This December’s Collections Close Up features a familiar face, rather, fossil. We’re highlighting a whale ear bone that lives in our permanent fossil exhibit, currently under wraps for the final month of our Sense of Scale exhibit about earthquakes, Loma Prieta, and seismologist Charles Richter. In doing so we are also able to explore the locale from which this fossil was uncovered through a virtual field experience of the Purisima Formation.

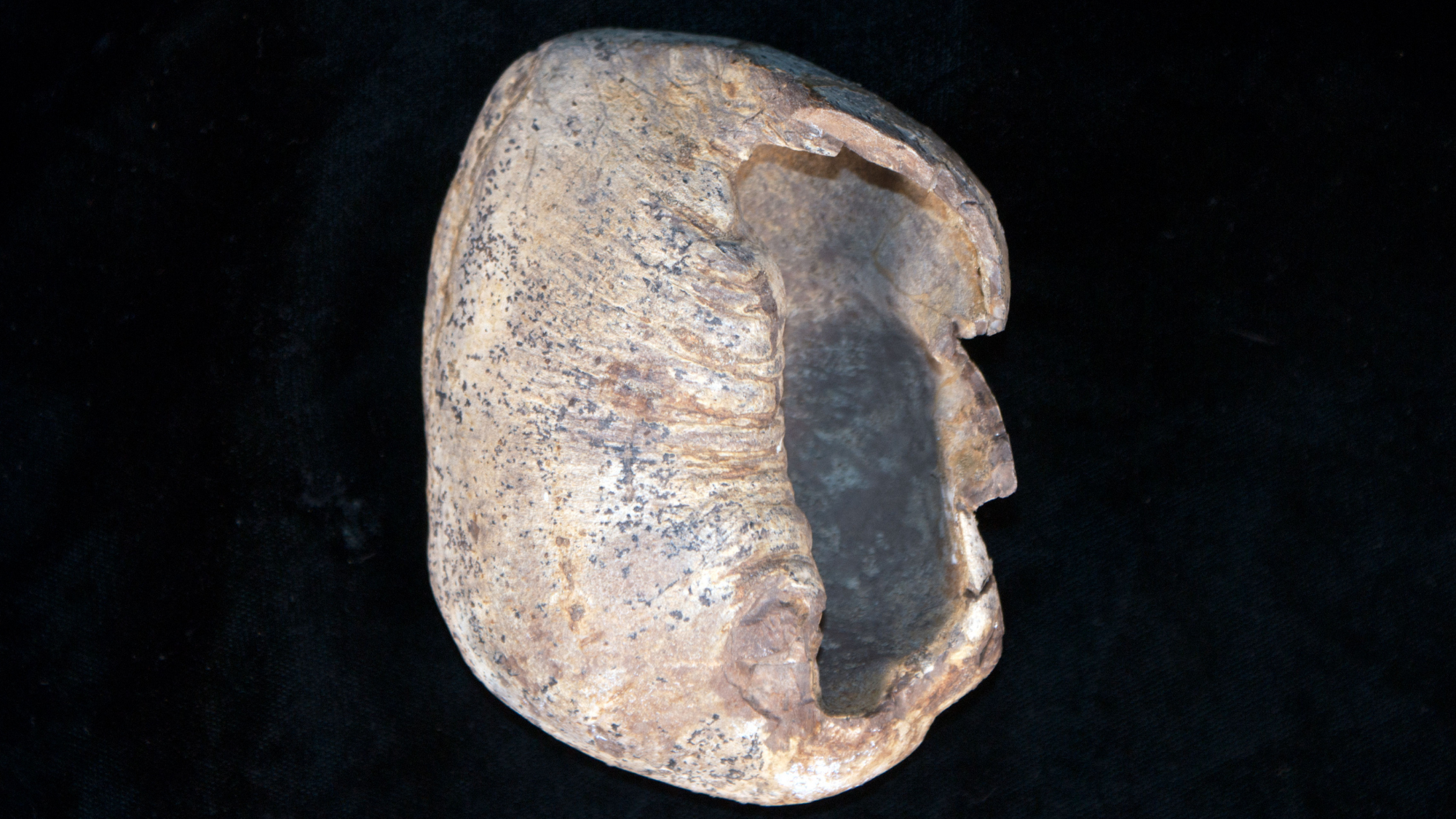

About the size of an oblong, to the casual observer this specimen might look like a cross between a seashell and a shriveled nut. It is in fact the ear bone of an ancient whale of unknown species. More specifically, it is a tympanic or auditory bulla, a bony capsule enclosing and protecting delicate parts of the middle ear.

In humans, sound waves are funneled through the fleshy outer ear down the ear canal to the eardrum, where this bony protection is part of the temporal bone of the skull. This system works well in the air, but as anyone who has gone swimming knows, not so well in water. Part of the reason sound comes out garbled is because of the connection of the ear bones – your skull and your eardrums are all vibrating in response to sound waves at the same time, rather than in sequence, making it difficult to pinpoint the garbled sound’s origin.

For cetaceans, the category of marine mammals that includes dolphins and porpoises, that just couldn’t cut it. These creatures evolved about 50 million years ago from a terrestrial mammal that looked something like a small hippopotamus. When it comes to life in the water, sound is a much more effective sense than light for communication, hunting, and finding your way. They have no external ear openings, and instead of sound waves traveling through an ear canal, they rely on pads of fat in their jaws to amplify vibrations from the water.

For a more in depth discussion of fossil whale ear bones, check out the Virginia Museum of Natural History’s paleontology blog. This article describes just one example of how scientists can learn a ton from this relatively small bone found in large creatures. In addition to shedding light on the ancient ancestors of whales, the study of these bones can illuminate how it came about that toothed whales hear best at high frequency ranges while baleen whales hear best at low frequency ranges, how it may be the case that some whales hear well at both, and more.

Our fossil was found in 1973, embedded in a chunk of Purisima Formation exposed along the Capitola Coast dating between 3 to 7 million years old. In general, museums and paleontologists are careful about how we track and provide access to information on where fossils are found in order to help preserve as much scientific information as possible while also protecting fossil discovery sites for science and the public. At the same time, this caution is balanced with a commitment to educate and share information about these same discoveries. An exciting example of educational outreach featuring the same general area where this ear bone was found is the Eastern Pacific Invertebrate Communities of the Cenozoic partnership’s Virtual Field Experiences initiative.

These virtual field experiences are richly immersive presentations of text, image, and video that serve as online excursions to different classic paleontological sites. So far there are two VFE’s, with more on the way. The first focused on the Kettleman Hills on the western edge of the central valley, Fortunately for us, the second focuses on two areas on the central coast where the Purisima formation can easily be observed – at Moss Beach in San Mateo County and at Capitola Beach here in Santa Cruz County.

The whole project is a National Science Foundation funded effort involving several institutions, including folks at UC Berkeley and the Paleontological Research Institute, to increase public access to Cenozoic marine invertebrate fossils along the Pacific coast of the Americas. And while that means the focus is more on the fossils of creatures like clams and sea snails than vertebrate specimens like our whale ear bone, the project pages are a rich trove of information on everything from the nature of fossils, to best practices for ethical collecting, to the journey of fossils from field sites to museum collections.

This last part is particularly exciting for us, as we work on increasing access to our own collections. And while EPICC and their VFE’s are part of an enormous, national, and multi-institutional effort, they still serve as an incredible model of how many different ways digitized collections can reach people. In the meantime, stop by the museum this month to see this ancient ear bone front and center in the Collections Close Up display.