An Opportunity for Fire Survivors to Have Their Voices Heard

From residents to researchers, our community has put in countless hours recovering from the CZU Lightning Complex fires of August 2020. In addition to physical work in the burn zone, social scientists are also working towards better understanding how individuals respond to fire emergencies.

Santa Cruz resident Amanda Stasiewicz, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of Wildfire Management and Policy at San José State University currently researching diverse resident experiences with the wildfire events, interactions with fire and emergency professionals, and how to improve the wildfire evacuation and management in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

“In my opinion, the social aspect is the most important part of the ‘fire problem’ to study!” says Stasiewicz. “A lot of people would describe the fire problem as a ‘people problem.’ Much of our wildfire circumstances are a product of over 120 years of fire suppression, the removal of Indigenous populations and land stewardship practices, and forest management policies that were not focused on fire ecology. How societies approach land management questions in fire-prone landscapes directly impacts fire risk or management decisions.”

In Stasiewicz’s early research, she found it fascinating how different people living in the same landscape often have diverse approaches for adapting to their changing environment. “I knew that I wanted to find a way to be involved in that kind of work in the future, to share best practices and the kind of partnerships people were creating to tackle their particular fire problem,” says Stasiewicz.

As a social scientist, her current research aims to provide a platform for individuals’ voices to be heard through an anonymous, in-depth process. She’s recruiting for the CZU Wildfire Event study, where residents impacted by both the CZU and SCU fires can share their experiences and thoughts about how we can improve wildfire management in the future.

“Looking across both fires (CZU and SCU) will allow me to explore management decisions, wildfire impacts, and recovery processes across different vegetation types and social contexts. Exploring how to improve large wildfire management and impacts into the future is particularly timely given our recent high-activity wildfire seasons and how many people are now exposed to wildfire risk. The second phase in a couple months will include a survey to solicit additional feedback. Initial findings will be ready to be shared as early as late winter/early spring!” says Stasiewicz.

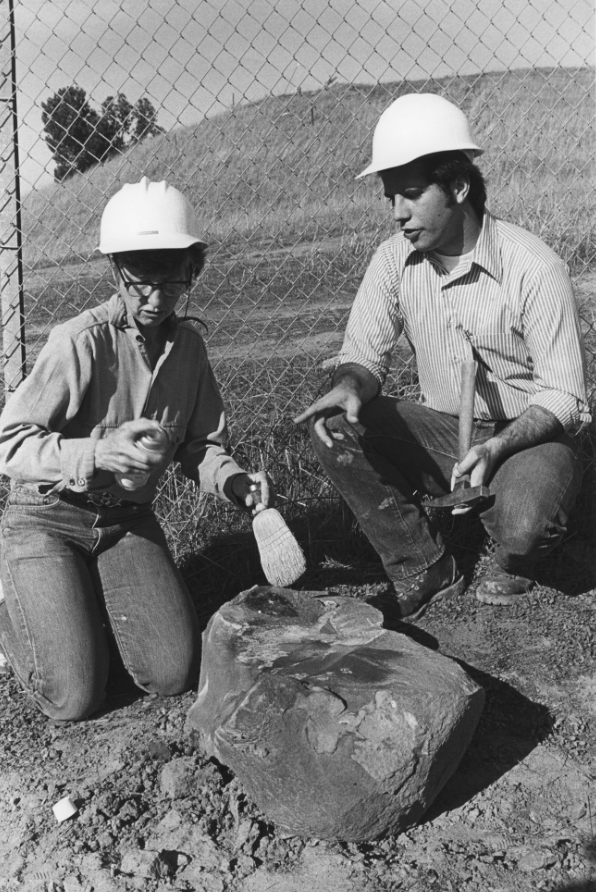

Photo by Jason Seeley.

Have you been personally impacted by the CZU Lightning Complex fires? Consider sharing your perspective! Dr. Stasiewicz conducts interviews which typically take 20-120 minutes and can occur in-person, via Zoom, or by phone. If you wish to hear more about the study or have any questions about participation, please contact:

Amanda Stasiewicz, Ph.D.

Email: amanda.stasiewicz@sjsu.edu

Phone: (208) 874-2800