From glittering blues to shimmering silvers, the ocean punctuates the visual landscape of all who are fortunate to spend time along the Monterey Bay. Yet many of the beauties of the bay are elusive for terrestrial animals such as ourselves. Nonetheless, they can be just as dear to us as our redwood forests. Even now we find ways to connect to them – whether live streaming the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s kelp forest exhibit or exploring tide pools when during low tides.

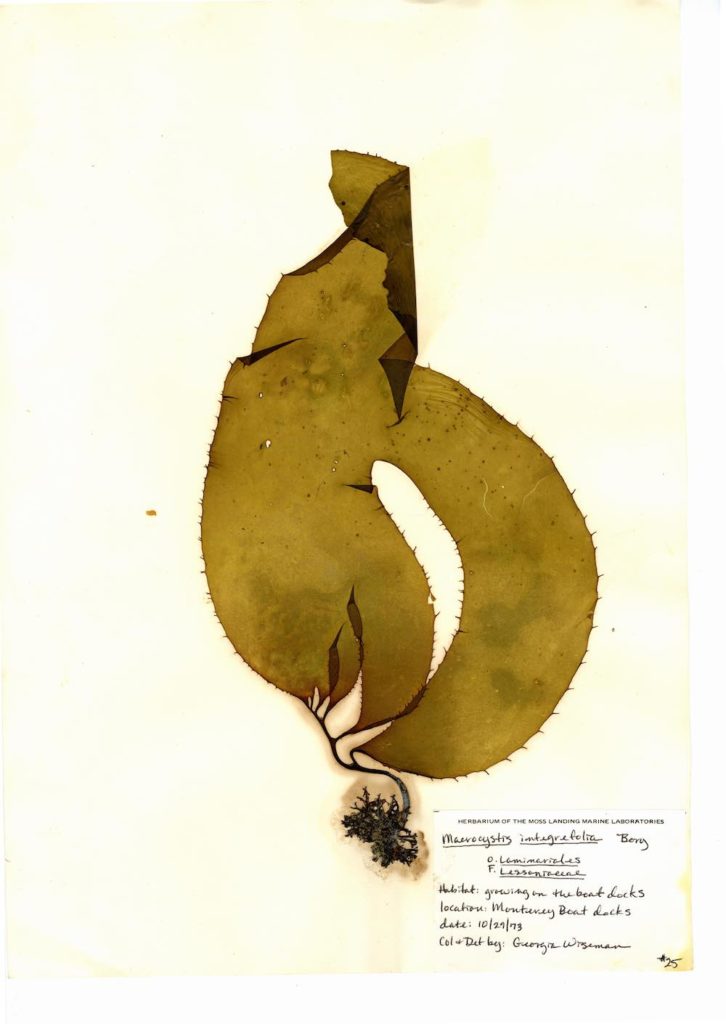

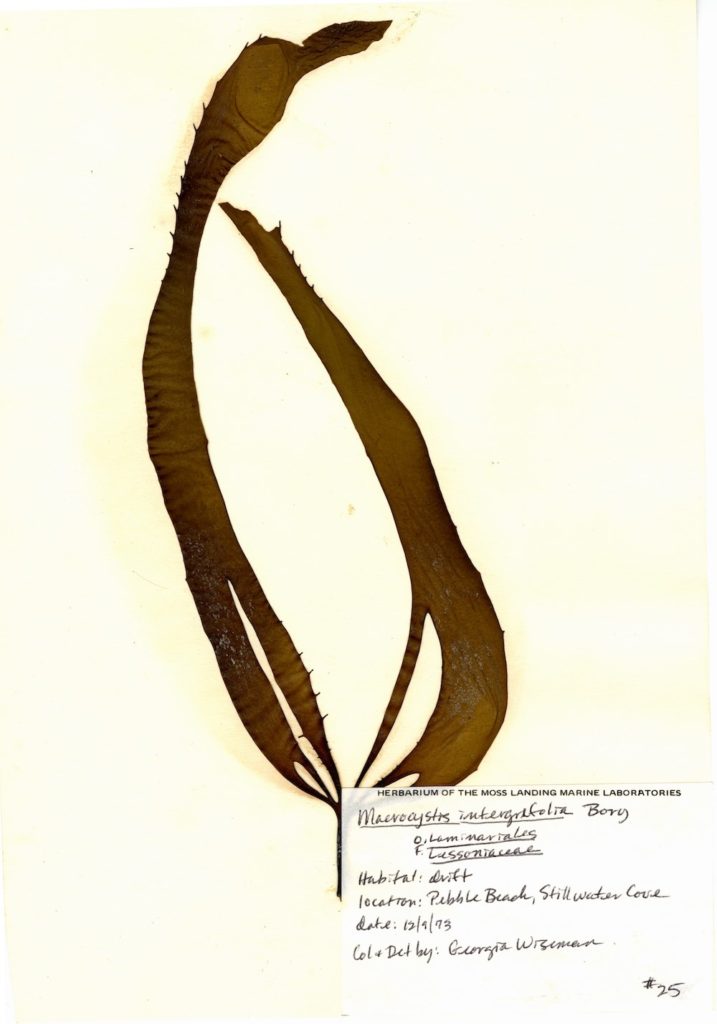

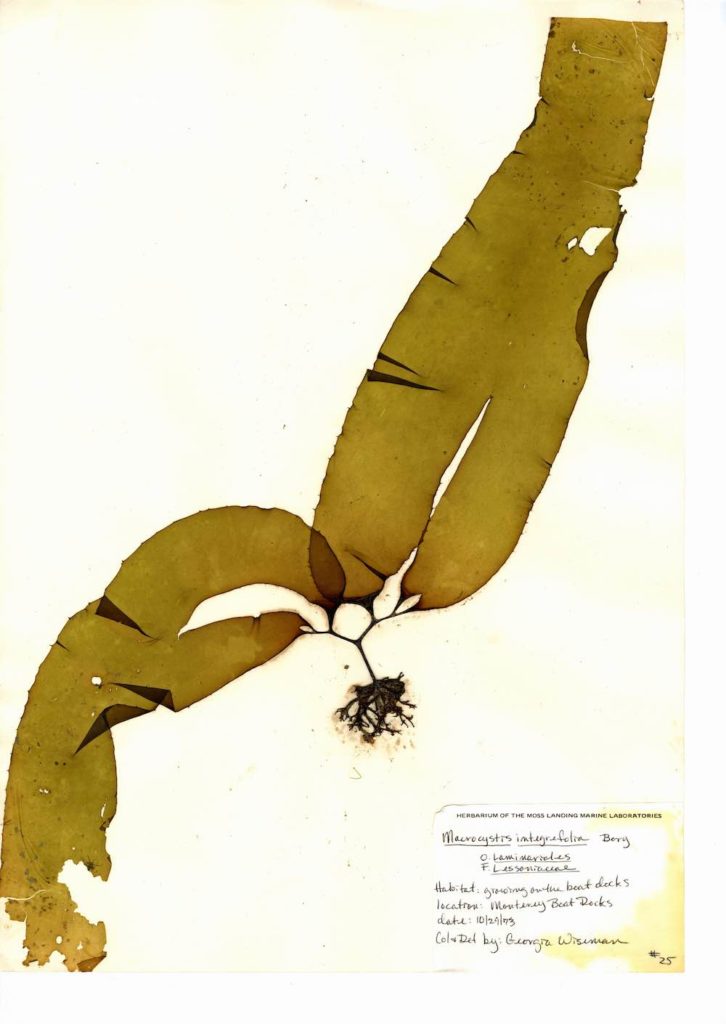

This month, we’re connecting to the museum’s own oceanic treasures, with a dive into our herbarium. Pressed onto paper and accompanied by handwritten collection notes, our collections of marine algae specimens are as beautiful as they are significant in tracking the changes in the bay. For while these specimens have been safely preserved in the Museum’s herbarium for decades, a different kind of preservation campaign is being waged in the ocean outside our doors. And it centers on kelp.

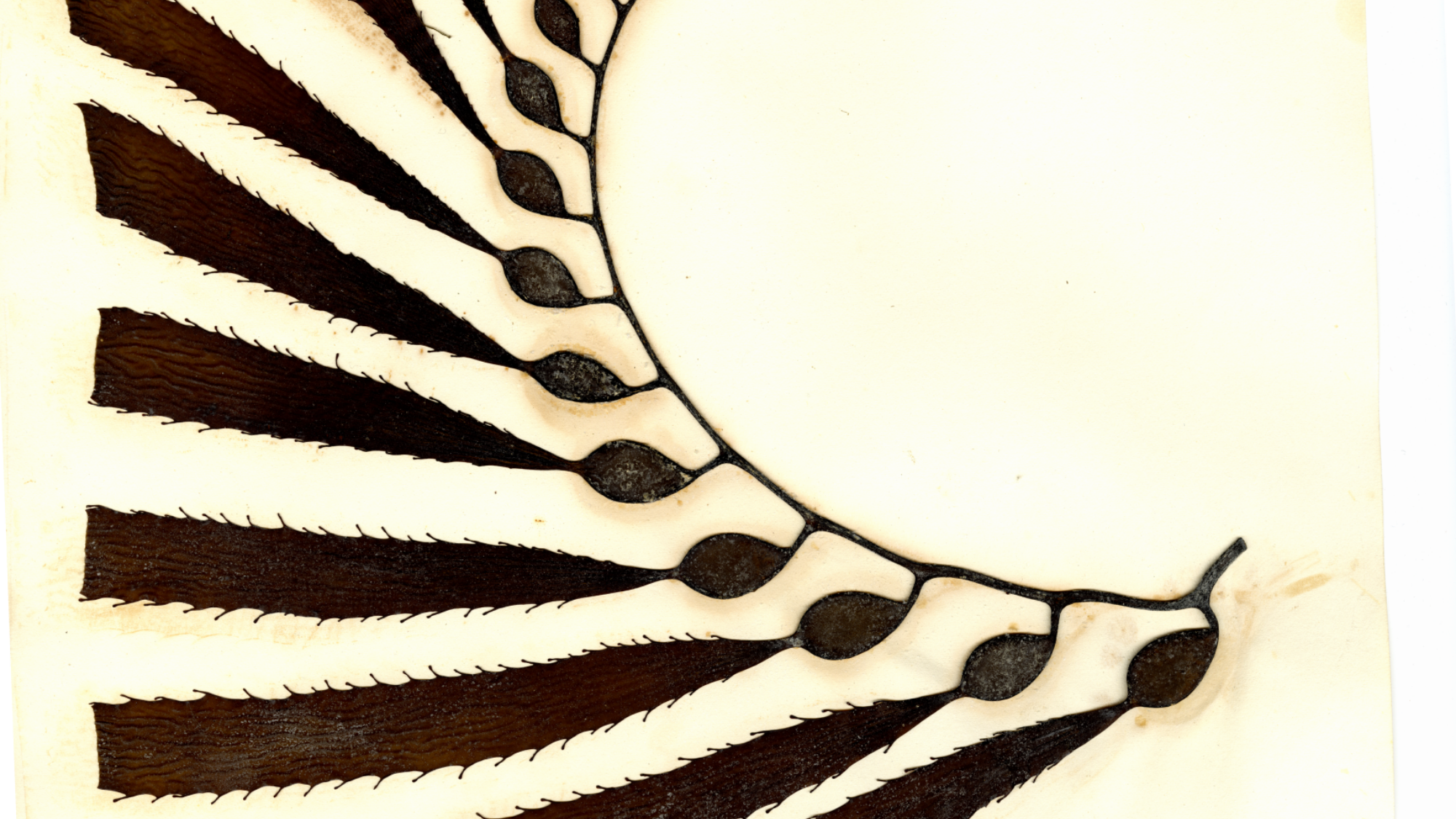

Kelp is the common term for large brown algae in the genus Laminariales. The bigger species in this genus form forest-like canopies in the lower intertidal and upper subtidal ocean floor. One such species is preserved in our collections: Macrocystis integrifolia. In contrast to the roughly 11×17” paper on which pieces of it are mounted, this organism can grow up to 20 feet long. Also called small perennial kelp, it’s scientific name is describes salient features: “macrocystis” is Greek for large bladder, in reference to the gas-filled floats called pneumatocysts that support the leaf-like blades which inspire the species name – “integrifolia” is Latin for “with entire leaves.” At their base, structures called holdfasts attach the algae to rocky surfaces. The holdfasts of M. integrifolia are flatter and branch differently than its more prominent relative, M. pyrifera or giant kelp, although some authorities consider them the same species.

Kelp live in cool, nutrient rich waters where they sustain an immense diversity of life. As both food source and habitat, they support fish like rockfish, invertebrates like abalone, and mammals like sea otters. Humans, of course, interact with kelp forests as well. For thousands of years people have harvested kelp for food, and it is still a common ingredient in many surprising things. More recently it also has been used in manufacturing and medicine. And for several decades, we’ve looked at it for scientific monitoring. Lately, kelp has signaled some alarming changes.

“Marine dustbowl” is the term used by Mike Esgro to describe the scale and impact of the devastation of kelp forests on California’s north coast in particular. And Esgro would know: he is the marine ecosystems program manager and agency tribal liaison for California’s Ocean Protection Council. Keeping one foot in the world of research and another in conversations with tribal members, divers, fisherman and others, Esgro and his colleagues strive to ensure that the decisions made by the state of California to protect its coast and oceans are informed by science.

And we are in need of both good decisions and good news, because California’s kelp forests are being destroyed by what Esgro and others have described as the perfect storm of factors. “Any one of these things would have been bad, but to have them all together was just a disaster”, says Esgro. In 2014, a massive marine heatwave nicknamed “the Blob” warmed up California’s coast and stubbornly persisted through 2016, boosted by a strong El Niño. Among other problems related to these unusual temperatures, kelp has a harder time growing in warm water, which contains fewer nutrients. It is also thought that warm water played a role in the spread sea star wasting syndrome, which led to massive die-offs of sea star populations starting in 2013/2014. The sickness has been particularly hard on sunflower stars, a many-armed sea star that is a key predator for purple urchins. These spiny creatures, who once grazed fast-growing kelp forests in equilibrium, saw a huge population rise as their predators declined due to wasting sickness. Today, these urchins make headlines as the destroyer of these forests upon which they feed.

Of course, ecological stories are always made by multiple actors, and an in-depth discussion can be found in the Great Farallones Marine Sanctuary Bull Kelp Recovery Plan. And while the north coast bull kelp forests have seen a more than 90 percent reduction in their populations, similar problems face the giant kelp dominated ecosystem of southern and central California. The same goes for M. integrifolia, which has a similar ecological role and can often be found alongside its predominant relative.

As a longtime diver and lifelong ocean lover, Esgro is more than scientifically appalled by this situation. He is also heartbroken. Esgro believes an emotional connection is innate to all Californians, whatever form it takes, from surfing to fishing to sea glass collecting. This connection facilitates the work of getting people to care about ocean conservation. For those people who do care, he emphasizes a few crucial actions.

The ways to get involved are as diverse as the ways that people connect to the ocean. Esgro highlights the importance of voting. He does not get to do his job, from promoting solutions to the kelp forest crisis to protecting our coast beyond those forests, if we do not have elected officials who care about the environment. He also emphasizes that it is important to recognize that this is a climate problem, and people need to find ways that they can meaningfully engage with it, both in their personal habits and in how they choose to support the larger systems in our society that contribute to climate change. You can also connect with organizations like ReefCheck, an important collaborator of the Ocean Protection Council, and join the Museum in celebrating World Ocean Day on June 8.

Watch the video presentation about this Collections Close-Up here.