A naturalist is someone who studies the patterns of nature. They seek to deepen our understanding of the natural world by observing the interconnected relationships of living things and their environments. Or in other words: Alex Krohn.

“Santa Cruz has the highest density of naturalists per capita of anywhere I’ve been, and I know the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History plays a large role in fostering, supporting, and helping grow that community. That’s something I absolutely support, and something I’m proud to be a part of,” said Alex — a Member, program provider, and collaborative partner of the Museum.

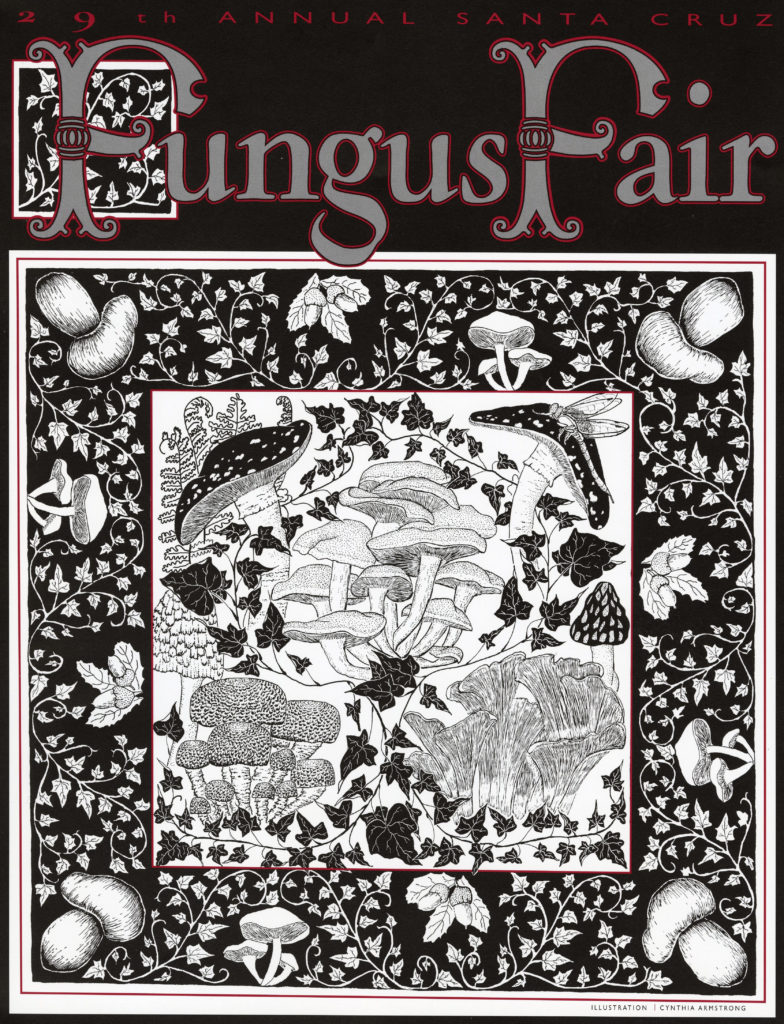

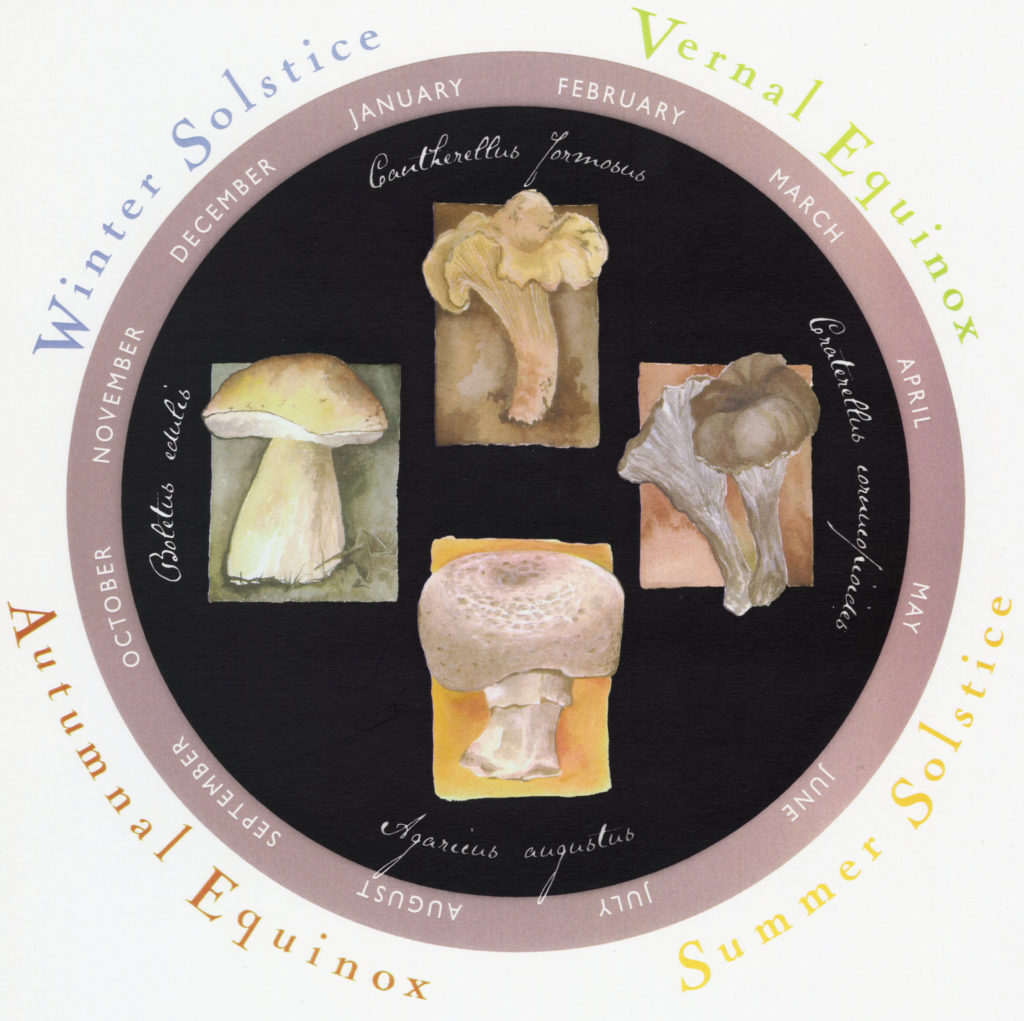

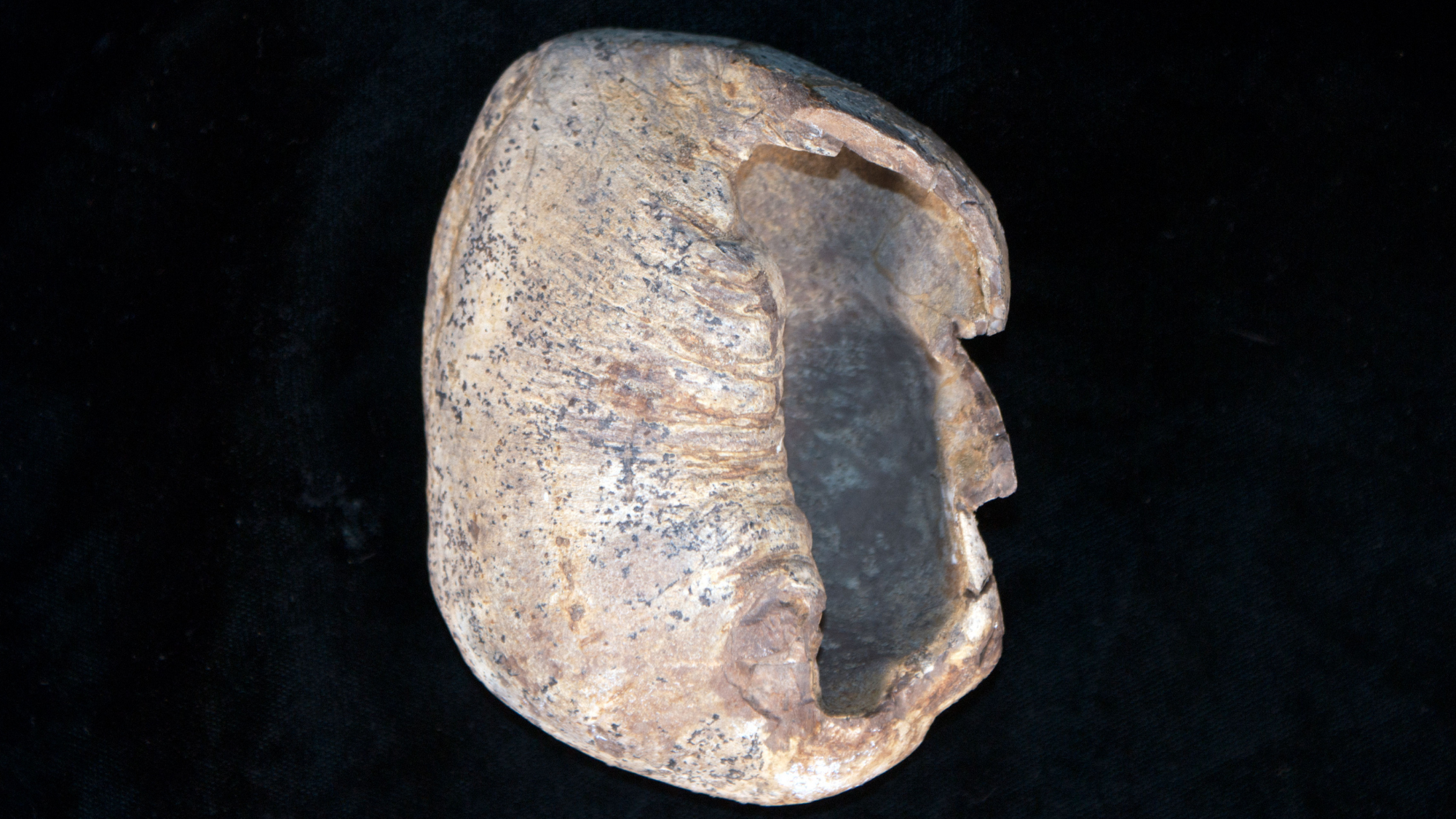

Alex has helped to facilitate a number of loans from the Kenneth S. Norris Center for Natural History to our Museum for events such as our annual Halloween bash, Museum of the Macabre, and exhibits such as the new Mushrooms: Keys to the Kingdom Fungi, January 11-March 1, 2020. He has also led programs for the Museum as a naturalist and frequents our events as a Museum Member. As if that weren’t enough, he is a big fan of our Gift Shop. “So far I’ve done almost all my holiday shopping in the Museum’s gift shop,” he said, which we just love.

Though it is a treat to witness Alex engage on any natural history subject, he is primarily a reptile and amphibian specialist with a PhD in Evolutionary and Conservation Genomics from UC Berkeley. He loves helping connect people with all aspects of nature, both from his post as Assistant Director of the Kenneth S. Norris Center for Natural History at UC Santa Cruz and across the natural lands of Santa Cruz County.

“Santa Cruz County is a truly amazing place,” he said. “We have fantastical species found nowhere else on Earth — from half-dollar sized beetles that only fly at night during the first rains…to multiple manzanita species only present on patches of geologic beach sand that was pushed to the top of a mountain. We have towering redwoods, and sandhill chaparral and coastal grasslands, each more inspiring depending on the day of the week.”

Alex says that his favorite part of his work at the Norris Center is stewarding the collection: “I’m in charge of helping care for, organizing and digitizing more than 130,000 specimens of mostly terrestrial (but some aquatic!) species — from bryophytes to birds.”

Providing access to these collections is paramount for Alex, as is fostering an interest in nature and museums for the students he serves at UC Santa Cruz, many of whom have interned in the Education and Collections Departments of our Museum.

We are grateful to have his support as a local naturalist, important community partner, and engaged Member and friend of the Museum. Explore the wonderful work the Norris Center does by paying them a visit or learning more on their website, and visit some of the mushroom specimens we have on loan from them through our Mushrooms exhibit, opening January 11.