Since long before Laura Hecox hauled her petticoats across the rocky and rich worlds of West Cliff’s tide pools, the natural wonders of Monterey Bay have captivated all who encounter them. Pounded by the mighty surf and subject to the extremities of the changing tides, the plants and animals of the intertidal zone are especially intriguing. Efforts to get closer to these and other creatures held within the depths of the ocean gave rise to the modern practice of holding marine life in aquariums. This month we explore our interactive side by examining a special form of this phenomenon: the museum’s touch pool.

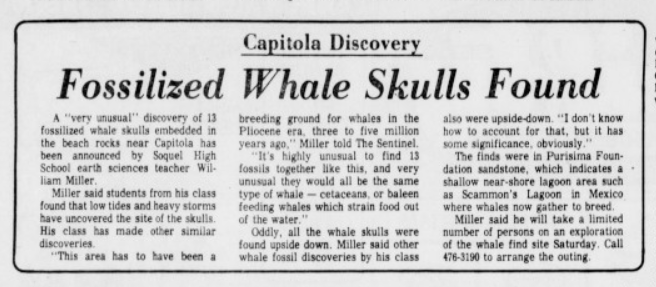

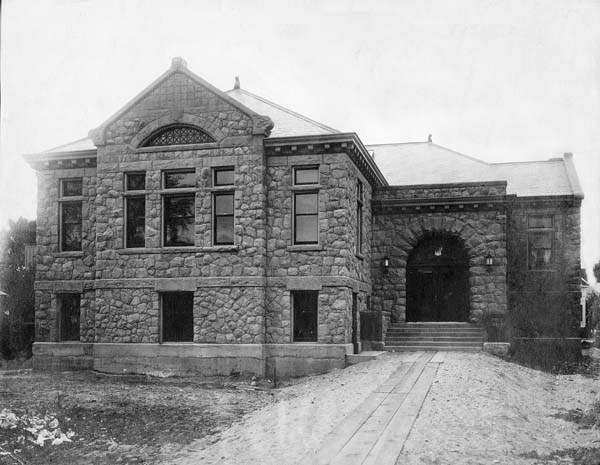

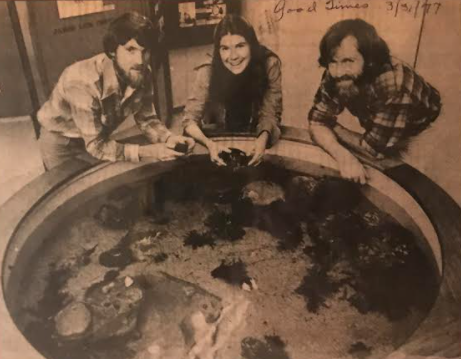

To the outpouring of public delight, what was then the Santa Cruz City Museum poured gallons upon gallons of seawater into our first touch pool in 1977. Curator Charles Prentiss designed this pool, which was built with the assistance of Museum friends and local companies. It consisted of a circular fiberglass tub, collared by redwood boards. An educational structure from the start, the edges of the pool were inscribed with labels describing the life teaming within. A particular fan favorite, featured often in local news articles, was any kind of sea star.

Early on, the Museum hosted classes on marine life in tidepools and the broader ocean, both at this interior pool and along the local coast. Touchpools have long offered direct and accessible engagement with seldom-seen creatures from another world. From the outset, gentle engagements with the animals have been a must, as the modern use of aquaria and touchpools emphasize their function as tools for the empathy and conservation of wildlife – an especially tricky task for animals that aren’t typically seen as charismatic as big cats and beautiful birds, like prickly urchins and slimy sea slugs.

The Museum’s original touchpool was brought into being during a boom in local marine science and conservation construction. The Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation formed in 1978, and successfully opened a world class aquarium showcasing the bay’s unique marine environment in 1984. UCSC’s Long Marine Lab was first opened in 1978, a research lab with early public facing components that ultimately developed into today’s incredible Seymour Marine Discovery Center.

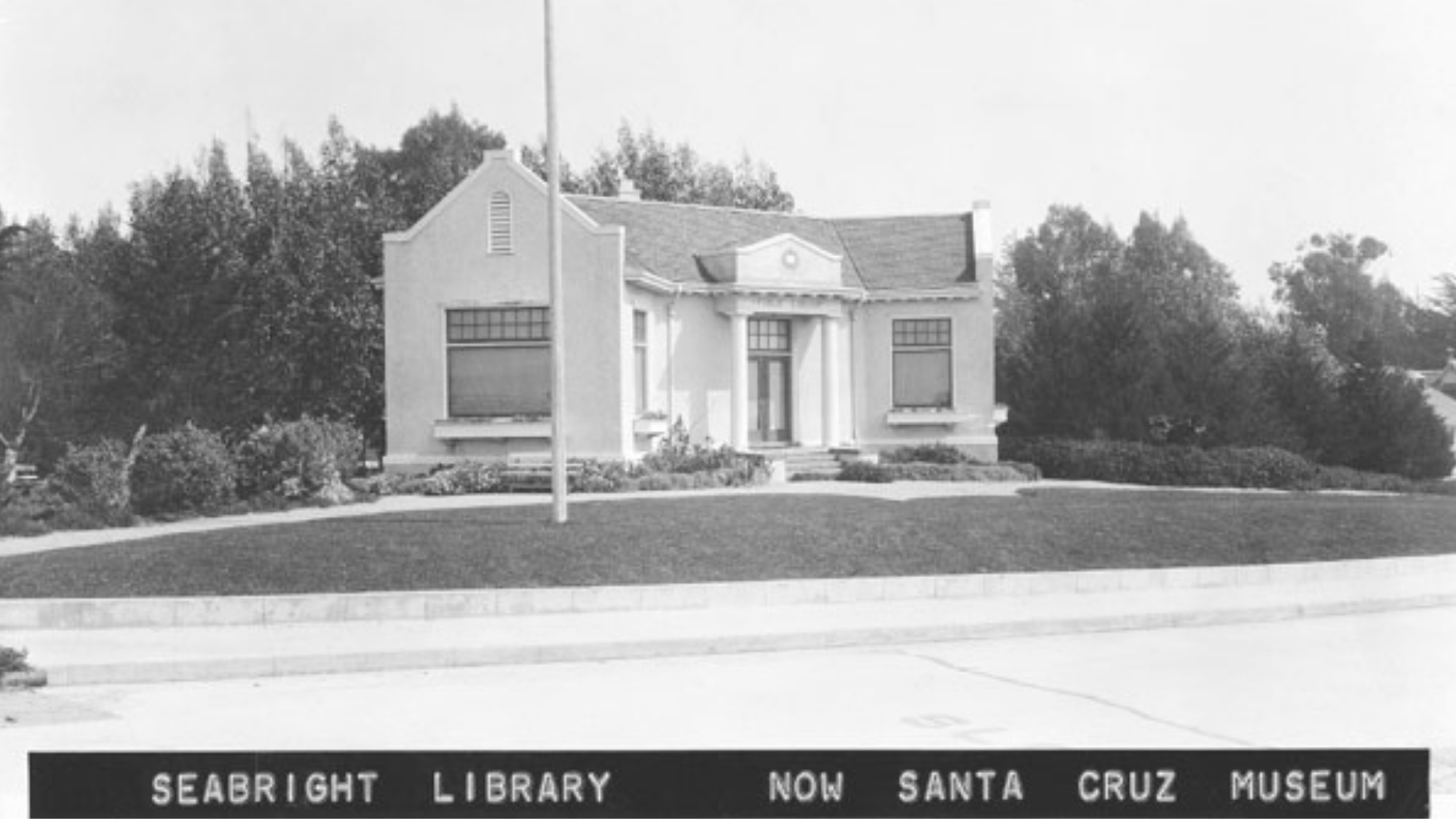

The initial boom in the popularity of aquaria was driven by a sense of wonder, though with a greater focus on rampant collection rather than empathy and conservation. The first burst of aquarium popularity was inspired in the 1850s by Englishman Phillip Henry Gosses’s books on aquarium construction, specimen collection, and observation. Packed with stunning illustrations and spell binding descriptions, the coastal collecting mania Gosse’s work inspired overtook middle class Victorian fern fever and bolstered support for the creation of large public aquariums. Long before the institutions above created their own aquaria, a fascination for the “natural aquariums” of Seabright led local residents to bring bathtubs to the beach and fill them with tide pool creatures in the late 1800s. In her Reminiscences of Seabright, Elizabeth Forbes notes that despite the community’s best caretaking efforts, the creatures were unhappy, and they were returned to the sea before too long.

Today’s Seabright touch pool depends upon special permits and CA Fish and Wildlife Department regulations for the collection, care, and use of specific marine plants and animals. Rebuilt in 2016, the current pool provides enhanced physical accessibility through the use of low-slung walls and clear sides, while portraying a more realistic sense of the tidepool with its rocky border aesthetic. Housed within the SC Naturalist Exhibit, the pool pays homage to the life of our foundational collector Laura Hecox, whose story of being an untrained female nature observer at the turn of the 20th century illustrates how anyone, regardless of formal credentials, can be a naturalist.

In 2020, we’re still appreciating algae and asking naturalists how best to start tidepooling – but we’re doing so at safe distances or masked. In the same way, Covid19 has implications for the care of our living collections. In general, the pandemic has been difficult for zoos and aquariums whose obligations to care for their animals and plants do not get any cheaper even as they lose funding from admission prices. The lack of admissions also means that animals are becoming shy of human guests – losing a level of comfort that is important for the well-being of the animals and the success of the exhibit.

While our living collections are small in scale compared to other institutions, they still take special consideration – like making sure we have lights on timers to extend the “daylight” our touch pool residents would have experienced during normal open hours. A return to open hours presents its own new problems – how might the delicate balance of water chemistry be changed by an influx of extra hand sanitizer?

For more about the nuts and bolts of what it takes to keep our touch pool running, in both ordinary and extraordinary times, as well as the educational and ethical dimensions of working with these plants and animals in our upcoming event, Tidepools and Touch: Care for Living Collections.