“It’s the end of the world!”

Thus interrupts the drunk man from the corner of the bar, as the leading lady of Hitchock’s The Birds tries to get some answers. Outside in the sleepy town of Bodega, California, birds are everywhere. They’re massing at playgrounds, dive-bombing pedestrians — malicious attacks, intentional and murderous. It just so happens that one of the bar’s customers is an ornithologist – a baffled bird scientist who insists that birds don’t have the brain power to mount a deliberate attack – and yet, we know how serious the situation gets.

This month’s Collections Close-Up highlights the protagonists of Monterey Bay’s real life The Birds episode, as we explore how scientists, using historical museum collections, can help us understand the natural world even when things seem bizarre or scary.

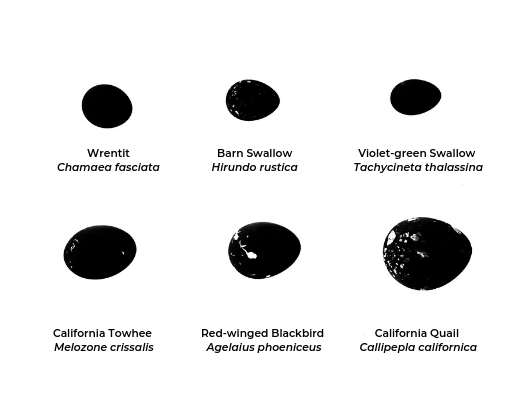

Sooty shearwaters (Ardenna grisea) like this one are seafaring birds that spend most of their lives on the ocean. Named for their rich gray-brown plumage, the birds have gray beaks and feet with a brush of silver-white under the wings. Sooty shearwaters complete a remarkable annual migration. Each year they cross a whopping forty thousand miles round trip from nesting sites in the Southern Hemisphere to the nutrient rich waters of the north Pacific, in one of the largest mass migrations known. Here off the coast of California, you can see them from mid summer to mid fall. The shearwaters can be observed in the summer, diving down as far as 200 feet, “swimming” with their wings in pursuit of anchovies and squid.

Sadly, sometimes they get more than they bargain for.

One such occasion, a hallmark of local lore, was rumored to have inspired Hithcock’s horror film. Around 3:30 in the morning on August 18, 1961, thousands of sick sooty shearwaters began slamming into the coast of the Monterey Bay. As they fell against homes, cars, and streets, primarily in Capitola, they disgorged half eaten anchovies. Some frightened folks were even bitten by the crazed birds. Municipal services struggled to clean them up.

Two years later, Alfred Hitchcock released The Birds. We know that the Capitola incident caught his eye — he even called the editors of the Sentinel to ask about the news. However, at the time of the so called “Seabird Invasion” Hitchcock was already at work on a project inspired by British author Daphne DuMaurier’s 1952 novella of the same name. As Capitola Museum’s Frank Perry points out in a Santa Cruz Waves article on the incident, that the sad fate of the sooty shearwaters mirrored the film was simply a coincidence. And where both stories portray their avian antagonists with a malicious intent, the actual culprit is more concrete: domoic acid.

Domoic acid is a neurotoxin produced by diatoms in the Pseudo-nitzschia genus. When these single-celled photosynthetic organisms occur in high numbers, the toxin can build up in the fish and shellfish that eat them. While it doesn’t appear to harm them, as it accumulates up the food chain to birds and mammals, it can cause lethargy, dizziness, disorientation, seizures and death. In humans, those symptoms can include irreversible short term memory loss.

Today, when seabirds are discovered with symptoms consistent with domoic acid poisoning, swift treatment can save their lives. This was not an option in the 1960s, in part because the mechanism of the poisoning was not yet known. While scientific work on domoic acid began taking off in the 1950s, it wasn’t until a major die off of pelicans and cormorants in 1991 that researchers began monitoring the presence and effects of domoic acid in the Monterey Bay. Within a few years, scientists began suggesting that domoic acid poisoning was also at play in the 1961 event.

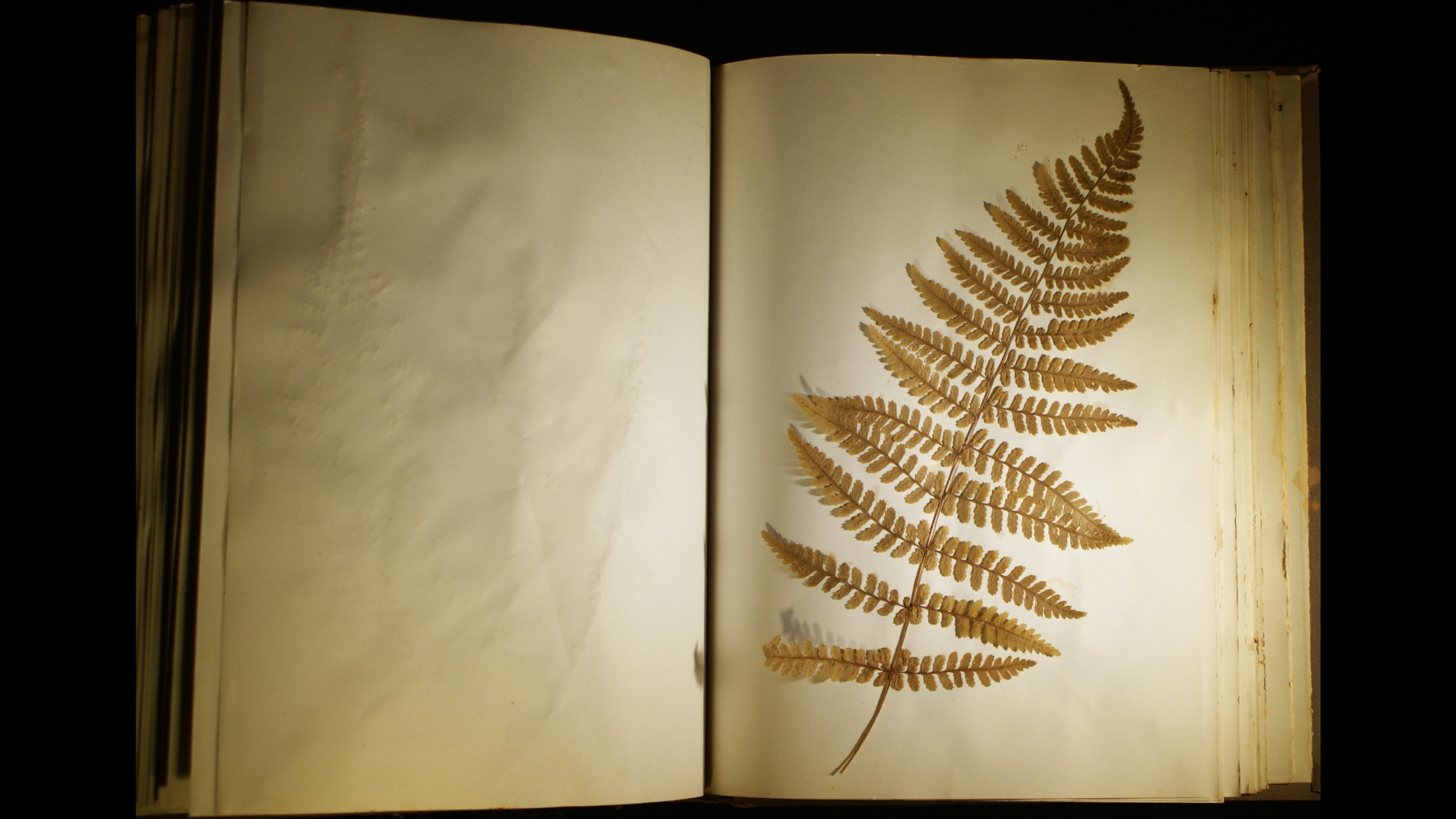

In 2012, a team of researchers at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, intent on solving this scientific whodunit, examined the guts of zooplankton samples harvested in 1961, a few months before the berserk birds hit Capitola and the surrounding area. They confirmed sufficiently high levels of domoic acid-producing species of Pseudo-nitzschia diatoms had been consumed by zooplankton, who would in turn be eaten by the anchovies that poisoned the birds that ate them. As one of the researchers excitedly pointed out, historic specimens can provide answers that nothing else can, and in ways that were never imagined by the scientists who collected them.

The story certainly doesn’t end there. High levels of domoic acid in the food chain is a form of Harmful Algae Bloom. Also called HABs, these events are on the rise. HABs occur when there is a spike in the growth of algae with negative consequence for their surroundings, such as the accumulation of toxins or the depletion of oxygen. They occur when an excess of nutrients builds up in waterways, and are often associated with higher temperatures and stagnant water. Scientists are working to understand these occurrences and their complex consequences through monitoring projects across the California Central Coast and beyond.

If toxic algae blooms are a little too dystopian for you, check out this year’s Museum of the Macabre for a more classic scare. We’ll be highlighting the natural and cultural history of our sometimes frightening feathered friends, from Hitchcock horror to ancient omens and beyond. Set the spooky mood by locking eyes with our very own Sooty Shearwater on special display for October’s Collections Close-Up.

References available upon request.