Guide to the Swift Street Outcrop

By Graham Edwards and Gavin Piccione (aka the Geology Gents)

Santa Cruz is an ideal place to explore marine and coastal geology, with millions of years worth of geologic history exposed along its sea cliffs. One of the Gent’s favorite outcrops in Santa Cruz is along the cliff face on West Cliff Drive, at the end of Swift Street.

Getting to the outcrop

Park at the end of Swift Street and cross West Cliff Drive. Take one of the paths through the ice plant and walk down onto the coastal platform. Be careful, in some areas the path down to the outcrop can be steep.

To find the Swift outcrop on a map, the latitude and longitude are:

36˚56’58.72” N

122˚02’49.22” W

Download our West Cliff Rock Walk guide to help you get there!

A guide to the rock formations

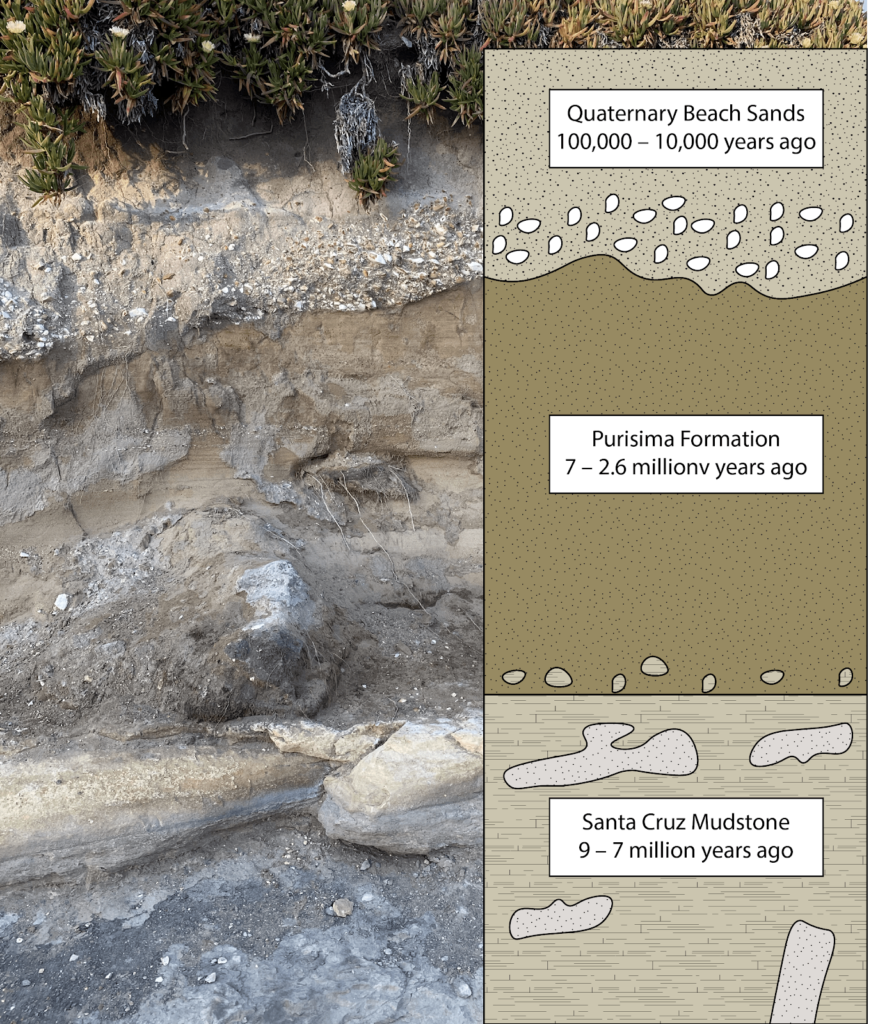

The Swift Street outcrop contains over 9 million years worth of geologic history of the coast of Santa Cruz. Familiar formations found at Swift Street include the Purisima sandstone and the Santa Cruz mudstone, along with younger beach deposits that make up the top layer of the outcrop (pictured). Each of these layers arre separated by sharp erosional contacts (geologists call these disconformities) that represent missing time and material in the rock record.

Watch to learn more: Santa Cruz Formations

Ancient Methane seeps within the Santa Cruz mudstone

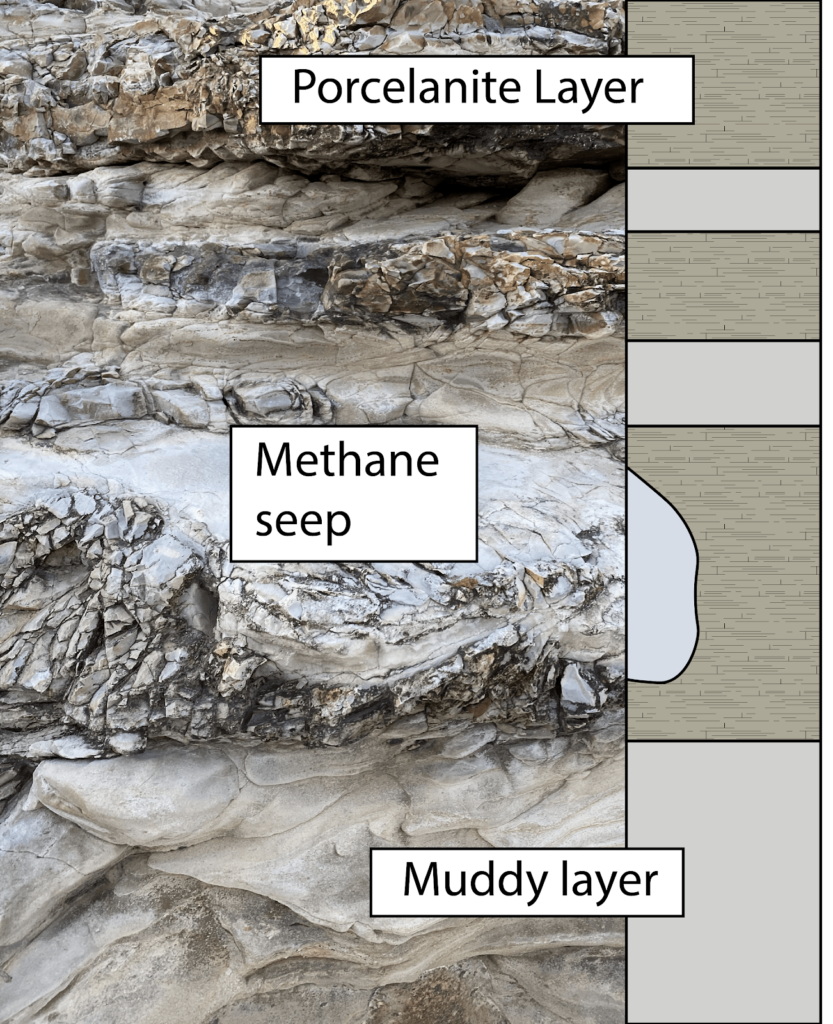

The bulbous, light-colored features found at and near the Swift Street outcrop are the geologic remnants of methane seeps, also known as “cold seeps”.

These formed while the Santa Cruz Mudstone was still mud in deep waters off the coast of California between 7-9 million years ago. The rock accumulated as sediments, including the bodies of perished sea critters, fell to the sea floor. As the bodies of phytoplankton and other marine microorganisms decayed in this mud, they released gases that slowly worked their way up to the surface. As these gasses followed cracks in the firmly packed sediment, they gradually widened these conduits and cemented the walls with carbonate minerals (the same thing limestone, chalk, and marble are made of), creating a sort of chimney to release these gases and fluids out of the seafloor.

Seeps like these that bring methane gas and fluids from deep below the seafloor can be found today out in the deep regions of Monterey Bay. In millions of years from now, these same chimneys may find themselves on a new coastal outcrop!

Seafloor methane seeps like the ones preserved at Swift Street occur in the Monterey Submarine Canyon today, providing nutrients for mini ecosystems on the seafloor.

Layers of the Santa Cruz Mudstone

While the fossilized cold seeps tend to get a lot of the attention, the tough Santa Cruz Mudstone around them is itself a fascinating piece of rock. In this area, the Santa Cruz Mudstone hosts alternating layers of pale mud and blocky porcellanite (pictured right), a rock that gets its name from its close resemblance to unglazed porcelain. This rock is very similar to chert, a glassy rock formed at the seafloor from the accumulation of the glassy skeletons of diatoms. Porcellanite, like that found at the Swift Street outcrop, has a bit more clay and calcite (probably from critters that make chalky skeletons) giving it its more porcelain-like appearance.

The layers of porcellanites have a distinctively blocky texture. This results from the very brittle nature of the rock type. Just like pieces of porcelain, when these were squeezed and warped by tectonic pressure, rather than bending like the softer, more ductile mud layers, the porcellanite essentially shattered in response to those forces. Yet, even in its shattered state, the porcelanite rock is remarkably strong and durable. For this reason, Santa Cruz Mudstone with its rugged porcellanite layers makes up many of the flat bases of the sea cliffs around West Cliff as it stands up against the erosive force of the waves that more easily cuts into the sands and sandstones of the overlying cliffs.

The chunks of porcellanite just above the contact tell the story of the earliest history of the Purisima Formation as powerful waves broke down and churned up rocks that were incorporated into the first layers of the Purisima sands.

The Purisima Sandstone Formation

Above the Santa Cruz mudstone lies the Purisima sandstone, a rock formation known throughout Santa Cruz for its abundance of stark white fossils of ancient shells. Swift Street contains only a relatively small section of the Purisima Formation, but several areas within it exhibit amazing sedimentary textures. Up on the cliff, sections of the Purisima are a flat brown, with no visible fossils, and parallel “beds” or ancient sediment layers (pictured). These areas represent long periods of constant sediment deposition, with no major storms or changes to the environment.

Elsewhere in the outcrop, shell-rich layers and features called “cross-beds” tell us that at other times between 7 and 2.6Ma, this area experienced large storms that created strong ocean currents. The jagged contact between the Purisima formation and the above Quaternary-aged sediments represents nearly two million years of lost time in the rock record.

Erosion and deposition of sands on top in the last 100,000 years

The base of the uppermost layer of the Swift Street outcrop is made up of an unconsolidated matrix of fine sand surrounding large, cobble-sized pieces of the underlying sedimentary rocks, as well as abundant shell fragments. Because this layer is made up of fairly loose sediments, as opposed to rock, we know that it has not experienced long periods of burial required to turn sediment into rock (or lithification in geologist jargon.) For large cobbles to be ripped-up from the underlying layers and deposited here, requires high-energy wave systems like those found on the modern coast. Therefore, the transition from the underlying Purisima sandstone to these sediments likely represents a time where the Santa Cruz coast shifted from deep water to a coastal zone, likely as a result of sea level fall and tectonic uplift.