Harlan’s Ground Sloth: An Ice Age Giant

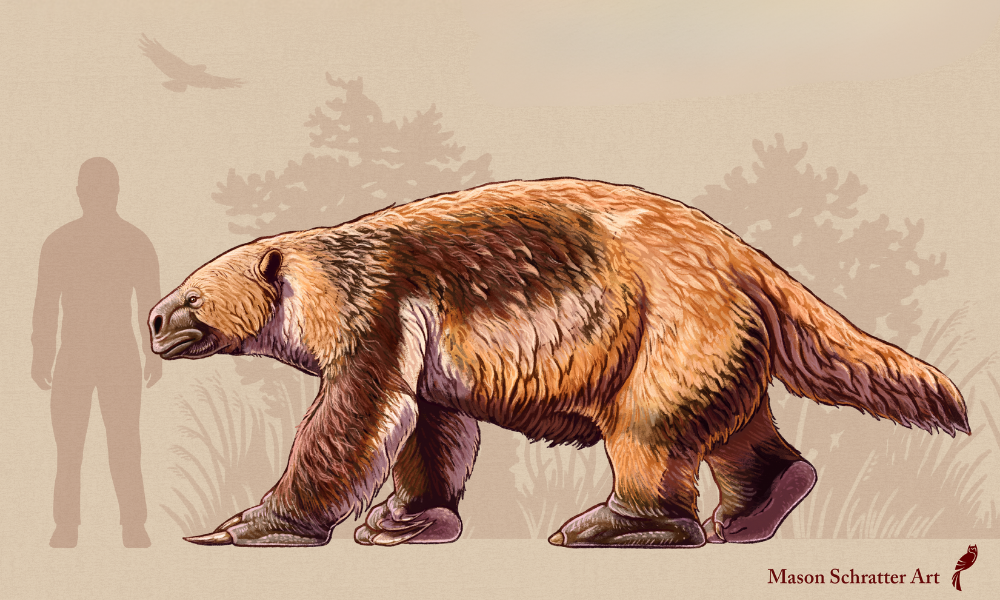

If you lived in North America 20,000 years ago, you might have crossed paths with a Harlan’s ground sloth (Paramylodon harlani), a creature unlike anything alive today. Imagine a sloth the size of an elephant, not dangling from trees but lumbering across the landscape, stripping plants and leaving behind some of the strangest footprints ever discovered. While encounters with these giants are long gone, for the first time in thousands of years, you can meet one, through our exciting new ground sloth fossil discovery, featured in the Pleistocene Pop-Up, on display September 30 – October 12, 2025.

The first discovery of Paramylodon remains occurred in 1831 in Boone County, Kentucky, by paleontologist Richard Harlan, for whom the species is named. In the years since, Harlan’s ground sloth remains have been found widely distributed across the U.S., especially in western states, with large deposits discovered in California and New Mexico, and outliers as far north as Iowa. The Harlan’s ground sloths wandered the open grasslands of North America during the last Ice Age, in a time called the Pleistocene (c. 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago). They roamed areas with plenty of water near rivers and lakes, where they could find grasses, shrubs, and flowering plants to eat.

The Paramylodon harlani’s body was built like a tank, possessing a short neck, wide chest, and powerful jaws with high-crowned molar-like teeth. Its muscular arms and legs ended in three sturdy claws, probably better suited for digging roots and pulling down branches rather than fighting. This digging behavior in search of food added grit to the diet, which may have been one factor influencing the evolution of their extremely high-crowned teeth, perfect for tackling tough tubers (SDZG, 2025).

In the dried lakebed of Alkali Flats, New Mexico, you will find crescent-shaped prints left by Harlan’s inward-turning feet. These tracks tell us that the sloth didn’t walk on the flat of its feet, but instead walked on the sides of its insteps, turning its back feet inward and giving it a slow, waddling gait, swaying from side to side as it walked, a gentle giant making its way across the landscape. Check out this 3D modeled walk cycle made by researchers at the La Brea Tar Pits to visualize.

Like its distant relatives, the modern armadillo, Harlan’s ground sloth wore a coat of rough brown fur with nickel-sized bony plates called dermal ossicles under its skin for protection (NPS, 2016). And while today’s tree sloths weigh about as much as a house cat, Paramylodon harlani could stand up to 9 feet tall and weigh over 2,200-2,400 pounds (SDZG, 2025), that’s as heavy as a small car!

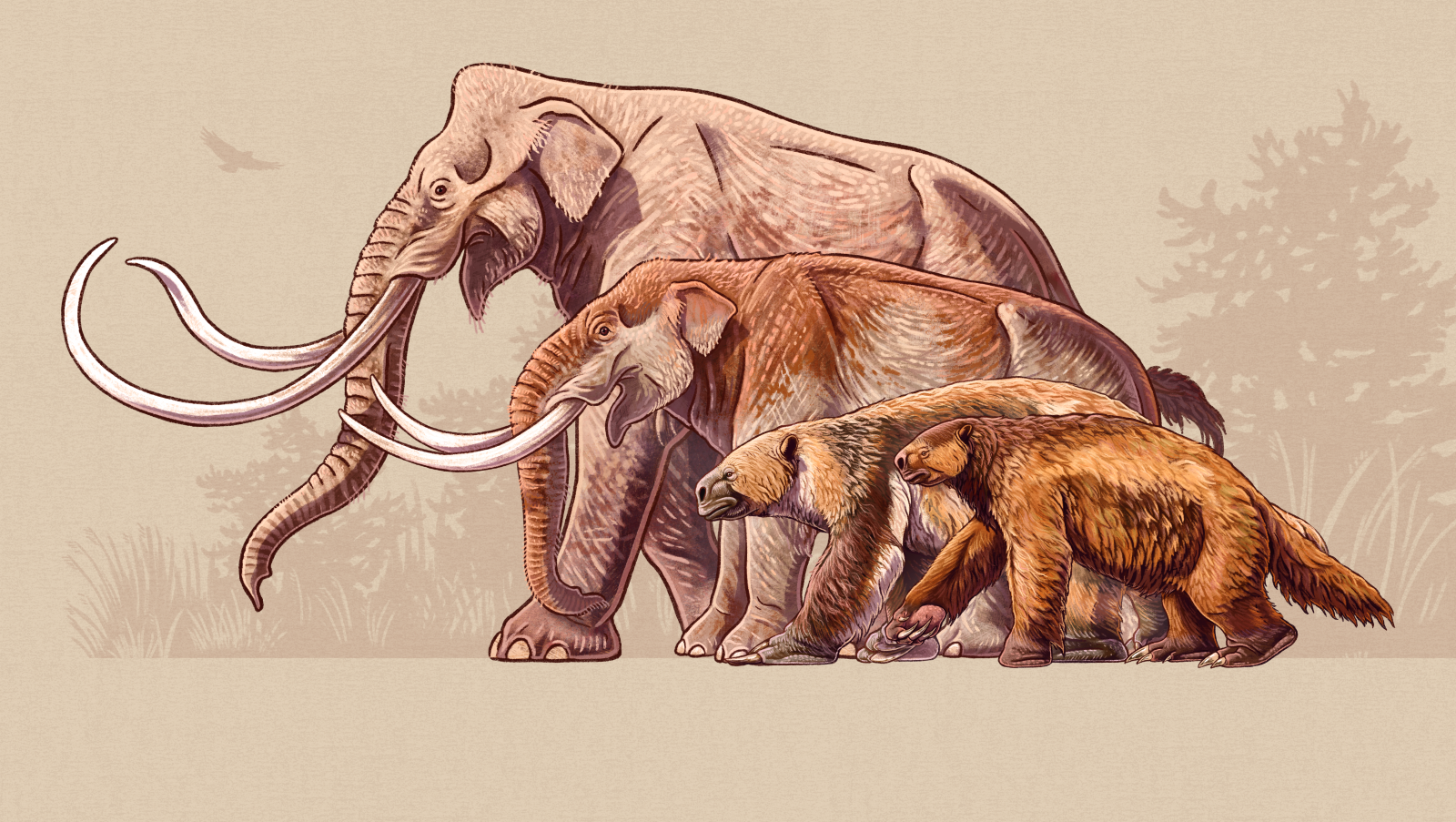

Even with its massive build, the Paramylodon harlani was only “mid-sized” compared to other ground sloths of the Ice Age. The diversity of sloths in the fossil record is high; over 100 genera are recognized, with some ground sloths found to be bigger, rivaling bull African elephants in size (Friends of Big Bone).

Here in Santa Cruz County, elementary students from the Tara Redwood School discovered a fossil from a Jefferson’s ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii), the youngest and largest of the ground sloth family, and brought it here to the Museum for further research and preservation (SCMNH, 2024). Read more about it: PREHISTORIC SLOTH: PRESENT DAY DISCOVERY

Although remains of both Paramylodon and Megalonyx ground sloths have recently been discovered in Santa Cruz County, it has been found in studies across the Americas that the Paramylodon and Megalonyx rarely occur together in the same faunas (with only ~9% overlap), and when co-occurring, one genus is typically much more common.

At the Rancho La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles, one of the world’s most important fossil collections dating between 45,000 and 14,000 years ago, over 70 Paramylodon individuals have been discovered, including 30 skulls. By comparison, remains of Megalonyx and Nothrotheriops are rare at this site. Another southern California site, the Diamond Valley Lake fossil beds in Riverside County, dating to the same period, has yielded even more Paramylodon fossils, about 280 individuals, making it the fifth most common mammal there after bison, horses, mastodons, and camels (LA County Museum, 1960).

In contrast, studies of woodland-rich regions in the Midwest show an abundance of Megalonyx remains, with Paramylodon appearing only rarely, supporting the idea that different ground sloth species favored different habitats (JIAS, 2012). For this reason, the close proximity of the recent discoveries in Santa Cruz County is particularly notable, offering a rare glimpse of their cohabitation, highlighting the region’s diverse ecosystems.

While the cohabitation of various ground sloths is a rare find across the continent, evidence shows humans of the time were known to interact with these large creatures. Evidence from White Sands National Park in New Mexico reveals that humans interacted with Paramylodon (Science Advances, 2018). Hundreds of trace fossil footprints show sloths and humans moving along a lakeshore, sometimes crossing paths. In one dramatic case, a sloth’s tracks change direction abruptly where human prints overlap, indicating a possible confrontation.

Humans may have occasionally hunted the ground sloths, but climate change and shifting ecosystems likely played the largest role in their extinction. During the wave of megafauna extinctions that also claimed mammoths and saber-toothed cats, 90% of sloth genera became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene (SDZWG, 2025).

Studying fossil specimens like the Paramylodon harlani’s femur is about more than adding rare finds to our collection. The preservation and study of fossils can expand our understanding of the ecosystems in which these creatures lived, how they adapted to changing climates, and what caused them to become extinct. Each bone, footprint, and fossil site is a puzzle piece in the story of life on Earth. By uncovering that story, we not only connect with a lost world of giants but also gain insight into the challenges facing wildlife today.

With the recent discovery of various fossils in Santa Cruz County, we need the support of our community to ensure that our collections can sustainably continue this research. To get involved with fossil preservation and research with us at the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History, please visit our Collections page.

Sloth Showdown: Harlan vs. Jefferson

| Harlan’s Ground Sloth (Paramylodon harlan) | Jefferson’s Ground Sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii) | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Features | Short snout, powerful jaws | Long, narrow snout |

| 3 strong claws per hand, great for digging roots | 3 long, curved claws, great for pulling down branches | |

| ~9–10 ft standing | ~8–10 ft standing | |

| ~2,205–2,400 lbs | ~1,800–2,200 lbs | |

| Bony plates (dermal ossicles) under the skin act as armor | ||

| Diet | Mostly grass & low plants (grazer) | Leaves, twigs, shrubs (browser) |

| Habitat | Open grasslands with water nearby, found mostly in western & southern North America | Woodlands & forest edges, found across most of North America, from Alaska to Florida |