Natural History in the Palm of your Hand

By Gavin Piccione and Graham Edwards

Even the smallest and most seemingly ordinary rock tells a story about the processes that have shaped the area in which it is found. From this point of view, beaches are a massive archive of the geologic history of a landscape that contains tiny samples of all the rocks that make up the surrounding area.

The Geology Gents (Graham and Gavin) spend a day at the beach exploring the natural history of Santa Cruz, looking only at the sand and rocks that fit in the palm of their hand.

Join the “conversation” below as the Geology Gents chat about what they see when they look at the sand.

Building Beaches through Erosion and Transport

Graham: For all of the attention that beaches get as beautiful places to go lay in the Sun, they really are interesting geologically.

Gavin: We usually think of beaches as a geomorphic landscape: a product of the movement of wind and water and how it shapes and transports geologic material. We don’t usually talk about them as geologic.

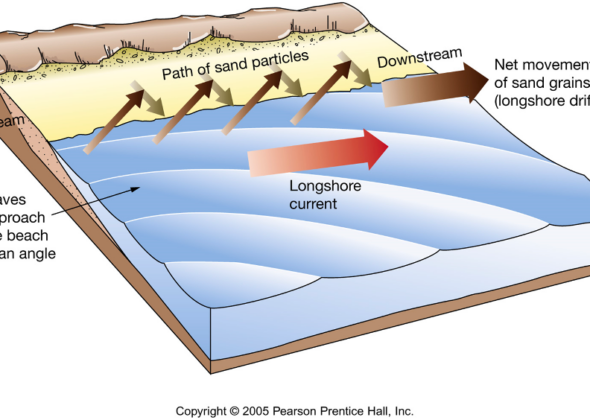

Graham: We talk about sea cliff erosion and longshore currents that move sands from these cliffs, as well as nearby rivers and streams. The longshore currents carry their sediment load along the coastlines, and pile them up in certain “low-energy” places, that we call beaches.

A Far-Reaching Collection of Rocks

Graham: But for all our talk of beaches as products of weathering (the breakdown of geologic material) and erosion (the transport of geologic material from one place to another), are they not, my friend, still rocks and something of lithologic interest?

Gavin: Lithology: the study of the characteristics of different rocks and rock types. Well, this sand is made up of rocks, and if we can identify the rock types and note their other properties, then we might be able to determine some interesting things about the geologic origins, or provenance, of these sands, as we often do with larger rocks.

Graham: Let’s take a handful then and look more closely at these sand grains.

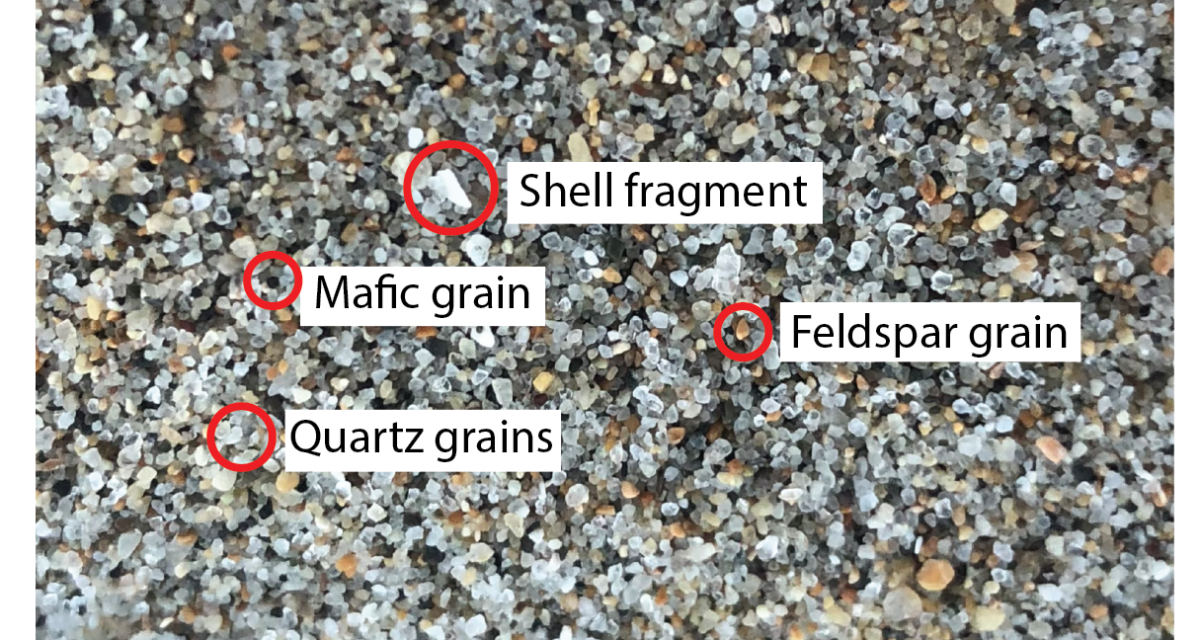

Gavin: The sand grains are mostly round. Many are clear and glassy looking, some with a smoky dark grey color. We are familiar with this mineral of course. Quartz!

Graham: Some are blocky looking and cream-white to pinkish in color. Another favorite! Feldspar!

Gavin: Those light-colored feldspars and quartz make up most of the sand, but there are a few other darker minerals. Dark flaky sheets of biotite, black grains of other mafic minerals like amphibole or pyroxene, and some greenish looking minerals – these could be pieces of serpentinite (a Central Coast favorite!) or glauconite (fossilized ocean muck).

Graham: You know, the relative abundances of these minerals really tell you something about how certain rock and mineral types survive the weathering and erosion process. The feldspar and the quartz, especially, are relatively rugged minerals that resist being broken down by the chemical actions of water and the mechanical actions of tumbling around in rivers and waves. But the greenish and darker minerals, which are less resilient to weathering, are very rare. Most of them have been crushed or dissolved to far smaller sizes and have been swept out to sea.

Gavin: So a lot of this is geomorphology? This crushing and grinding of sediments down as they tumble through rivers and waves crash over them along the coast?

Graham: Without question, the erosive forces that shape beaches matter a great deal. If many of these rocks come from the Santa Cruz mountains, they have travelled a great distance and been worn down along the way. Their small size and rounded, almost smooth shapes speak to this long journey.

Gavin: And these pebbles? They are much larger and have sharper angles. There are pieces of mudstone, limestone, and fine and coarse sandstones. Common rocks found along the coast here. Likely these came from sea cliffs nearby that were worn by waves. Since these have not had to travel so far, they have not been weathered quite as much.

Graham: Yes, only the closest rocks can survive in pebble form.

Mudstone and Limestone

Sandstone

Limestone

Conglomerate

A Hint at the Tectonic History of California

Gavin: And yet, there is one pebble type here that is not familiar from our coastal outcrops: these granite pebbles. Where could these come from?

Graham: Well, granite, made up mostly of quartz and feldspar with large interlocking mineral crystals, is particularly durable when it comes to weathering. Perhaps it has survived a longer journey than the other pebbles.

Gavin: But from where? These granites remind me of the granite of the Sierra Nevada.

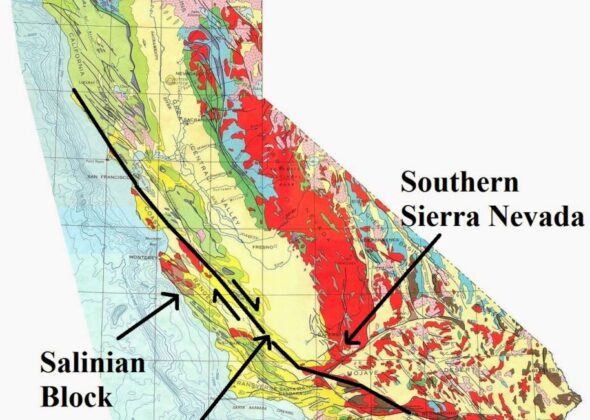

Graham: That must be granite from the Salinian Block! Carried up from the region of today’s southern California by the San Andreas fault. These granites formed along with the rocks of today’s Sierra Nevada over 100 million years ago in huge magma chambers. Over the last 30 million years, the San Andreas fault has carried the Salinian block up to the northwest, pulling rocks from the southern extents of the Sierra Nevada along with it.

Gavin: Ahh, and so the Santa Cruz mountains are full of this granite! So that’s where all this quartz and feldspar are coming from?

Graham: That’s right! The “basement” rocks of the Santa Cruz mountains are these Salinian Block granites overlain by sedimentary rocks and metamorphic rocks of the last 30 million years or so. Quartz and feldspar sands come mostly from the granites, though some may be recycled from sandstones.

Gavin: How efficient, that sands from ancient beaches are weathered out of sandstones and returned to beaches today.

Graham: And bits of serpentinite and mafic minerals are also weathered out of other rock types and incorporated into the sands.

Gavin: So the sands at these beaches are not just the result of wind, rivers, and waves. They’re the whole of the Santa Cruz mountains and even nearby coastal cliffs, ground to fine grains and mixed well.

Graham: When we take a trip to the beach and sit in the sand, we really do find ourselves in the rocks of the Santa Cruz mountains. And while it’s a little bit harder to see and recognize each individual rock, when you look closely you can see each little bit of it.