Late rain and sporadic sunshine are lighting up the local landscape with green growth and bright blooms, raising spirits for the oncoming spring. This month’s Close-Up highlights a slightly less vivid but no less delightful collection of plants – a collection of preserved grasses, complete with identifications by their collector, beloved naturalist and conservationist Randy Morgan.

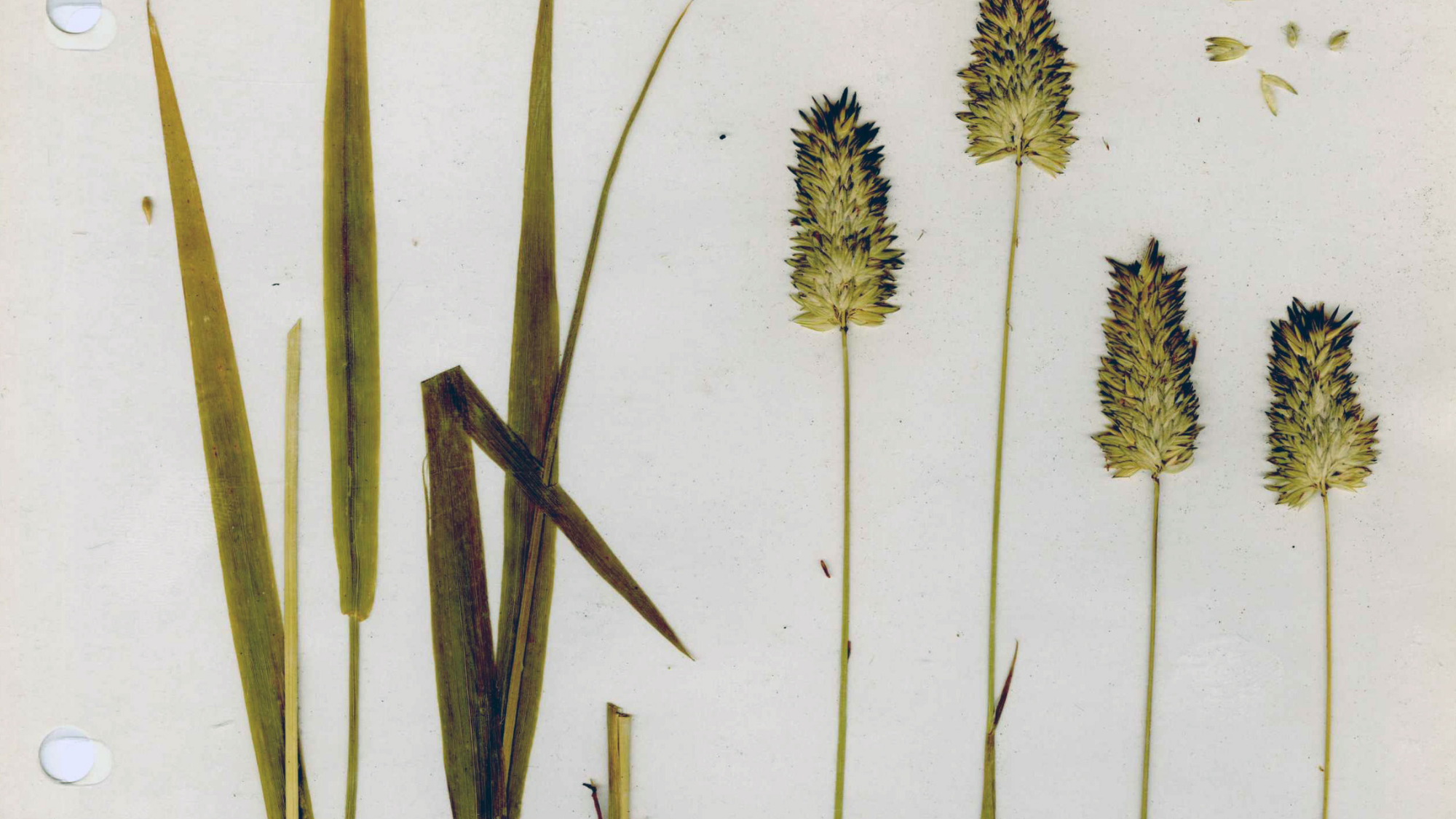

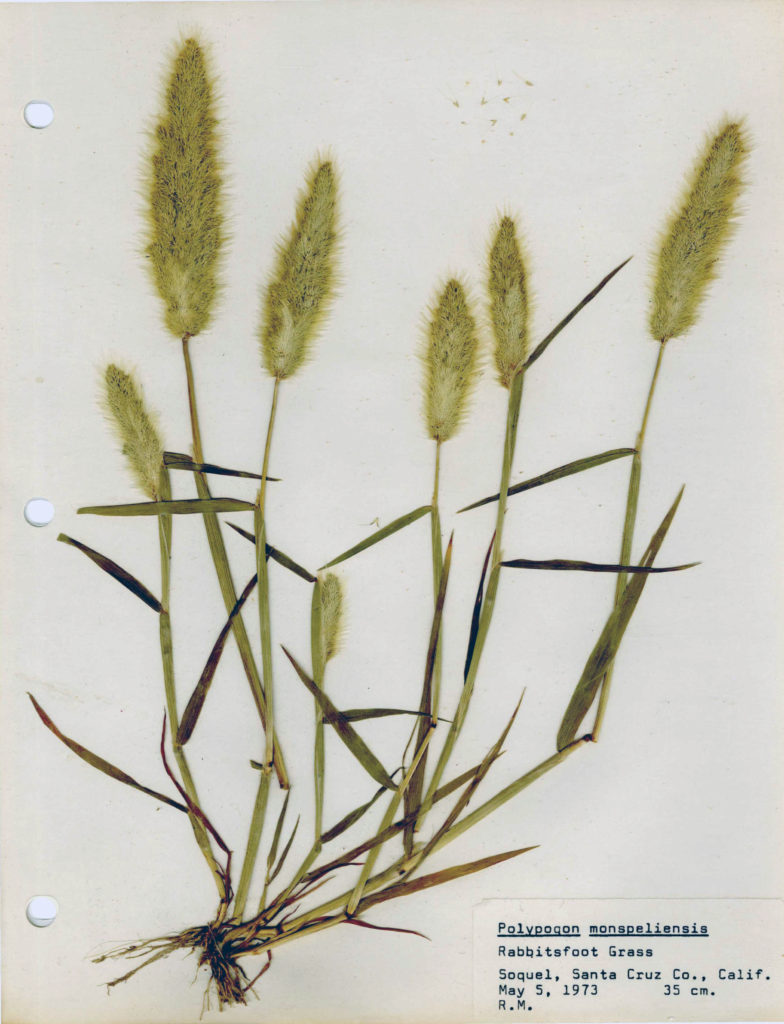

At first glance, the graceful blades and intricate flowers are captivating for their beauty alone, as in specimens like this California Canary grass (Phalaris californica). After all, another specimen in this collection represents a plant that so charmed Californias that it was designated the state grass. Not only are they beautiful, they’re informative – each specimen is carefully arranged to make visible important features such as the roots, blades, and flowers. The subtle distinctions between grass species in a field might blend together, but laid out on the herbarium sheet (or for that matter, conveyed via botanical illustration) the various parts of the plants can be easier to see.

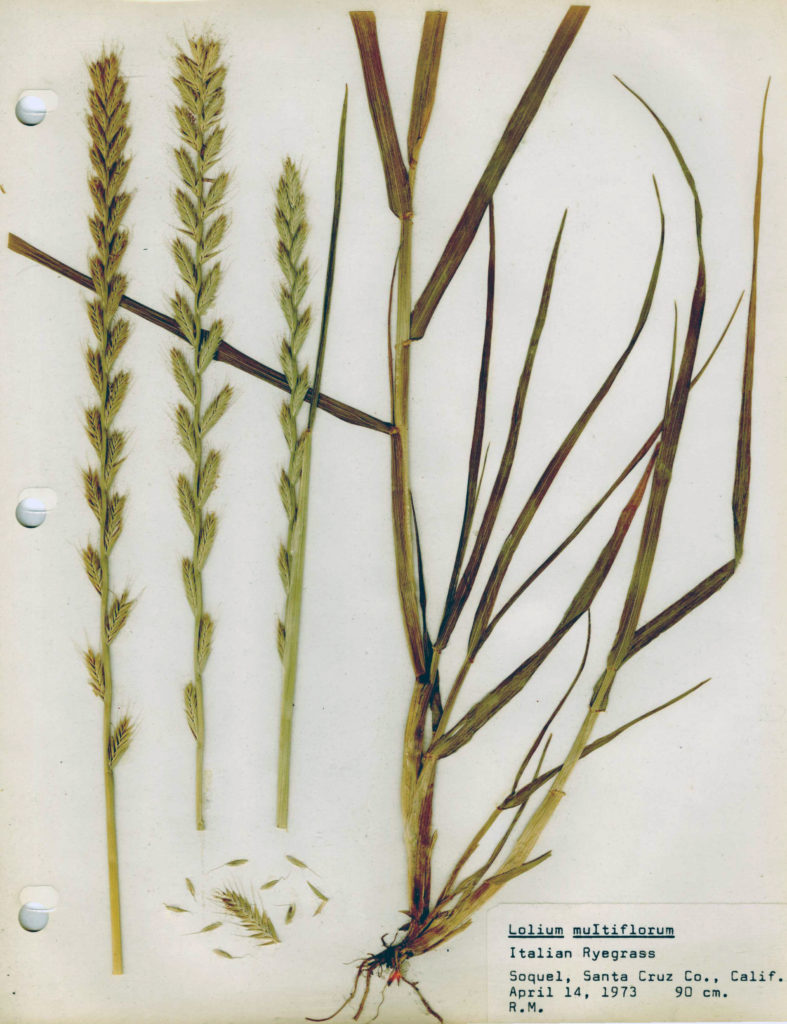

This arrangement of significant features is a critical component of a quality herbarium specimen. The scientists who use herbaria (the plural of herbarium, or collections of plants preserved and labeled for reference, a practice which is more than 700 years old) such as these need to be able to see as many diagnostic features and as much of the plant as possible for use in understanding the identities of specimens, their classification, and their relationships to one another. This is harder with some plants than others – while grasses aren’t as difficult to capture on the herbarium sheet as, say, rattan palms, – at 103 cm, the above specimen didn’t quite fit on the herbarium sheet. Although this sheet is a petite 8.5 by 11 inches, at 103 cm this specimen still wouldn’t have been close to fitting on today’s standard herbarium sheets of 11 by 16 inches.

Thankfully, Morgan noted the height of the specimen on the label. The more than seventy specimens also have, at least, the general location name of where they were collected, their common name, scientific name, and collector listed. Quality herbarium specimens are fixed to archival paper and accompanied by labels that include this key information. It is preferable to have any other associated information like collection number or i.d., description of the plant and any collecting notes. Specimens in herbaria that meet these qualifications are called voucher specimens.

Not only is this information important for science, it’s important for collections management as well. As we strive to enhance the accessibility of our collections, the level of data a specimen or set of specimens has helps us make decisions about what to prioritize for the time-consuming process of digitization. The time spent is well worth it – the enormous increase in access to specimens brought on by digitization has not only accelerated the current possibilities of plant science but also created new opportunities for how we think about pressing issues like the future of botanical biodiversity.

Of course, digitization efforts connect us to more than just the scientific value of pressed plants. Who can be surprised, when herbarium specimens readily embody the intersection of science and art cherished by nature enthusiasts everywhere. One such fan was the poet Emily Dickson, whose enchanting collection of preserved flora, collected during a period when the formal study of science was inaccessible to many women, can now be accessed by anyone with an internet connection.

This collection of grasses is also dear to us for a different kind of connection – that of our institution’s relationship with Randall Morgan. Often known as Randy or R, Morgan was a pillar of the local natural history community. And though he passed away a few years ago, his influence on the natural world and those who celebrate it in Santa Cruz is evident from the the Sandhills that his activism helped to save, to the local chapter of the California Native Plant Society that he helped found, to this very Museum where he worked as a taxidermist to pay for studying linguistics at UC Santa Cruz.

UCSC’s Norris Center for Natural History, the primary steward of Morgan’s collections, details in their vivid biographical rundown, Morgan’s love of nature began with birds and buoyed him through his life as a largely self taught naturalist. Even without formal training, his passionate observation of the world around led him to many achievements, including the discovery of new species, and his collection of plant voucher specimens that serves as the foundation of our understanding of plant biodiversity in the Santa Cruz Mountains. His story is inspiring in part because, like so many of those featured in the Norris Center-led exhibit Santa Cruz County Naturalists, it expands the notion of who can be a naturalist.

It’s inspiring to have this collection then, as a snapshot of the plant communities of California in the 1970s, but also as a window into Morgan’s dedicated observations of the natural world. As the Norris Center director Chris Lay mentions in the CNPS’s Randall Morgan memorial “When I look at plants I’ll be very satisfied if I can just tell you the species name. But Randy, he recognizes the diversity within the construct we call a species.”

For a deeper dive into the legacy of collector Randall Morgan, keep an eye on our April calendar for our next Collections Close-Up event.