Small mammals conjure a wide range of emotions, from disgust at the sight of a rat in the kitchen to affection for a chipmunk’s fuzzy face. The diversity of these animals is just as varied as the feelings they inspire — in Santa Cruz County alone, surprisingly many different species of mice, rats, moles, and gophers tunnel under our feet and climb branches over our heads. We may rarely see them out in nature, but they encompass a diversity that’s sometimes overlooked.

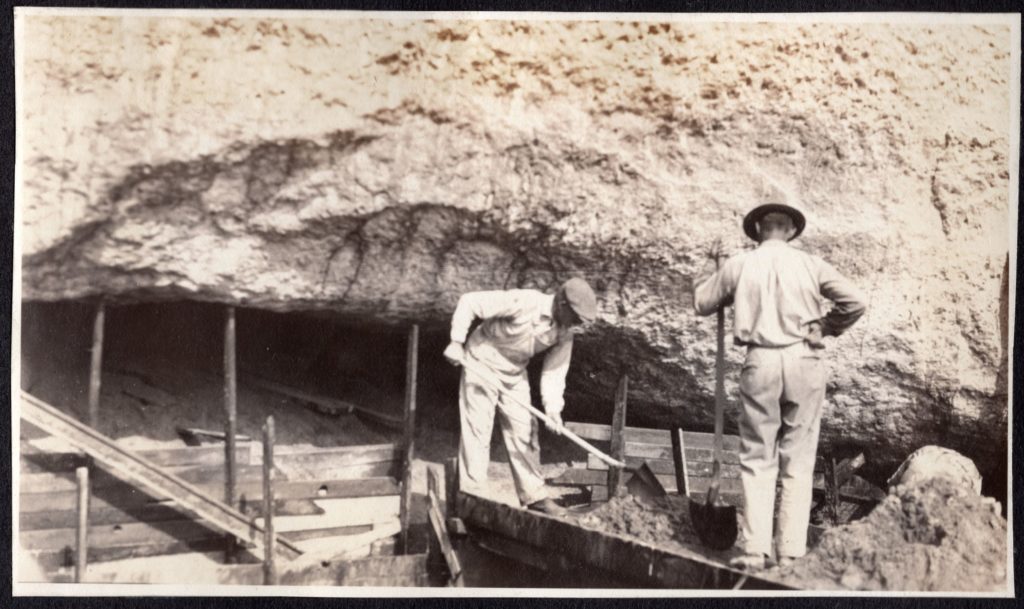

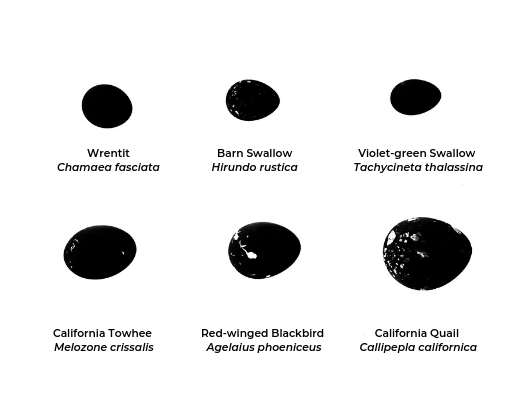

This month, we’ll introduce you to a few members of these small but impactful creatures, along with some local research efforts to better understand them. Our collections hold a number of specimens ranging from the petite harvest mouse to shrew moles. While some of these are taxidermy mounts designed for diorama display, many are study skins.

Study skins are effectively stuffed pelts that allow for compact and safe storage for future research. Researchers can pull chemical information from the fur to glean details about an animal’s diet or compare coloring across specimens to find evolutionary forces at work.

First, let’s explore the California mouse, or Peromyscus californicus. Because they’re nocturnal, small and fast, you might at first think this species is the same as the house mouse, or Mus musculus. In fact, the California mouse is larger, distinctly bi-colored with a white belly and tends to live in the burrows of larger animals across California chaparral and woodland, rather than in close association with humans.

Discovering the subtle differences that enable similar looking species to thrive in the same environment is part of what captivates rodent researcher Chris Law, who collaborated with us for this post. Law will start a postdoc at the American Museum of Natural History this fall and recently earned his PhD in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology from UCSC. While his research primarily focuses on sea otters, Law worked as a graduate mentor with UCSC’s Small Mammal Undergraduate Research in the Forest project, or SMURF, whose aim it is to monitor small mammal populations in Santa Cruz County while providing opportunities for undergraduate students to do hands-on field work.

As part of his research, Law investigated the dietary habits of mice by studying their bite force. Coaxing mice to bite onto measuring devices can be tricky, it turns out, so Law also studied skull morphology to round out his research. The differences he saw helped explain the preference these species seem to have, Peromyscus californicus for arthropods like insects and spiders and Peromyscus truei for acorns, which enables their success living side-by-side in the same ecosystem.

One reason why it’s important to learn more about small mammals, despite their seemingly inconsequential size, is because shifts in their population can warn us of problems elsewhere. Because they are lower on the food chain than many other animals in a given ecosystem, changes in their population reverberate through the population levels of the animals that eat them and the animals that eat those animals.

Against this backdrop, finding a species can be just as important as not finding them. For example, in a 2017 project, undergraduate SMURF researcher Deanna Rhoades tested several sites in Felton where kangaroo rats once roamed. They found none, which, along with other records of a population contraction, means the rats are likely extinct in parts of their previous range.

Dusky-footed woodrats (Neotoma fuscipes), on the other hand, are common throughout Santa Cruz. These rats, distinguishable from non-native black rats in part by their furry tails, are sophisticated architects and builders. Their homes, which can have a variety of different chambers and persist for 20 to 30 years, increase an ecosystem’s diversity by providing additional shelter for a variety of creatures like salamanders, slugs, snails and lizards.

Law notes that one of the coolest things about working in museum collections is contributing to the team of people who forge a scientific record of life. Study skins, like the mole (Scapanus latimanus) specimen pictured above, hold scientific value in that they strengthen that record, which scientists need in order to detect changes over time in the field. That particular specimen was captured on Santa Cruz’s West Side in 1901, in Lighthouse Field when it used to be known as Phelan Park. As such, it can be used as a point of comparison for more than a century of mole populations on the California Central Coast.

Happily, museums are more than just collections. They are also public exhibits! Take advantage of your chance this month to see these small but significant creatures — up-close, above ground and by the light of day — at our Collections Close-Up pop up exhibit, right by the Museum’s front desk.