The Central Coast is packed with pinnipeds for all seasons. From regular sightings of harbor seals and seal lions, to special occasions like elephant seal breeding season, which wraps up at the end of this month. An even more special sight would be northern fur seals, who spend more than 300 days a year out at sea. An even rarer sight would be their extinct ancestors, if it weren’t for your neighborhood natural history museum’s fossil display!

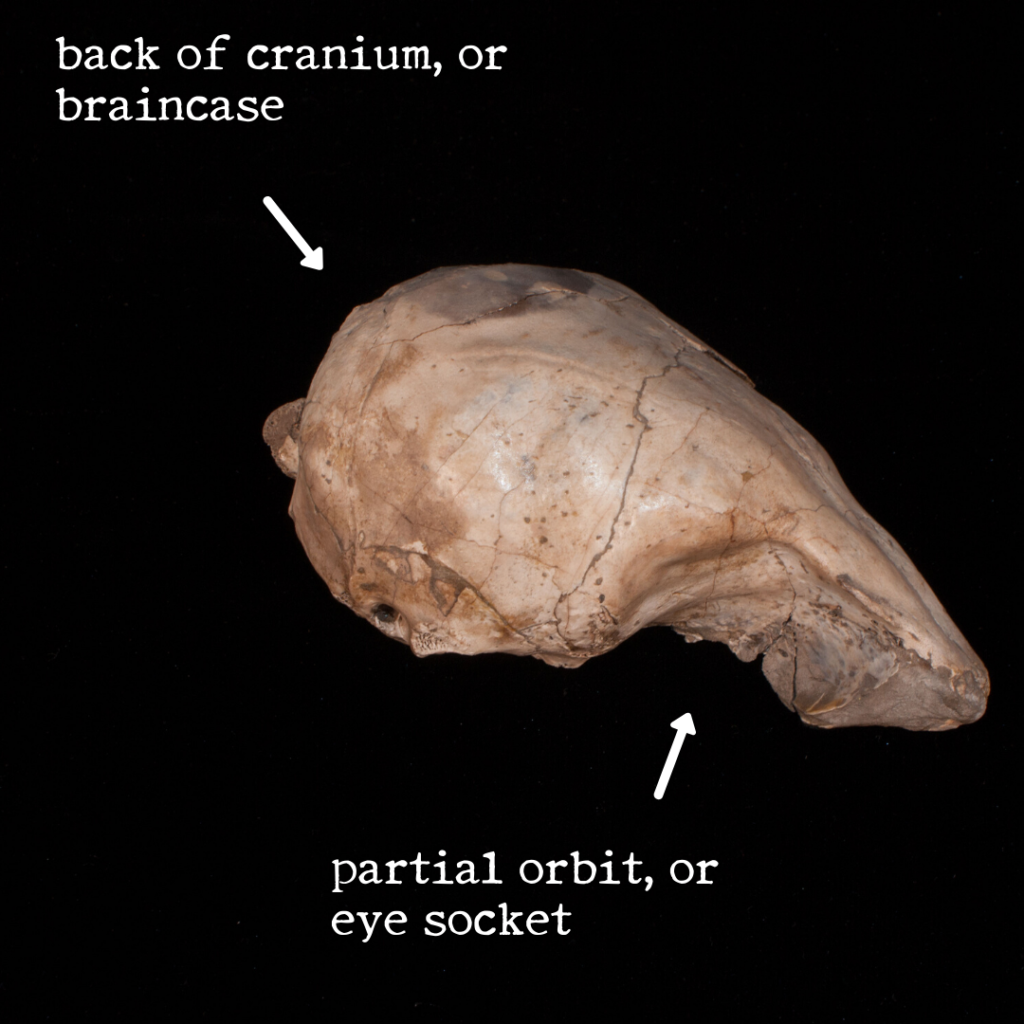

Out from its permanent home in our local paleontology exhibit for a closer look this month, this fragmentary fossil is a partial cranium and frontal skull region of the ancient pinniped Thalassaleon macnallyae. Compare this specimen to modern pinnipeds, including their descendant the northern fur seal. Thalassaleon means sea lion in Greek, and is the name of an extinct genus of the family. Thalassaleon means sea lion in Greek, and is the name of an extinct genus of the family Otariidae. Otariidae, including fur seals and sea lions, are a group of carnivorous semi-aquatic marine mammals with flippers and visible external ears. Together with Phocidae, the earless or true seals like harbor seals, and Odobenidae, whose only living member is the walrus, and the extinct Desmatophocidae family, these families make up the clade of pinnipeds.

This fossilized cranium, which belonged to an immature individual, was collected but not identified from near Soquel Point by teenager Gerald Macy in the late 1930s or early ‘40s. Many fossil hunters have cut their teeth collecting along the Opal Cliffs, and Macy was no exception. In 1939 the local paper described the then 17-year old as “the local authority on paleontology, a position attained by more than five years painstaking search of the rich stratas [of the cliffs]”.

While the cliffs of Capitola have exposed countless fossils for science, they are special for this species: Thalassaleon macnallyae has only been found in exposures of the Purisima formation in Central and Northern California. The first of its kind to be formally described was uncovered in Point Reyes by paleontologist Kathleen MacNally Martin in 1965. As a whole, this species has a geochronologic range of 6.9-5.33 Ma.

As the ancestor of the modern northern fur seal, this specimen represents millions years of life in Santa Cruz. Today its descendants spend most of their time on the open ocean where they feed on a variety of fish and squid. They come ashore to reproduce and molt on rocky or sandy beaches of islands in the eastern North Pacific and Bering Sea, including California’s San Miguel Island and South Farallon Island. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, they were hunted for their luxurious pelts: their insulating fur boasts 46,500 fibers per square centimeter. Although they are now protected, they face threats from debris entanglement, fisher interactions, and climate change throughout their range.

Our ancient fur seal specimen’s story doesn’t stop with its own descendants – it also has a role in putting together the puzzle pieces of pinniped evolution. Its measurements, along with those of a variety of other pinniped fossils, were used by paleontologists Robert Boessenecker and Morgan Churchill in 2015 to identify an older species of fur seal – Eotaria crypta, the oldest discovered otariid specimen.

Boessenecker was looking through pinniped fossils at the Cooper Center in Orange County in 2012 when he spotted a small fur seal jaw whose identification seemed at odds with the age of the rock formation in which it was found. He suspected that the specimen might represent a missing link between otariids and the ancient ancestor of pinnipeds from which they diverged.

To confirm, the paleontologists analyzed more than 115 morphological features from specimens representing more than 23 taxonomic groups, including the star of this month’s Close Up. By preserving fossils like the remains of Thalassaleon macnallyae as well as others, our collections can further our understanding of the history of life on earth.

We couldn’t do that without the paleontologists who put in the work to study our collections, and we were thrilled to talk to California native Robert Boessenecker about what that process looks like.

He says that the decision to study a fossil begins with how interesting it is – whether it helps tell a story, fill a hole in current knowledge or has unusual features or strange preservation. From there it takes a combination of fieldwork, fossil preparation, museum visits, and data collection to understand a fossil’s significance.

Boessenecker, who teaches at the College of Charleston and blogs about his research, is no stranger to SCMNH. Bobby, as he is often referred to in our records, has been hunting for fossils in Santa Cruz since he himself was a teenager, and has gifted some of his finds to our museum. This kind of collection, he says, is perhaps unique to the field of paleontology – how easy it is for community scientists (e.g. amateur fossil collectors) to make serious contributions to science.

Stop by this month to check out one such contribution – our fossil fur seal in focus.