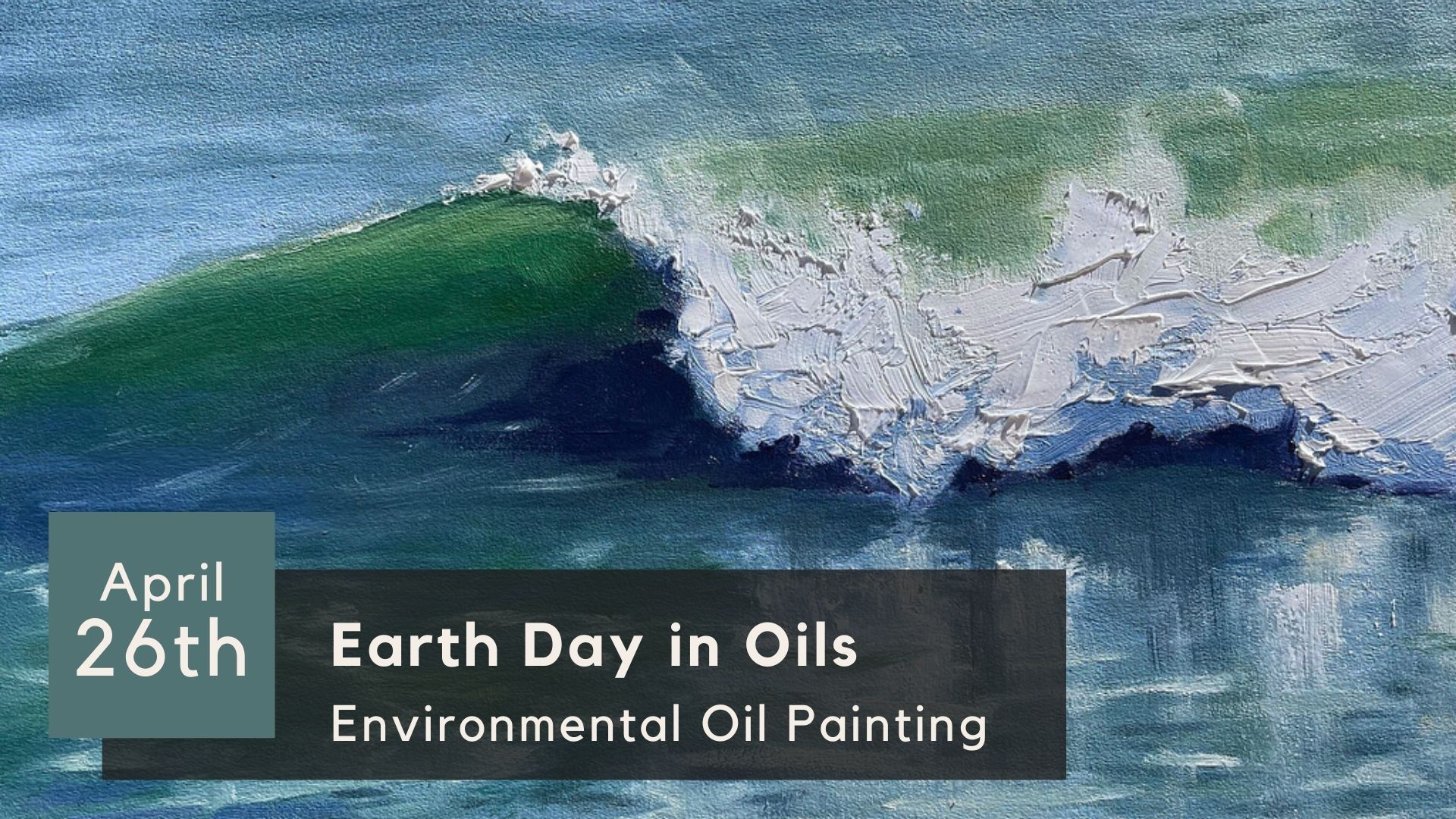

Go green this Earth Day by creating a work of art from upcycled beach glass!

As part of this special seasonal offering, discover the beauty of beachcombing as you create a one-of-a-kind masterpiece made from shoreline treasures. Using local and sustainably-sourced resources, participants will learn the basics of environmental sculpture and design with step-by-step instruction. Transform sea glass, driftwood, and botanicals into unique, coastal-inspired art.

In this workshop, you create an 8×10 sea glass scene that adds a local touch of coastal charm to your home. Join us for a creative experience and leave with a finished framed piece that captures the magic of the shoreline. Perfect for a holiday gift, a personal home decoration, or an activity to be shared with friends or family.

No prior art experience required. Participants will have a completed art piece to take home at the conclusion of the workshop. Open to ages 21+/all experience levels. All art supplies included.

This class takes place indoors. Supplies may get messy, so casual attire is recommended.

📆 Friday, April 25th

⏱️ 5:30 – 7:30 p.m.

📍 Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History

1305 East Cliff DR, Santa Cruz, CA 95062

Materials Fee: All supplies are included in class fee.

Class Fee: $45 – Museum Members receive a special discounted price applied at checkout.

Instructor: Stephanie Spross