The Central Coast of California is a biodiversity hotspot, and a perfect place to learn more about wildlife. Santa Cruz is fortunate to have a number of city parks and open spaces that attract many different species of birds – all told, 450 different species have been recorded in the county. That’s over a third of all species seen in the entire country! So, if you are interested in getting outside and exploring over the coming days, weeks, and beyond, try birdwatching! It can be fun for all ages, birds are widespread and common across urban and open spaces, and there are a number of effective resources to help those unfamiliar with identifying birds. Birdwatching is a window into lives quite different from our own, but the world of birds, and even their interactions with humans are fascinating and clearly visible once you know how to look for them. All it takes is practice!

Getting Started

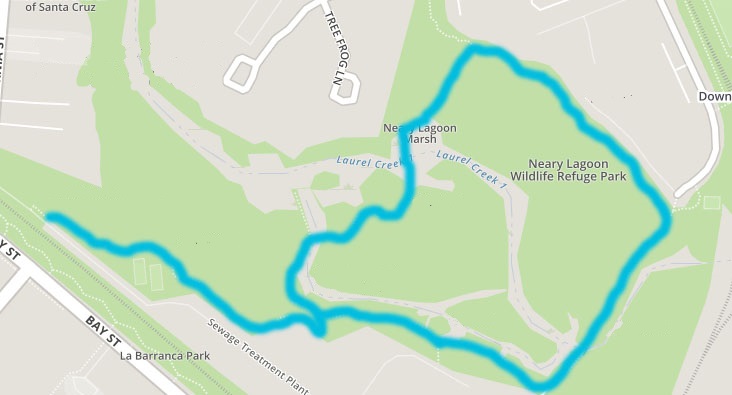

So, you want to see birds. One of the first decisions to make when it comes to birdwatching is where to go. There are certainly places that are more “birdy” than others, but have no fear – you will see birds almost anywhere you go! Bird hot-spots can be found at your local park, creek, or beach, and especially places with water such as wetlands, ponds, and rivers.

Go outside. Do you see birds? You are now a birdwatcher! Armed with nothing but your senses and curiosity, you are now primed to look more closely at the world around you. And if going outside is challenging, you can always birdwatch right from your window. As you begin to identify species and witness interesting behavior, try to record what you’re seeing. Creating a record of your observations is an invaluable skill for naturalists and scientists, and as you continue to birdwatch, you may notice interesting patterns begin to emerge. Below is a list of optional tools to aid with observation, ID, and data recording to get you started. Following posts will explore particular hotspots more in depth and provide tips and tricks to aid with ID, as well as further resources for those interested in flying into the world of birds.

Tools & Resources

- Binoculars can be very helpful, but aren’t always necessary. Many birds are large enough or have distinct enough markings and colors that they can be identified without the use of tools.

- Field guides. These come in all kinds of shapes and sizes, and popular ones include the Sibley, Peterson, and National Geographic guides to birds. There are even app-based guides!

- A journal or notebook to write down observations, sketch what you see, or otherwise record your experiences.

- eBird – a great resource for exploring regions, hotspots, and individual species. You can also upload the species you saw to a database, the largest of its kind on the planet.

- Merlin is an app for smartphones that aids with ID in the field. Just select the date, location, size, colors, and behavior (in trees, swimming, soaring) of the bird you’re looking at to generate a list of possible species.

- Visit the Bird Section of the Museum Store to find guides and gifts for birders of all ages.

Now get out there and start birding!

They’re not gonna watch themselves.

Post by: Spencer