The safest way to drink radium is not to – and that’s exactly what this month’s Marie Curie All cocktail is all about.

While that seems obvious to us now, one hundred years ago the United States was overtaken by a radium craze. From medicines to makeup, performance art to packaging, people couldn’t get enough of this luminous substance. Today, you can still find antiques that irradiate, whether or not they maintain that iconic glow.

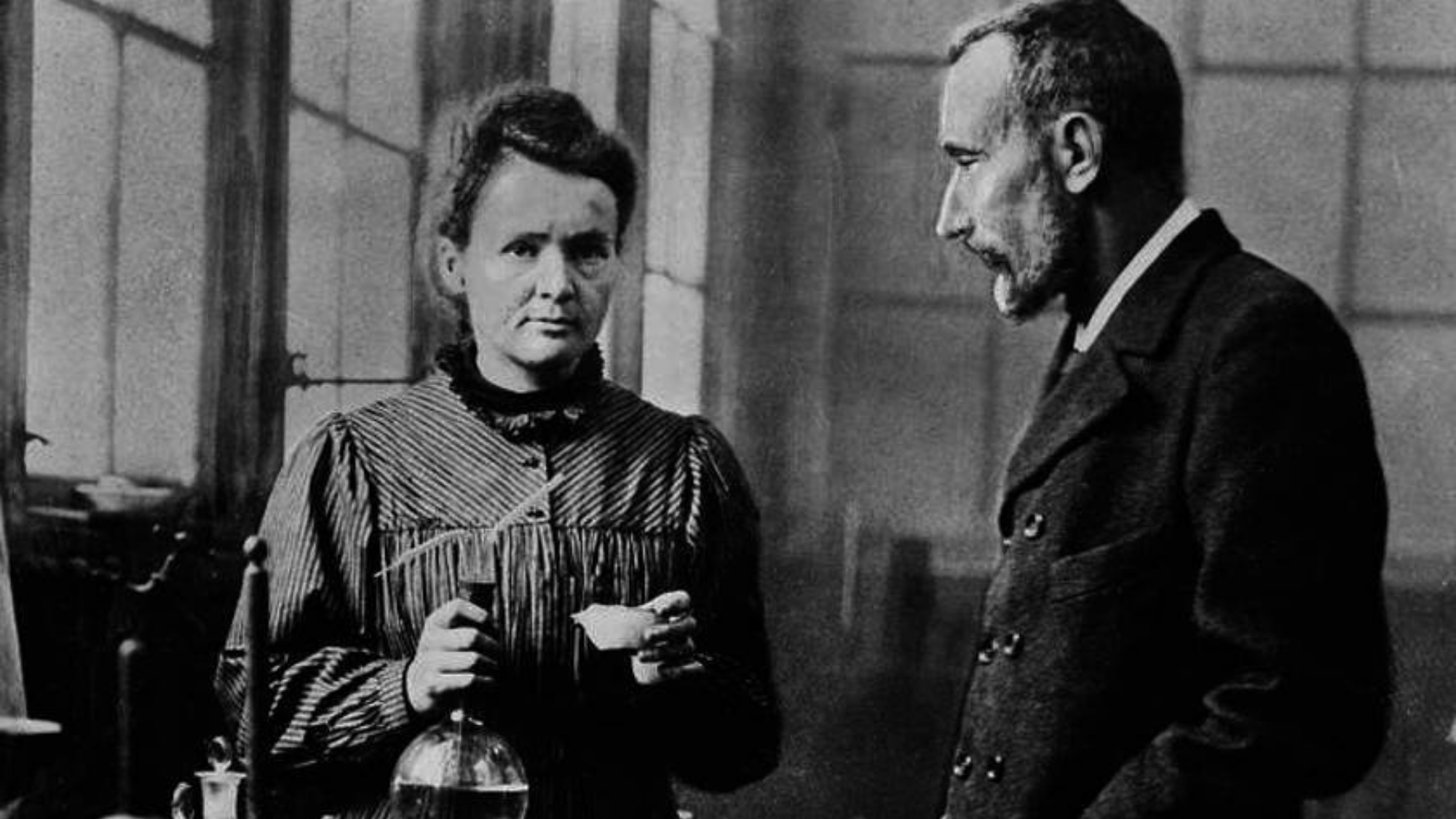

The fad was inspired in part by Nobel Laureate and scientist Marie Curie’s 1921 U.S. fundraising tour for her Radium Institute. Flashing vials of radium in solution was a favorite science communication method of Marie and Pierre Curie, who discovered the radioactive elements polonium and radium in 1898.

Radium, the most radioactive of all naturally occurring elements, showed great potential for unlocking the secrets of the atom. The scientific potential of their discovery did not stifle the timeless magic of good lighting; Marie described the duos’ lab looking as if it was full of “fairy lights” and took to sleeping with a vial of radium chloride’s soft blue glow at her bedside table. (for an up close and personal look at the scientists lives’, check out Lauren Redniss’ Radioactive). Refusing to patent any of their work, the Curies were especially excited about radium’s potential humanitarian applications, such as it’s capacity to kill off diseased tissue.

Of course, it also kills healthy tissue. Most famously, bodies of the watch dial painters at U.S. Radium Corporation starting around 1917. These Radium Girls were told that the “Undark” paint they used, a mixture of radium powder, zinc sulphide, and other elements, was safe. Even while their managers and scientists took various precautions, they encouraged their workforce to lick the end of the paint brushes for sharper lines. After a great deal of suffering and gaslighting, from radium rotted jaws to broken hips to doctors blaming their illnesses on syphilis, five of these women settled a lawsuit against US Radium in 1928. While too late to save them from radiation sickness, this case and it’s publicity helped inspire government initiatives for worker and consumer protections.

To carefully carry forward that soft green glow associated with commercial radium products as well as the Curie’s commitment to healthcare, this twist on a classic tropical cocktail avoids radiation AND includes an essential vitamin. Riboflavin, also called vitamin B2, fluoresces yellow under black light (a feature which today’s scientists are exploring as a safer way to track the spread of respiratory diseases).

Carefully mixed with blue curaçao, we get a fluorescent green to brighten, or perhaps Undark, your next spooky season happy hour.

Ingredients

- 1.5 oz light rum

- 1 oz blue curaçao liqueur

- .5 oz ginger liqueur

- 2 oz pineapple juice

- .5 oz lemon juice

- .5 oz orange juice

- 1 oz cream of coconut

- Pinch vitamin B2*

Recipe

- Mix all ingredients in a cocktail shaker full of ice.

- Adjust B2 for color preference – a ratio of ¼ of a 100 mg supplement per 1 oz blue curacao keeps things softly green.

- Pour in a tall glass, tiki or tom collins style, and garnish with pineapple wedge and cherries.

*According to the NIH, “Intakes of riboflavin from food that are many times the RDA have no observable toxicity, possibly because riboflavin’s solubility and capacity to be absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract are limited . . . The limited data available on riboflavin’s adverse effects do not mean, however, that high intakes have no adverse effects, and the FNB urges people to be cautious about consuming excessive amounts of riboflavin [3].”

Explore minerals that can kill in our Rockin’ Pop Up and be sure to join us for this year’s Museum of the Macabre where we’ll explore deadly plants, potions, and poisons.