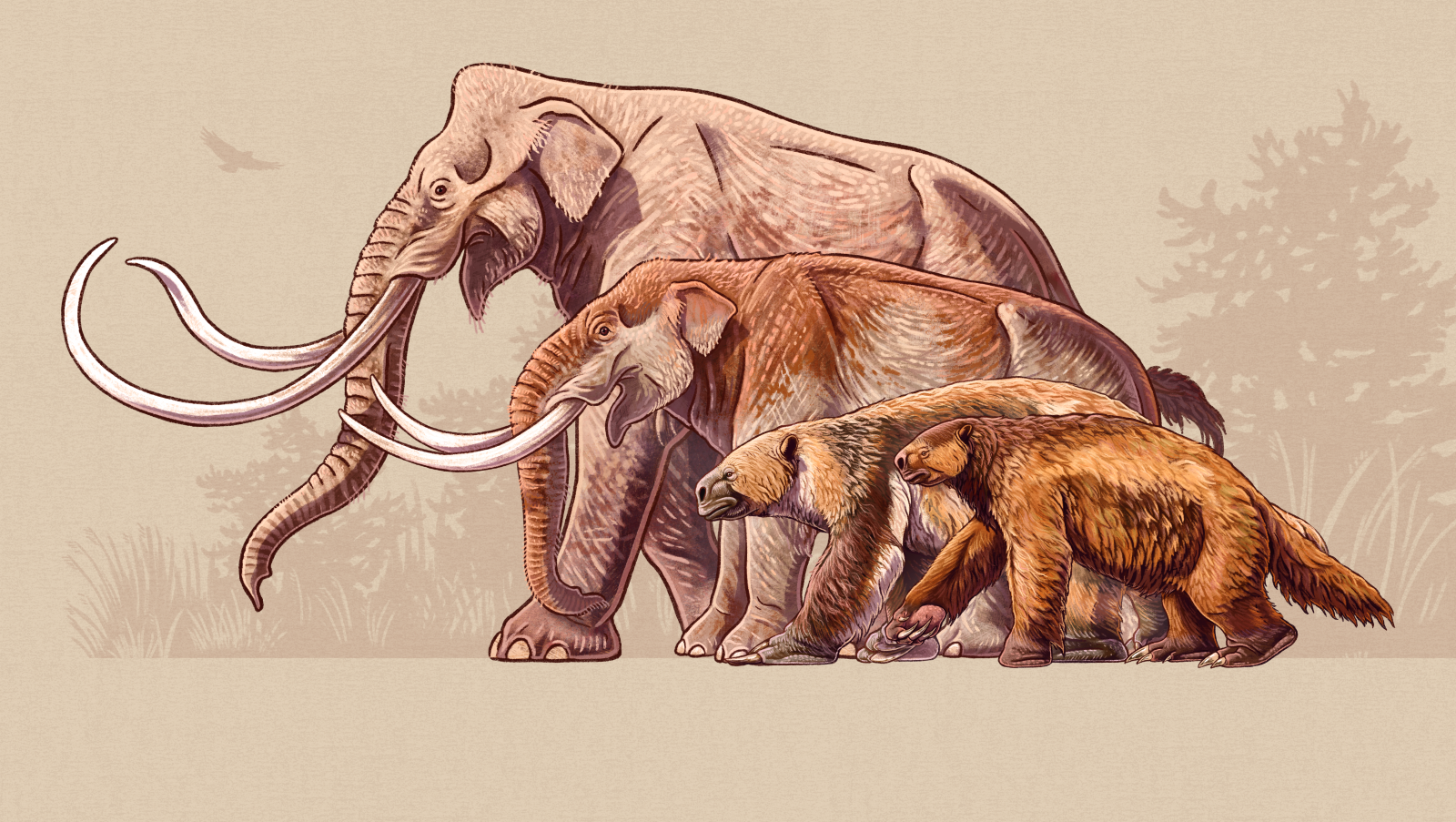

Summer may be coming to an end, but we’ve still got some hot gossip here at the museum: we have a date! In fact, two dates! And for some of our favorite fossils no less: the Pacific mastodon molar tooth that captivated our community and made global news in 2023, and the 1980 Pacific mastodon skull that has become a beloved component of our permanent exhibits.

In actual fact, we have a bit more than two simple dates, we have median dates with a certain amount of statistical uncertainty. The adult mastodon tooth clocks in with a most likely date range of between 12,100 and 11,800 BC, with the strongest probability around 11,974 BC. The juvenile mastodon skull clocks in at a most likely date of 11,320 BC, within a window of 11,460–11,220 BC. That’s close to the end of the Pleistocene, close to the extinction of the Pacific Mastodon, and concurrent with known human settlement in what is now called California (link to max blog).

These results were made possible through the radiocarbon dating process, via the generous work of UCSC paleontologist Paul Koch and his team, along with the wonderful folks at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. Radiocarbon (Carbon-14) dating, a complex process in which the steady rate of decay in certain types of carbon atoms from tissues of formerly living things is measured against background environmental carbon levels under a specific set of assumptions, and is a form of absolute dating. Absolute dating describes methods that estimate the specific age in years of a particular specimen, and is often the kind of data people are looking for when they ask how old a fossil is.

But as we all know, you don’t always get what you’re looking for when it comes to dating. It’s important to note that not all types of dating are appropriate in all situations. Carbon-14 dating is only a good method for organic materials up to about 60,000 years old, after which there is no longer enough radioactive material to test; it has all been converted from the unstable form of carbon to a stable form of nitrogen.

You may not get absolutely what you’re looking for, but you also may get something else that’s useful in its own way. In addition to many other types of absolute dating methods, there are also types of dating methods referred to as relative dating. Relative dating is a way of estimating a specimen’s age based on the context in which it was found. An important and early (in the human science time scale) type of relative dating has been the use of index fossils, organisms known to be found in specific geologic layers , to place specimens in relative chronological order in the fossil record.

Age may just be a number, but it also helps us better understand the specific context of individual specimens in our collections and the stories they tell. Alton Dooley, head of the Western Science Center, was excited to learn of the dating results for both the tooth and skull. Together they are some of the geologically youngest specimens he is aware of having been found in California. (And he would know – having surveyed existing West Coast specimens extensively in the process of identifying the Pacific Mastodon as a unique species.) This means the mastodons from Santa Cruz could be used to help flesh out the story of the final days of this species on Earth.

The tooth is currently undergoing final stage conservation with specialists at the Western Science Center, whose staff have extensive experience working with mastodon fossils and other Ice Age material found during the excavation of Diamond Lake, in Riverside County. We are excited to keep the museum community updated on the specimen’s progress, as well as additional mastodon material that is being conserved at the Western Science Center.

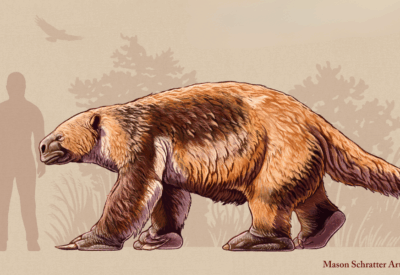

In the end, dating is an opportunity for a new perspective. We invite you to come visit the museum for our Pleistocene Pop Up (September 30 – October 12, 2025), not just to see our new sloth specimen, but also to see old standards with new eyes.