Open the delicate pages of this month’s close-up item and you’ll find ferns from long ago. Though carefully pressed and arranged, this pressed plant album doesn’t tell us which species are on display or where they were found. It does, however, offer some perspective into female participation in 19th century science— a relevant point during Women’s History Month — and how people from the Victorian era explored nature through these ancient plants.

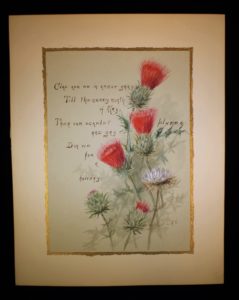

A purpose-built seaweed collecting album, the engraved cover is entitled “Sea Moss,” though no moss or seaweed rest inside. Some pages feature single specimens. On others, a mixed array of leaves and branches almost leaps out at the viewer. In a time where traditional scrapbooking was a popular pastime, books like this were sold to support the collecting and pressing of seaweeds and other plants.

It is one of several albums once part of the James Frazier Lewis estate. Lewis was a son of Donner Party survivor Martha “Patty” Reed Lewis, who had settled in the Santa Cruz area. This collection was given to the Museum in 1945, with a note suggesting that the albums were made by Mr. Lewis’s daughters. We know very little of these possible authors, though, and Lewis’s obituary lists him as survived by a sister and a niece.

This recorded silence on the subject of women is unsurprising, although it is an absence that is being excavated more and more. And it is indeed likely that these albums were made by women. The Victorian era witnessed a widespread seaweed-collecting craze. Yet it was women, already the more prolific scrapbookers, who were the most prolific creators of these pressed albums.

Artistic arrangements of plants, whether fresh or pressed, from land or sea, were considered an appropriate and healthy hobby for young women at a time when their participation in the natural sciences was generally rebuffed. Whereas the men who made pressed plant albums could engage more formally in the emerging profession of botany, female collectors were encouraged to make sentimental and decorative displays.

That does not mean they were not active in furthering the field, of course. Recent scholarship acknowledges the importance of the female contribution to botanical fields through non-professional botanical societies. Similar realities unfolded in other disciplines, such as the case of Laura Hecox. An avid naturalist without formal scientific training, Laura’s correspondence with scientists even resulted in two species being named after her: a fossil snail and a type of banana slug.

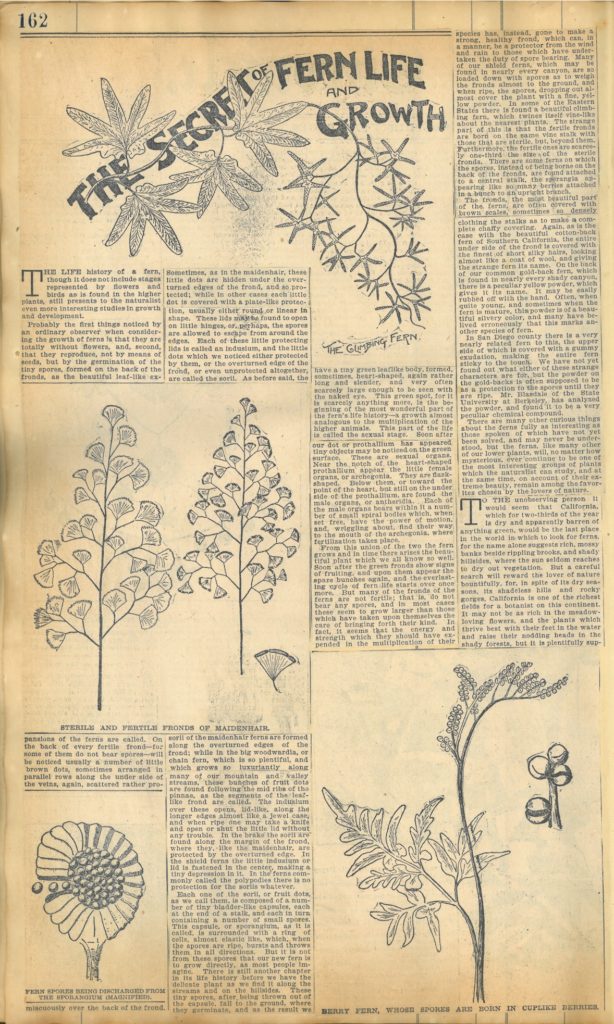

And how do we find ourselves with a sea moss album featuring ferns? Because pteridomania, or fern fever, also reverberated through Victorian culture. Fern-hunting parties were the rage, ferneries or fern gardens decked houses both large and small, fern motifs exploded across arts and crafts, and pressed ferns were gathered into albums.

This craze was made possible in large part by the invention of the Wardian case by Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward in 1829. An early version of the terrarium, these sealed glass cases let British folks bring a variety of exotic plants into their homes, including the ferns that naturally grew happier in the wetter and wilder parts of Britain.

Some also suggest the late 18th century discovery of fern reproduction via spores promoted specific interest by allowing collectors to propagate them at home, in addition to collecting. In one of her scrapbooks, Laura Hecox saved a beautiful article on ferns some time in the late 1890s.

And lest you think pteridomania has disappeared — the American Fern Society, founded in 1893, is still kicking. They promote the cultivation and study of ferns, and have a solid introduction to ferns on their website. Our very own Museum even hosted a Fern Festival in March, 1980. A collaboration between the Natural Science Guild of the Santa Cruz Museum Association and the local Native Plants Society chapter, this three-day event “celebrate[d] the variety and beauty to be found in ferns.”

Stop by the Museum this month to take a closer look at some fabulous pressed ferns. Botanically speaking, March at the Museum also includes a native plants garden design workshop on the 7th, as well as our twice monthly Saturdays in the Soil volunteer gardening program.