Have you ever found a fossil?

It’s hard to walk along many of our local beaches without encountering the fossilized forms of whales or sea lions and the ornate whorls of ancient shells. These old organisms are made visible, in part, by the effects of weathering and erosion. While these forces are active all the time, a good storm can come along and shake open whole new windows into the past.

Some fossils you can even find in our front yard, literally.

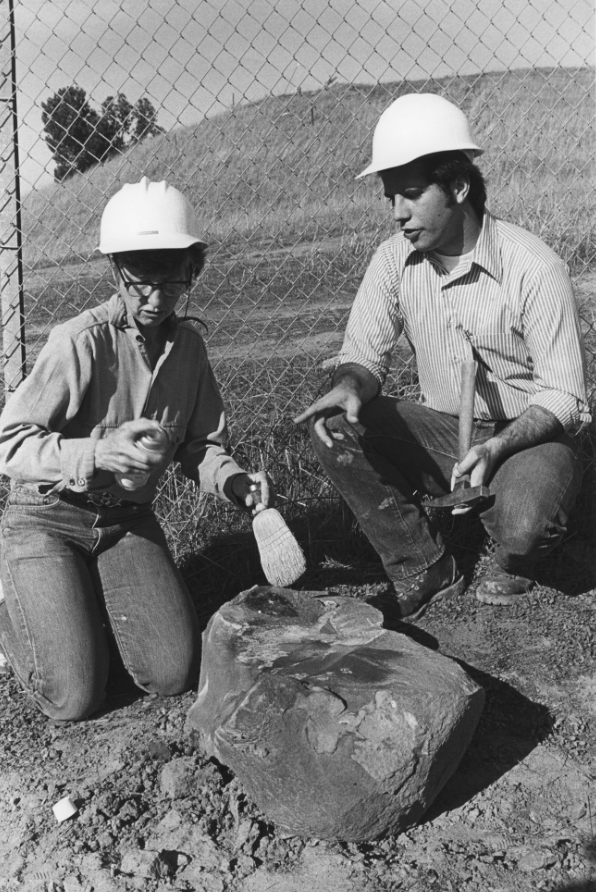

The large specimens situated on the whale statue (southern) side of the museum’s garden are, thematically, the remains of ancient whales from Purisima formation outcrops in Capitola. Between 4.4 and 5.5 million years old, these specimens include an ancient ribcage (see above image), whose head would be oriented towards the beach if it were still attached. And although skulls are always interesting, we are lucky to have such a complete ribcage. The inherent movement of the ocean, the activities of scavengers, as well as the potential for marine mammals to “bloat and float ” upon their demise, often result in the slow and scattered disarticulation of the organism. Speaking of skulls, the other two specimens on display in this part of the yard do contain whale skulls (below images left and center). If you look closely, you can see the visible ear bone in one, while the other is partially obscured by the phalanges of an ancient flipper.

Fossil whale skull

Fossil whale skull and phalanges

Fossil whale vertebrae and upper limbs

Other fossils tell the story of a different type of discovery – that of human intervention in the landscape. The specimens peeking through the Fuschia and hummingbird sage beneath our gift shop windows (above right image) take that story further, to the surprisingly intertwined history of paleontology and physics.

Fourteen million years ago, the coast of California was quite differently shaped. In parts of what is now terrestrial San Mateo County, a shallow, high-energy marine environment brimmed with life. Crustaceans burrowed in sand below swimming sharks and wandering whales. The organisms present, based on fossil evidence, indicate a nearshore to open shelf marine environment.

Fifty-seven years ago, a bulldozer cut a little too widely into the petrified remains of this ecosystem, a green-gray to light gray rock formation now called the Ladera Sandstone. In doing so, construction workers on what is now SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory discovered the remarkably well-preserved and almost complete skeleton of an ancient hippo-like creature now called Neoparadoxia repenningi. Prior to this discovery, this roughly cow-sized herbivore had only been known through specimens of preserved teeth. The value of the find became clearer and clearer as, with the efforts of experts from Stanford and USGS and beyond, all but the head of the organism emerged from the surrounding stone. The UC Museum of Paleontology at Berkeley (UCMP) agreed to curate this significant specimen in exchange for providing casts.

Adele Panofksy with Neoparadoxia model

Courtesy SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

1977 Discovery Site

Courtesy SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

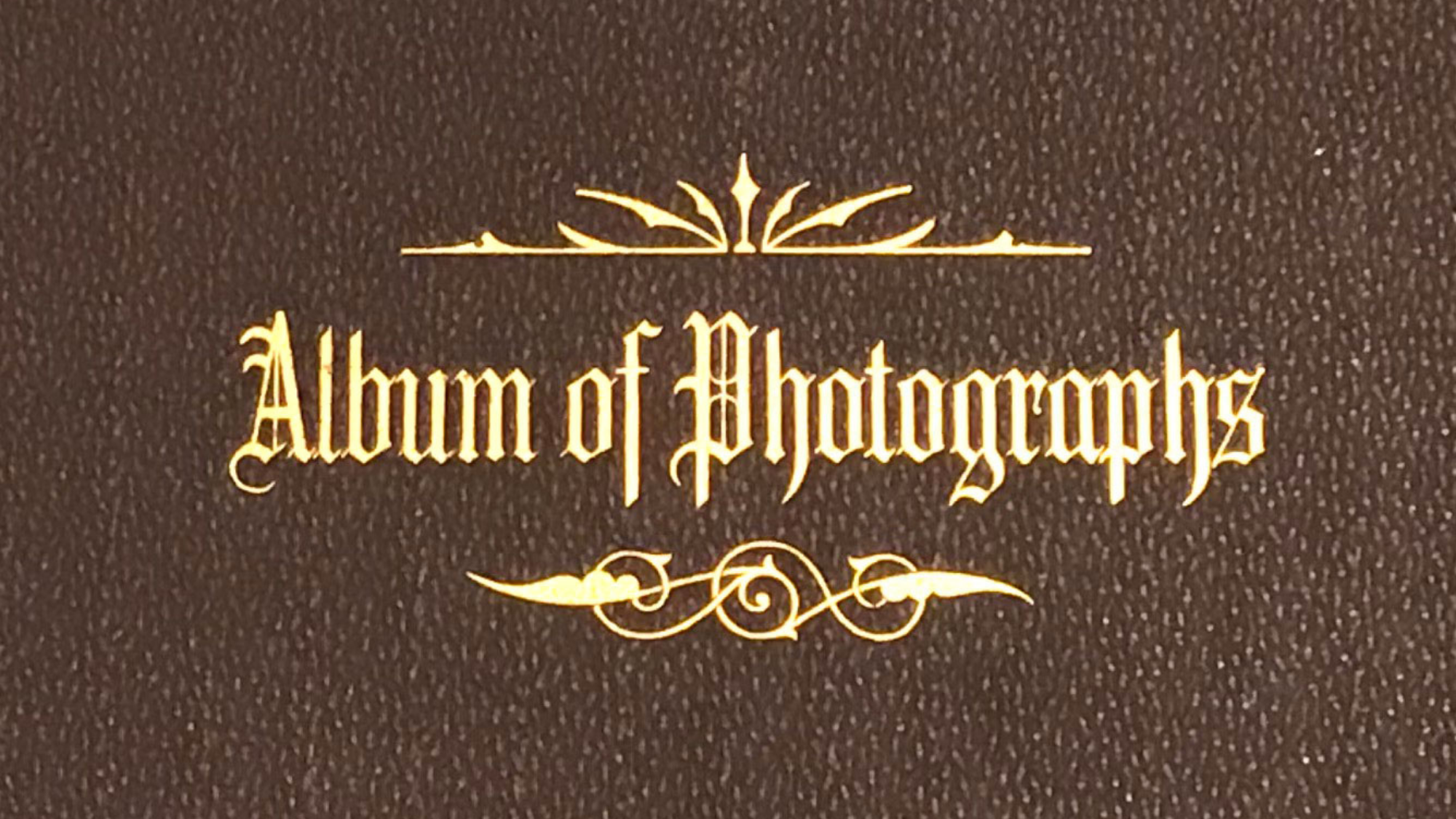

Adele and Bruce in 1977

Courtesy SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Casts which became the life’s work of the wife of SLAC’S then-director, Adele Panfosky. Alerted to the discovery when taking a phone message for her husband Wolfgang, Adele immediately drove to the site. What started as an opportunity for an interested volunteer without formal training to assist with excavation turned into a decades long quest by a budding paleontologist to create a complete and accurate Neoparadoxia model. Over the years Adele collaborated with scientists from around the world, ranging as far as Japan’s National Museum of Science and as close as local museum member Frank Perry, who cast some of the teeth for the display.

Fortunately for us, the Neoparadoxia wasn’t the only specimen uncovered at SLAC. In the late 1970s, the campus was expanded to include the Positron Electron Project or PEP ring, digging further into the Ladera Sandstone. All told, the remains of ancient whales, porpoises, sea lions and at least six different kinds of sharks were unearthed. Scientifically significant specimens were again sent to UCMP. When it came time to find a home for specimens that were more useful for educational display than science, Adele arranged for several to be gifted to our Museum here in Santa Cruz. You can still find these on display in our garden today, now with the additional context of the specimen descriptions provided here.

- Concretion with several bone exposures; long narrow straight exposure may be a partial marine mammal mandible

- Two specimens containing sections of whale mandible

- Partial whale skull in ventral view

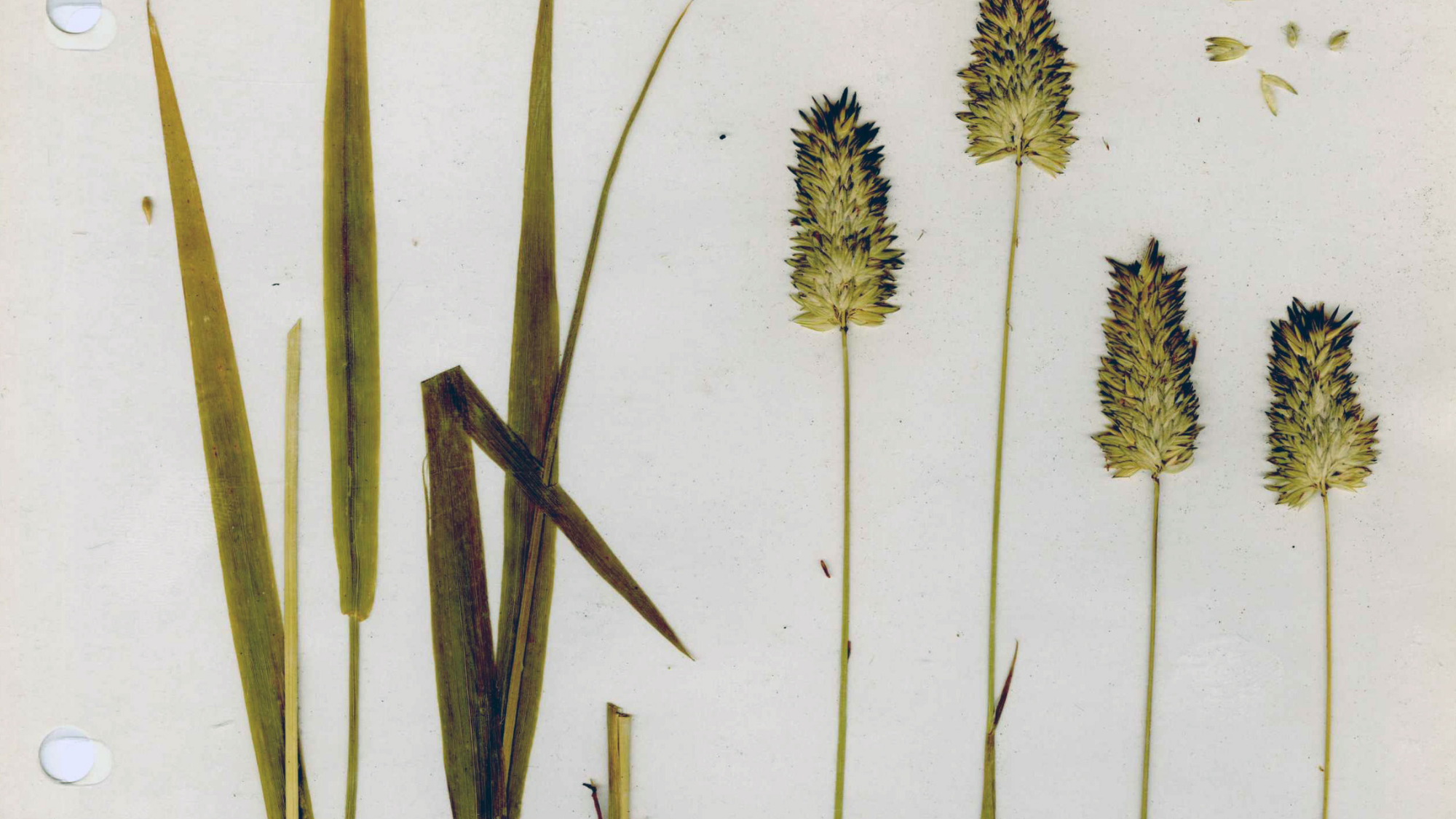

- Cross section of whale cervical vertebra and fragments of other vertebra and upper limb bones. Fragment of humerus scapular joint preserved separately

Meanwhile at today’s SLAC, now with a new name and an expanded research profile, scientists are circling back to fossils once more, using advanced x-ray imaging techniques to determine the original colors of ancient creatures.

If you find these discoveries exciting, nurture your own passion for paleontology: check out our fossil guide to explore our local landscapes with fresh eyes, and join us for our October Collections Close-Up event, to be held on October 13th, National Fossil Day, all about Fossil Walruses and Other Ancient Life in the Monterey Bay with Dr. Robert Boessenecker.