June 10 – August 20, 2023

Seashells hold secrets from an underwater world. These tiny treasures connect us with the vast ocean and the hidden creatures that live within them. Humans have long been captivated by their diverse colors and intricate forms, but our actions also threaten their future.

What is a Mollusk?

The phylum Mollusca is diverse and abundant, with over 100,000 known species living both underwater and on land. Soft-bodied and spineless, mollusks vary greatly in appearance and include snails, slugs, chitons, bivalves, and cephalopods. This diverse group includes animals that play many roles – grazers, predators, scavengers, and even filter-feeders that clean the water.

While many mollusks have external shells, those of cephalopods like squid and cuttlefish are internal. Chitons produce several shell plates — sometimes externally and sometimes internally. Slugs don’t have any shells at all!

Shell Science

Hard Outside, Soft Inside

Shells are primarily made from calcium carbonate, a strong substance that helps to protect the animal’s soft body. Shells grow with the animal inside. Over time, protein and minerals are excreted from the mantle (soft tissue), forming new layers of shell from the inside out.

Dissolving Shells

The ocean absorbs some of the excess carbon dioxide we emit into the atmosphere when we burn fossil fuels, which leads to “ocean acidification.” This slows shell growth and dissolves calcium carbonate, putting the animal inside at risk.

Rich Research

Museum collections with robust data can be important tools for study. Scientists are actively researching fossil shells from this museum’s collections. Museum collections can also highlight changes in populations over time.

The Enduring Life of a Shell

Many shells play a role in an ecosystem after the animal inside is gone. Empty shells can become homes for other animals, such as hermit crabs, and over time shells break down and become the sand beneath your feet at the beach.

Museum Malacology Collections

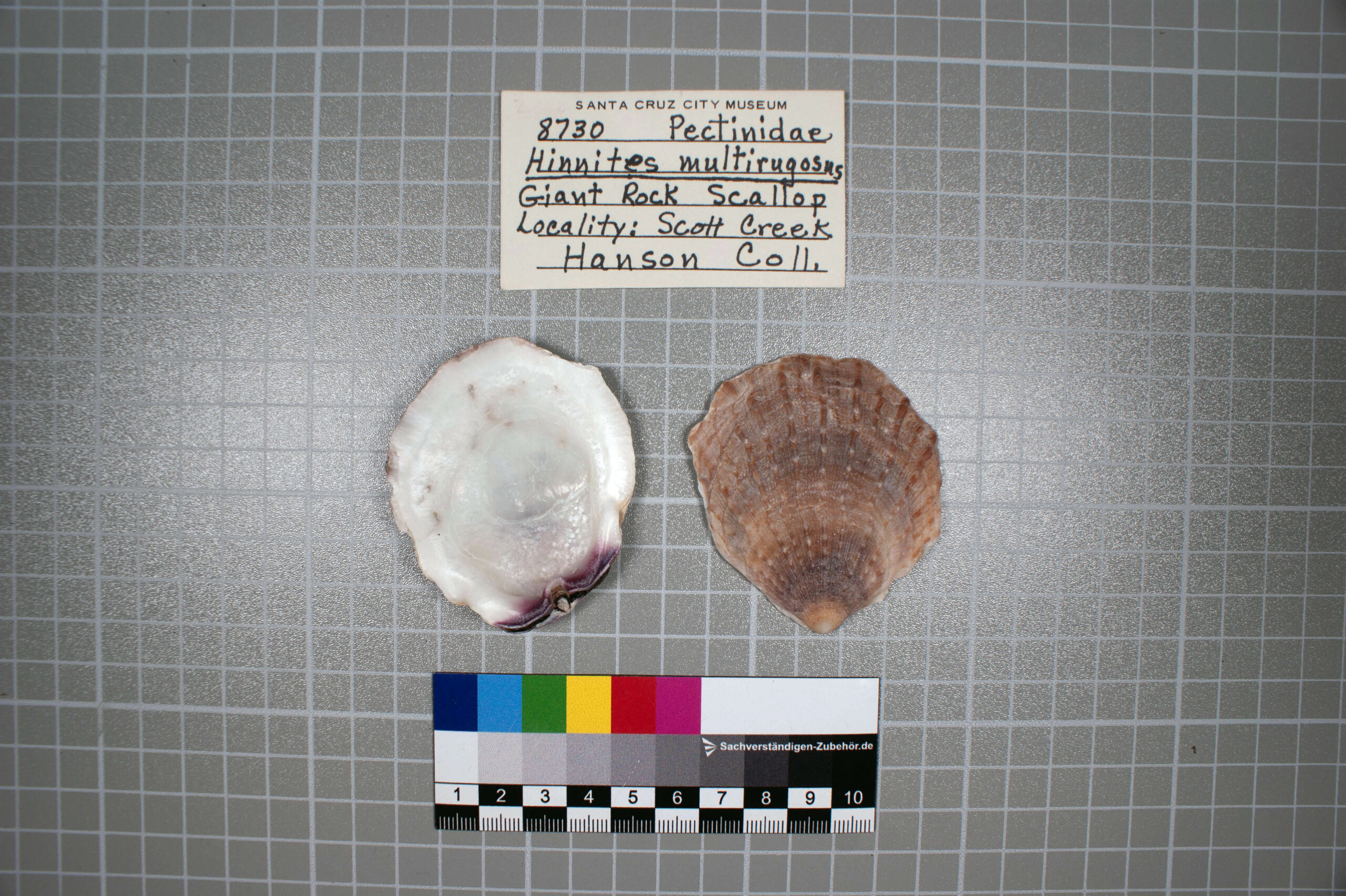

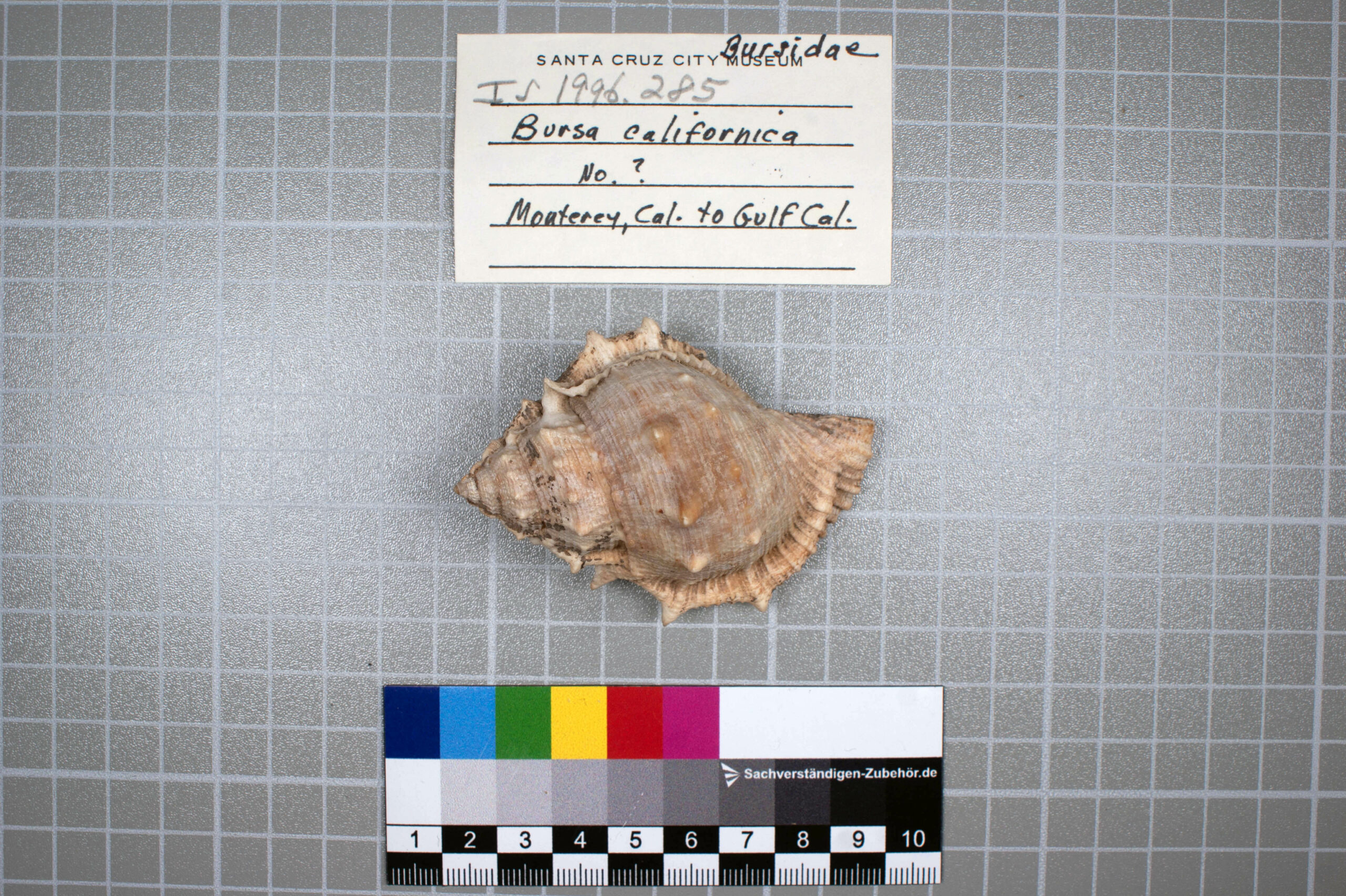

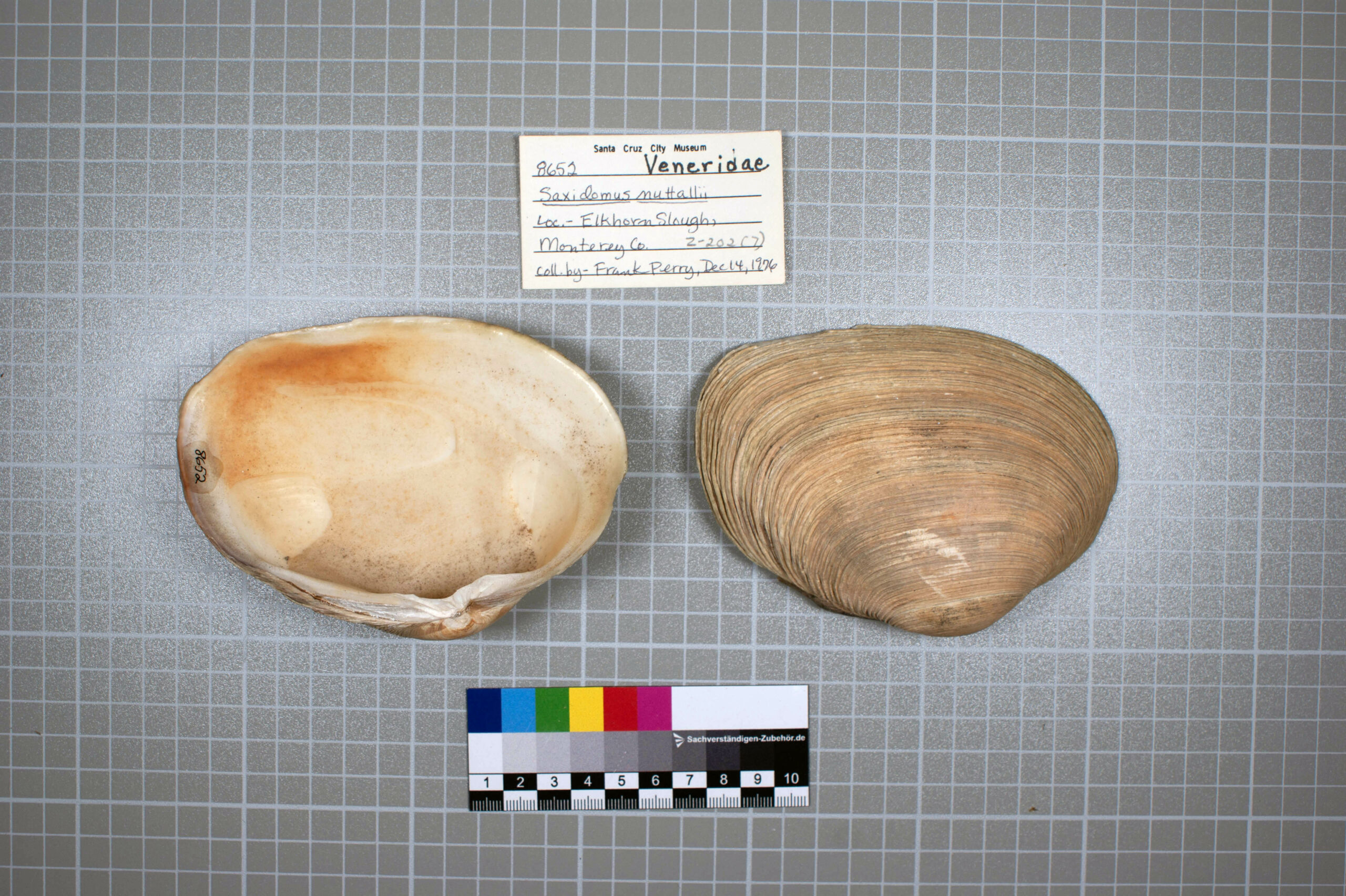

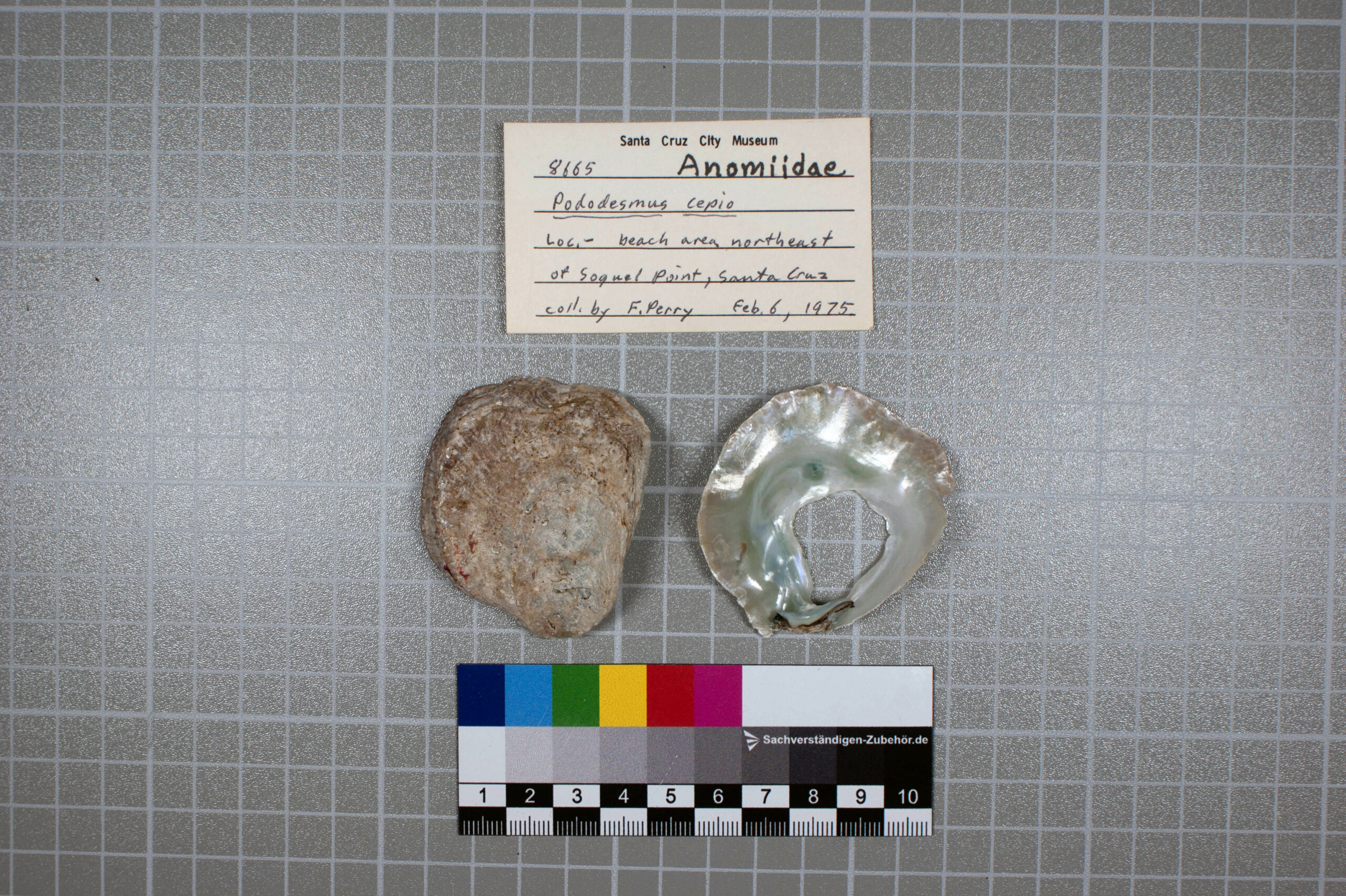

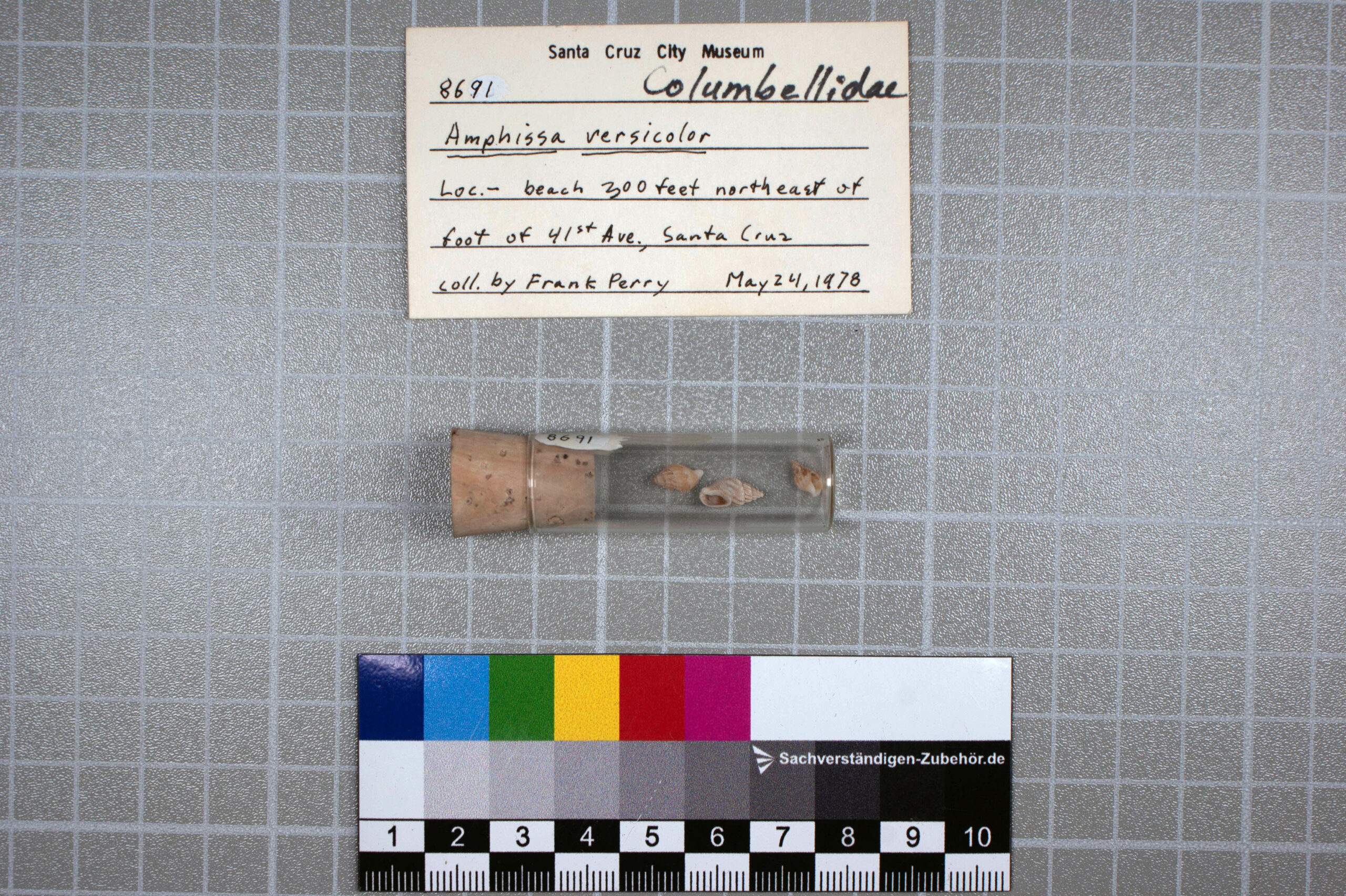

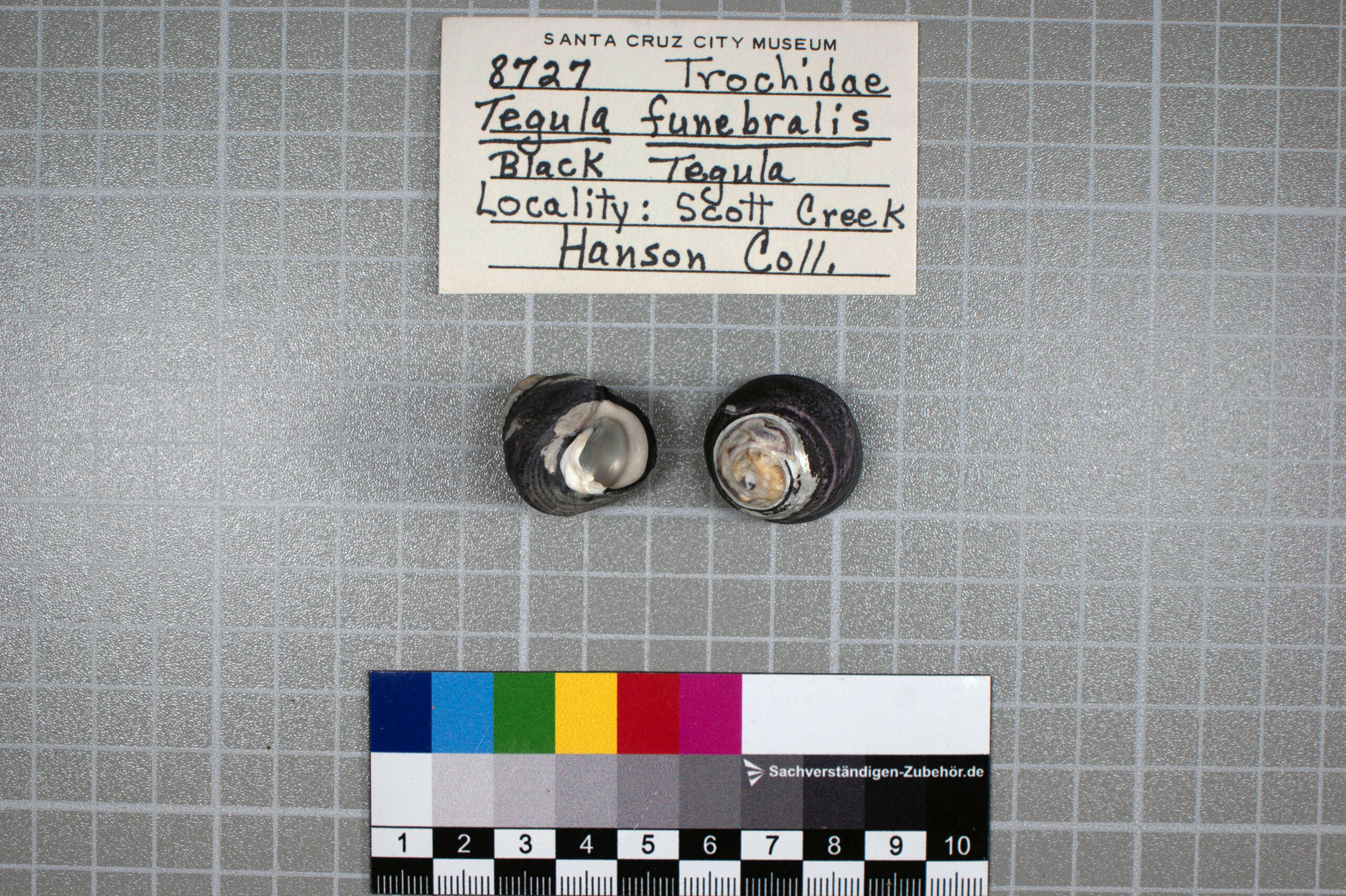

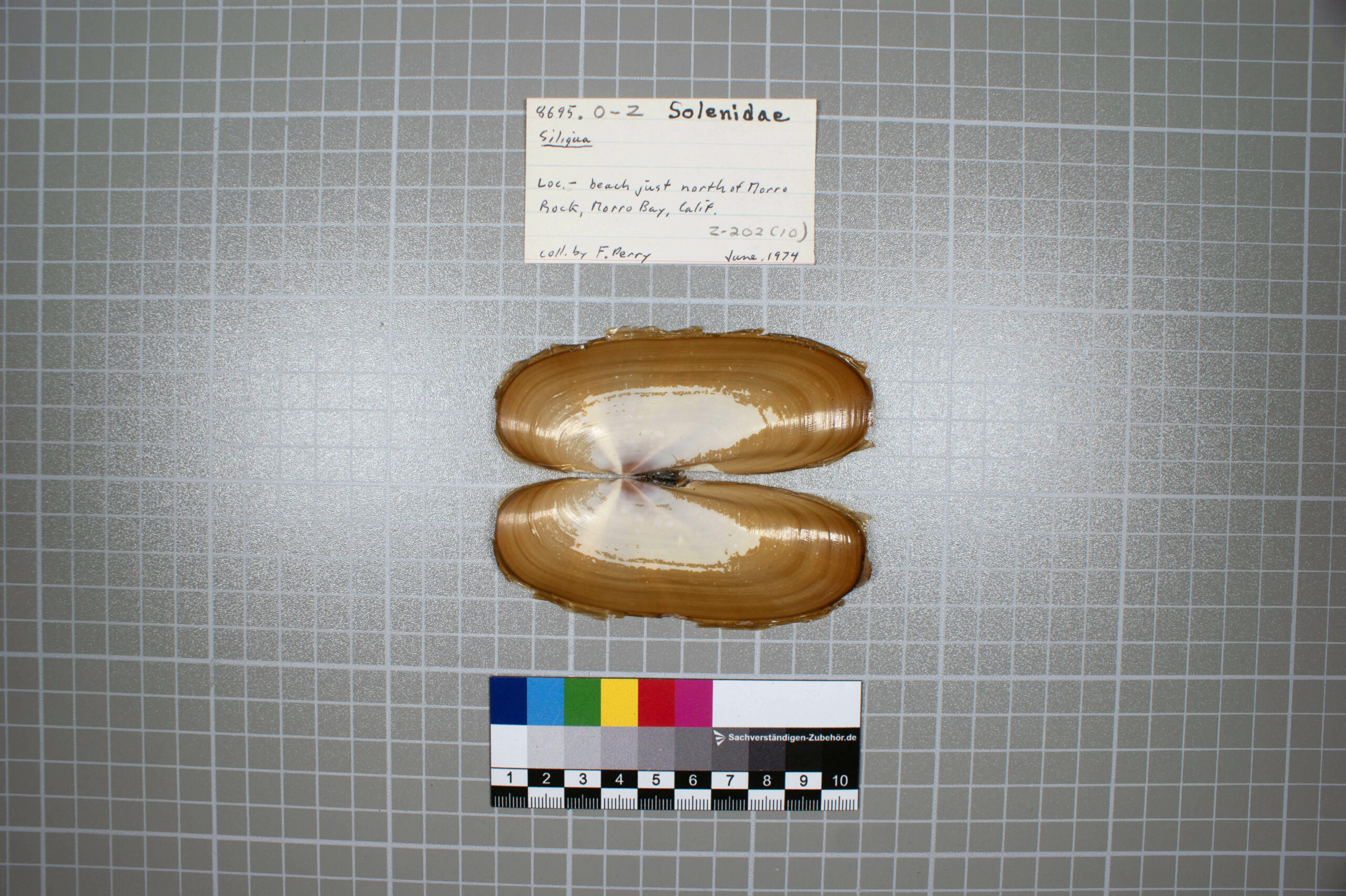

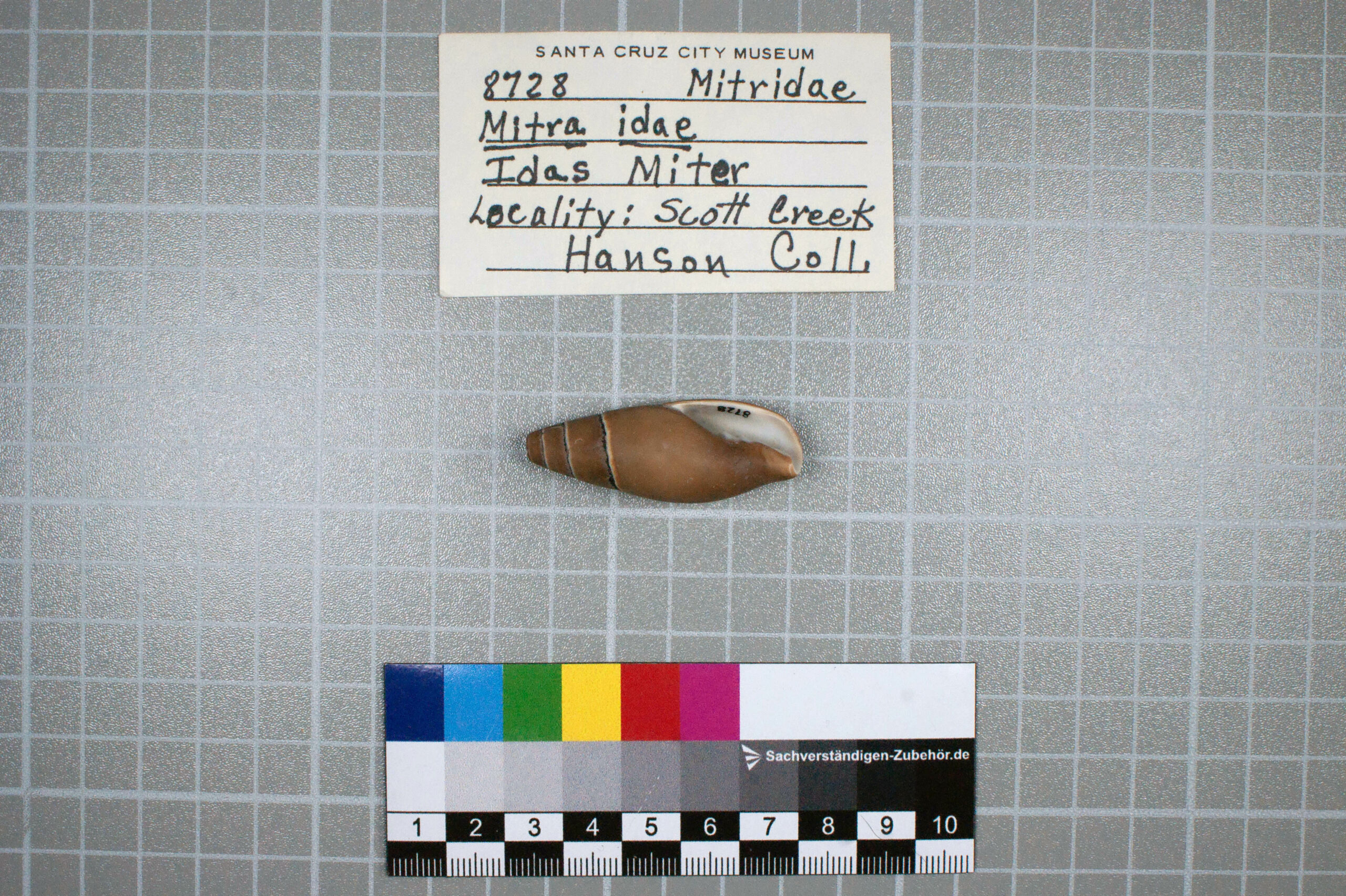

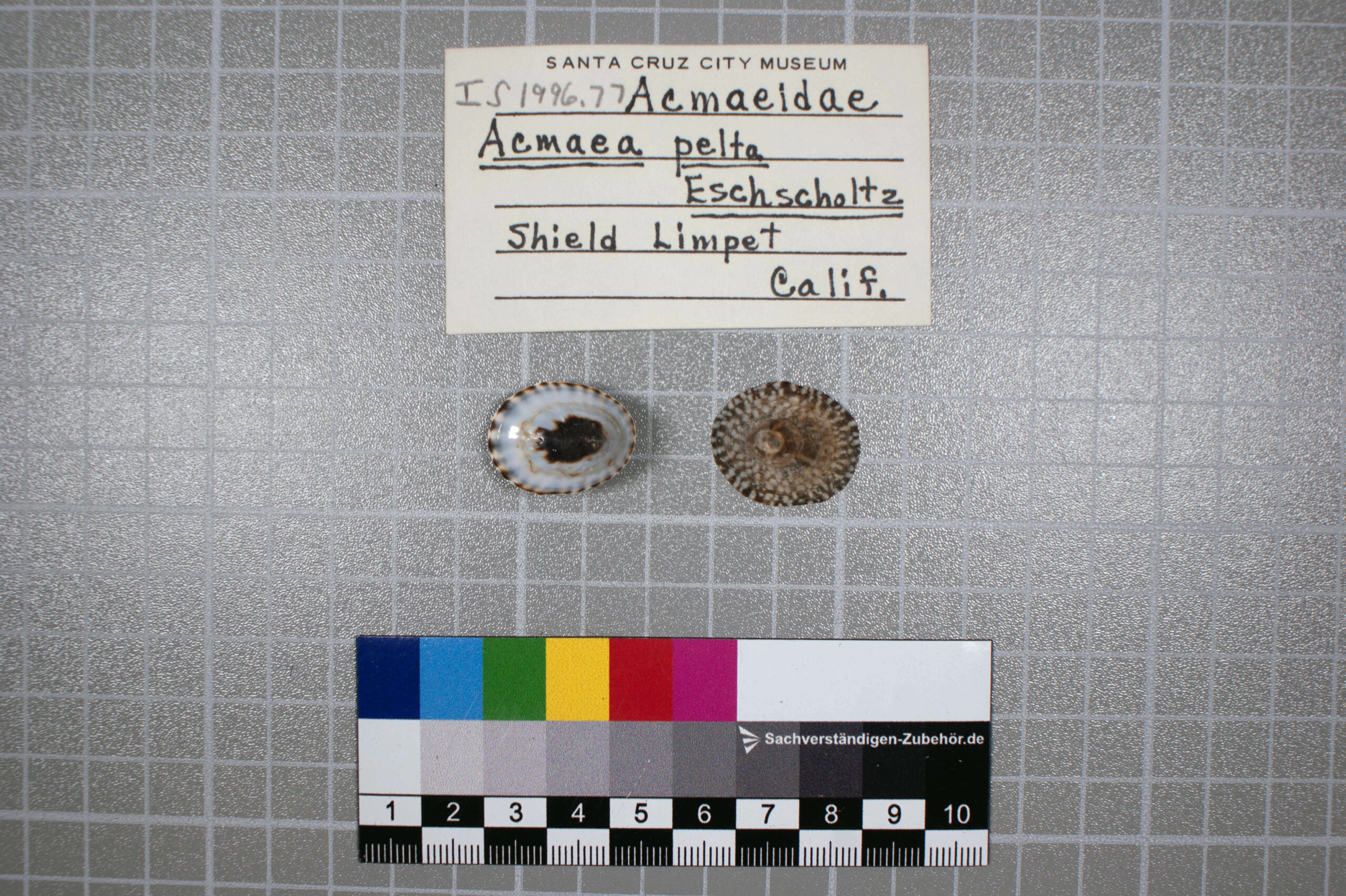

Here’s a sample of specimens currently being digitized by collections staff. You might notice the names are different on the captions versus in the picture – this is because digitization isn’t just about photographing specimens, it’s also about confirming up-to-date taxonomy in an evolving world of science. Collections staff have updated the database records for these specimens to reflect accurate names, while preserving the historic ones.

Shells for Future Generations

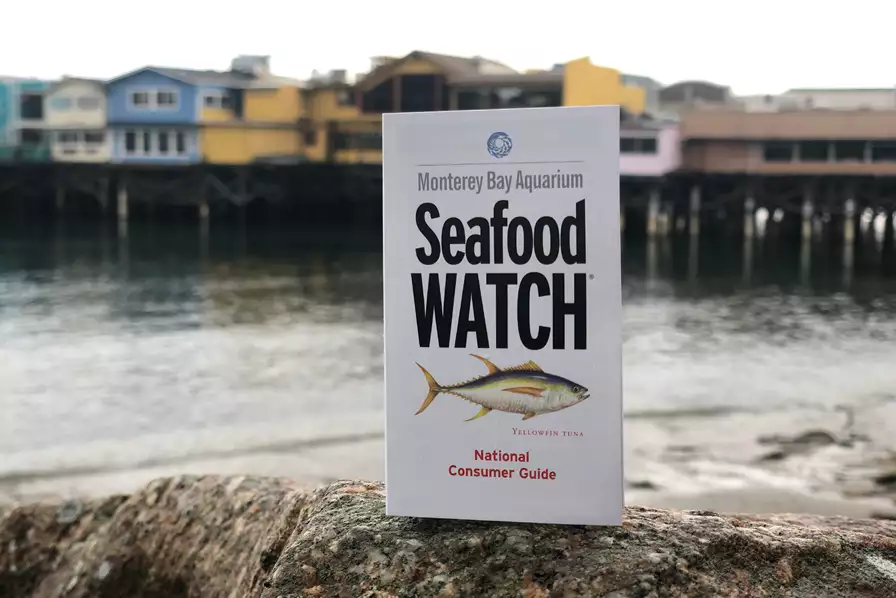

Shells and the animals inside of them have long attracted our attention, but overfishing, habitat destruction, and climate change can collapse ecosystems and devastate entire industries. These ocean stewards are protecting marine ecosystems so that future generations can enjoy the beauty of seashells and the benefits of a healthy ocean.

Indigenous Connections

Nowadays we are not allowed to gather abalone because the oceans are polluted and the abalone are dying off. I now get my abalone from people who already have it. With climate change the balance of the ocean is affecting all of Mother Earth. We must change our ways and clean her up and help protect her so we can bring back the abalone and other sea animals again.

-Eleanor Castro, Amah Mutsun Tribal Band

Olive snail, clam, and abalone have long been important for Indigenous cultures along the Central Coast of present-day California and beyond. A widely traded resource, these shells have long been used as currency and in beadwork that adorn baskets and jewelry.

(Right) Abalone pendants collected in Santa Cruz prior to 1900, Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History Collection.

She Studies Seashells

Collecting shells, studying them, and making art with them, was historically an acceptable way for women to engage with science and nature. In 1905, this Museum was founded upon a collection of shells from lighthouse keeper Laura Hecox.

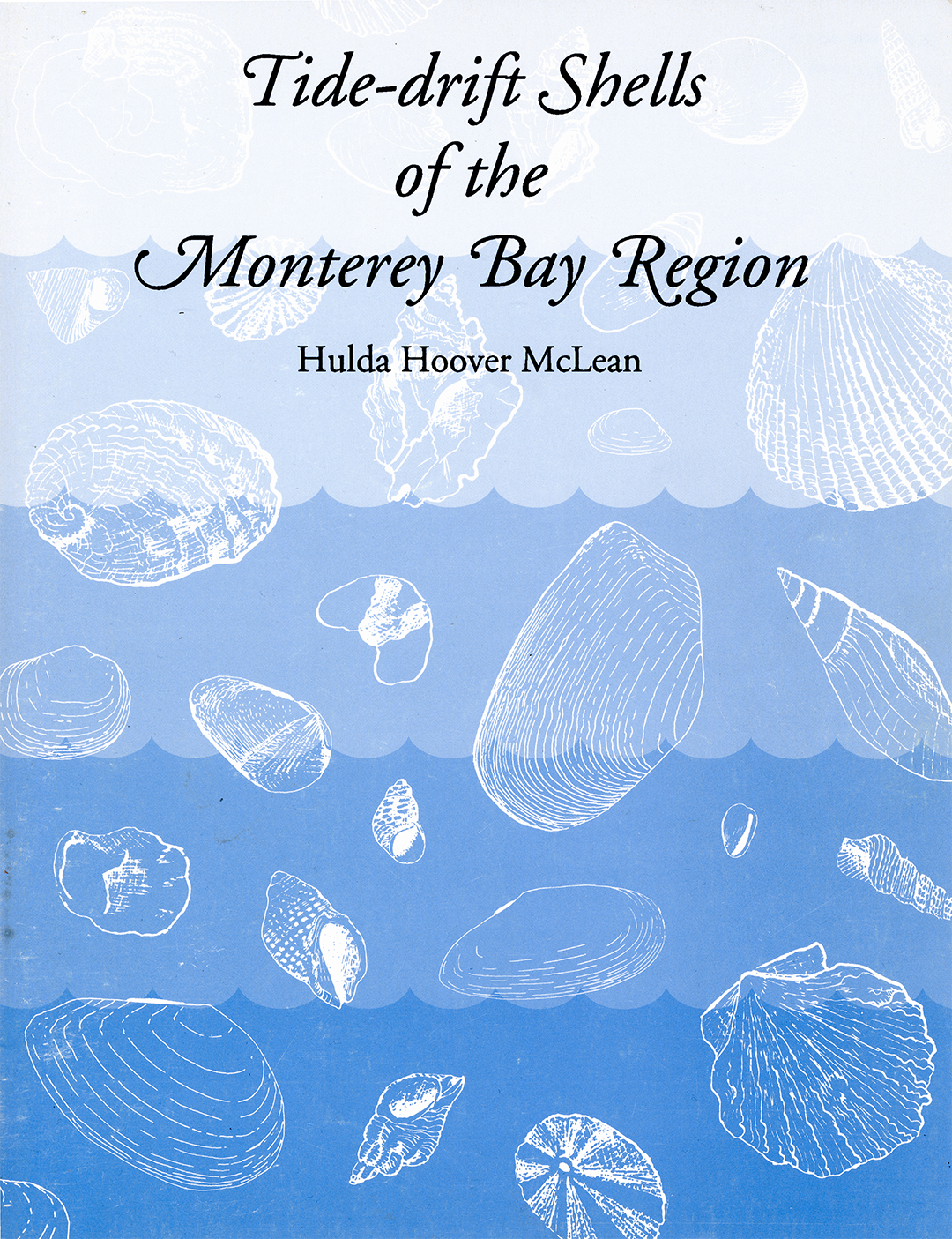

Laura’s collection paved the way for local naturalist Hulda Hoover McLean to write her book Tide Drift Shells of the Monterey Bay. Published in 1975, her book extolled the virtues of shell collecting, while acknowledging that many of the shells she observed as a child were no longer present.

Even if there are no collectible shells, a walk along the tide drift will yield recognizable bits and pieces of fifteen to twenty species. Don’t spurn them. Half the joy in collecting is in the learning process; these imperfect pieces are valuable starters – studying them will enable us to recognize and identify the perfect specimen when we finally find it. Shells, like gold, are where you find them.

-Hulda Hoover McLean