Pins, Process, and Purpose

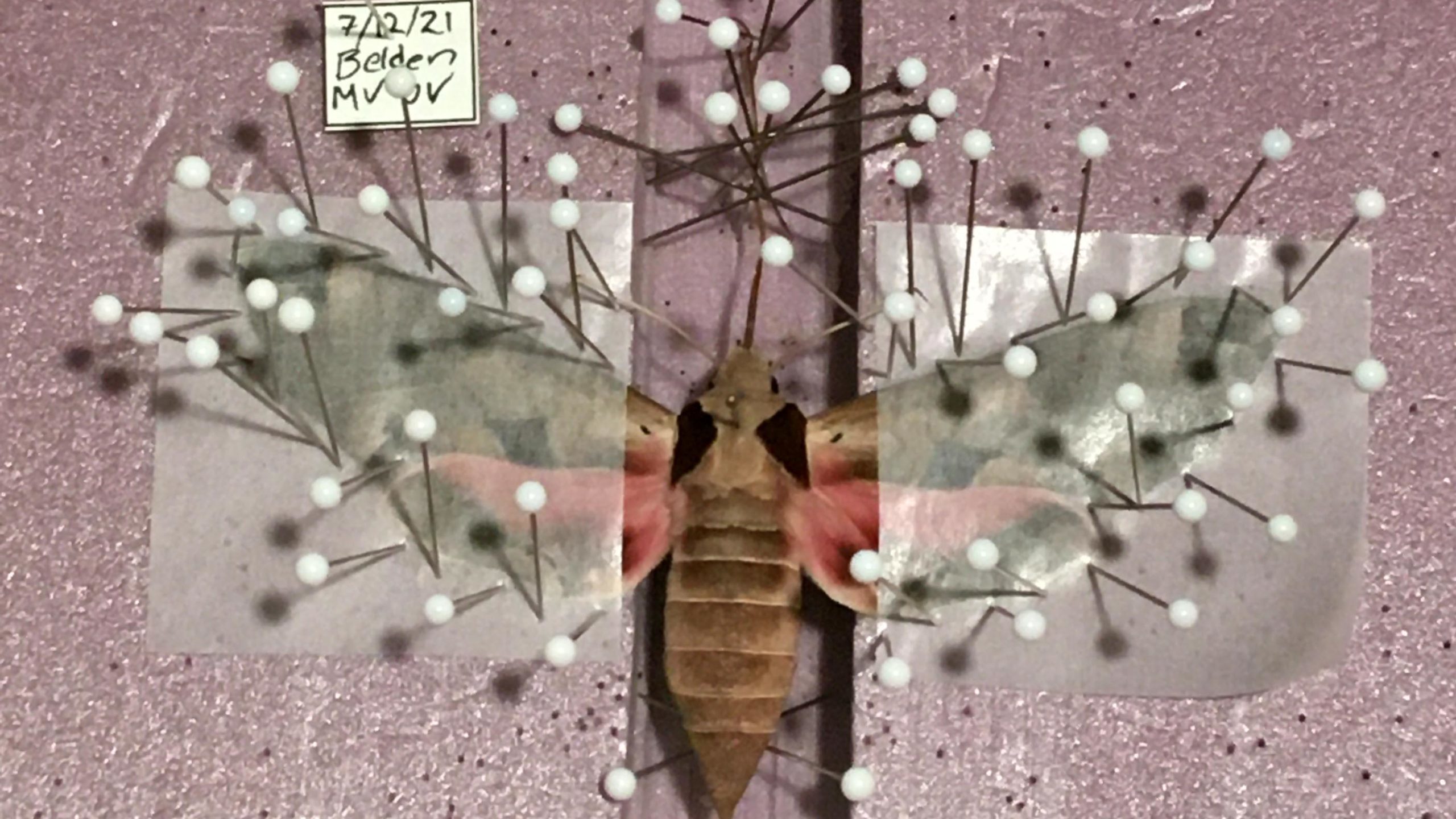

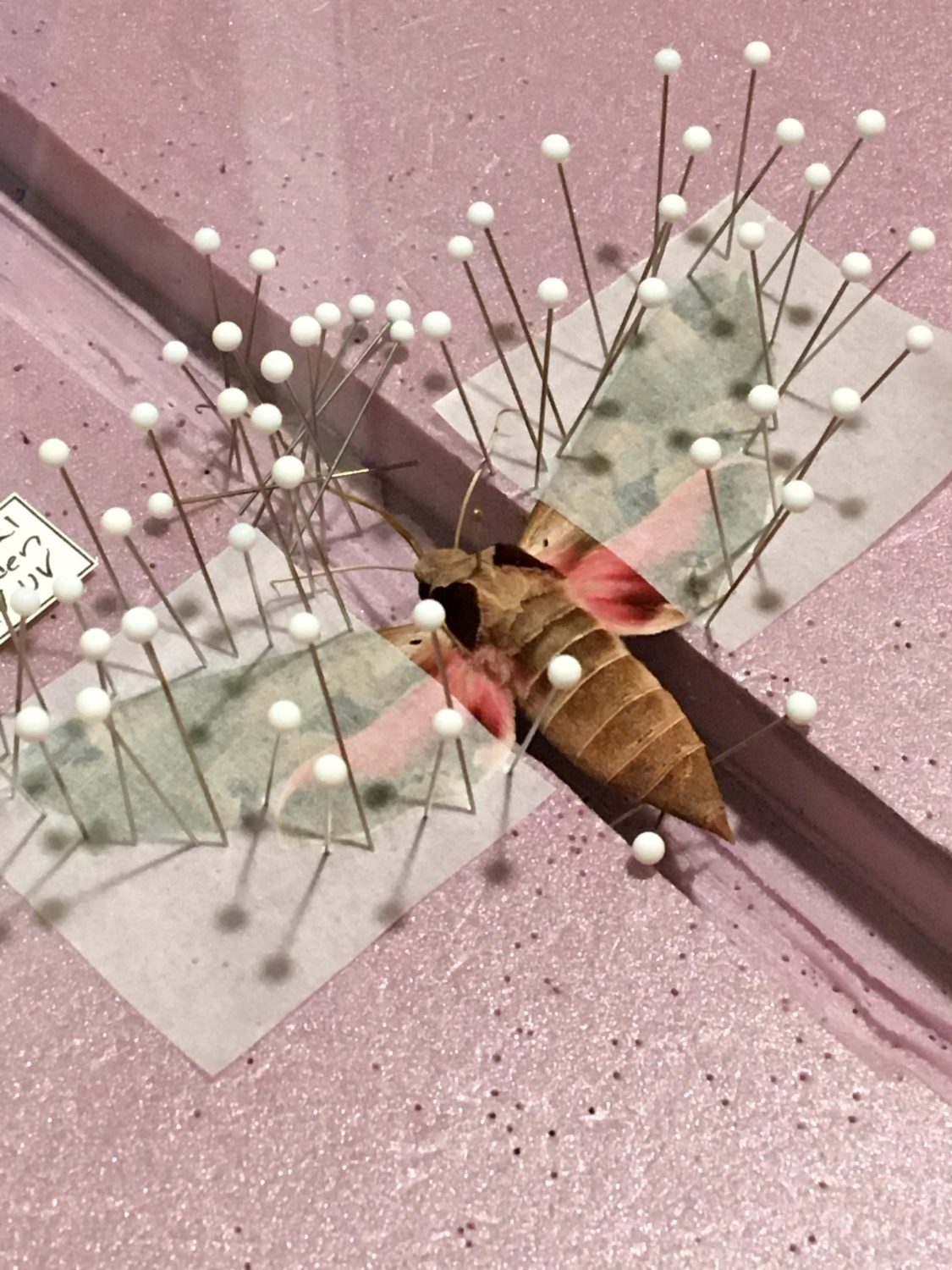

Pressed between pins, glassine paper, and a pinning board rests Eumorpha achemon, the Achemon sphinx moth. Common throughout the United States and findable in Santa Cruz county, this moth was collected by Dustin near Plumas National Forest in July of 2021. Looking more closely, you can see that this moth looks like it was caught with it’s mouth open – pinned out to almost the length of its body is the straw-like proboscis that the animal uses to suck up nectar from flowers.

Achemon sphinx moths are in the family Sphingidae. These distinctive insects are referred to as hummingbird moths, in part because of their large size and hovering flying habits. The family is also known for having the longest reported tongues of any insect – up to almost a foot long! This adaptation helps them feed on flowers with extremely long nectar tubes, making them critical pollinators of a number of plant species.

Even though this kind of coevolutionary relationship between organisms is a common theme of natural history, like in our current exhibit, it is unusual to see a moth on display sticking its tongue out. It is a stylistic choice that helps tell a particular story – but it also makes the specimen more vulnerable. When thinking through specimen preparation choices, Dustin emphasizes the importance of thinking about the “why” of what you’re doing – the overarching motivation for creating and preserving specimens in a collection.

When you’re creating a collection to be used as a source of scientific data, you first want the specimens to be identifiable. In the case of moths like this sphinx, that means spreading the wings and underwings, which are important parts of identification. Above all else, you want them to be survivable – so you tuck in delicate protruding parts like the legs or tongues.

Future researchers who need to look at the rolled up tongue can relax the specimen, using the moisture from water or chemicals to make the specimen more pliable, and stretch it out for observation. For insects whose protruding parts are consistently useful for identification, like the phalluses of certain families of beetles, the part will be removed from the specimen and adhered to a card which is then attached for accessibility on the same pin as the specimen itself.

In this case, Dustin knew about our exhibit and wanted to put together a specimen that shows off this moth’s interesting adaptation. An aquarist by day, Dustin helps care for aquriums including the Museum’s, but he is also enchanted by the world of insects and the stories that they can tell.

“From an environmental studies perspective,” he says, ”as an indicator for what is going on in the world, [entomology] is hard to match. That level of biodiversity and variation, it’s really engaging, it’s a never ending curiosity when you start drilling down into it.” This curiosity helps him stay excited about biology when working with the daily biological responsibilities of animal husbandry.

It’s also a relatively low investment way to contribute to science: “You can create data pretty easily because of the way insects preserve. It’s something that you can sort of come back in and out of, it’s not temperamental, and your specimens can keep for a hundred years if you store them properly.”

Due to his interest in creating more data, Dustin is keen to find locations and species that are not yet well documented, always being sure to get the permission of the landowner prior to collecting. And if those places have historically tended to overlap with music festivals, all the better. The nice thing about coolers is that they can just as easily be used for holding refreshing beverages as they can for preserving insects on the way to the freezer! Once he has time to defrost his specimens, he will pin and tag them to preserve the information that is critical to scientific collections — location, date, habitat, etc. – that tell the fuller tale of the insect.

Sometimes these tales are especially thrilling – On the same collecting trip during which he found this month’s moth, Dustin and his fellow collector Jerry Wilson happened upon a new species of dermestid beetle. Connecting with other collectors is one way to hone one’s entomology knowledge, in addition to using sites like iNaturalist and Bugguide. By submitting good quality images and their best guesses at species identification to Bugguide, Dustin and Jerry caught the attention of a moderator who put them in touch with a leading professional entomologist who was able to create the formal novel species description.