Dusting feathers, labeling fossils, freezing foxes. Checking conditions, inventorying subcollections, replacing boxes. Measuring shelves, sorting photos, scanning files. The steady hum of the dehumidifier over the muffled murmurings of distant meetings. Collections work lives at the intersection of the physical and the abstract, where a great deal of our time is devoted to the preservation of our specimens, objects, and artifacts so that they continue to be available for the creation of knowledge.

What then, is collections work when not at the museum?

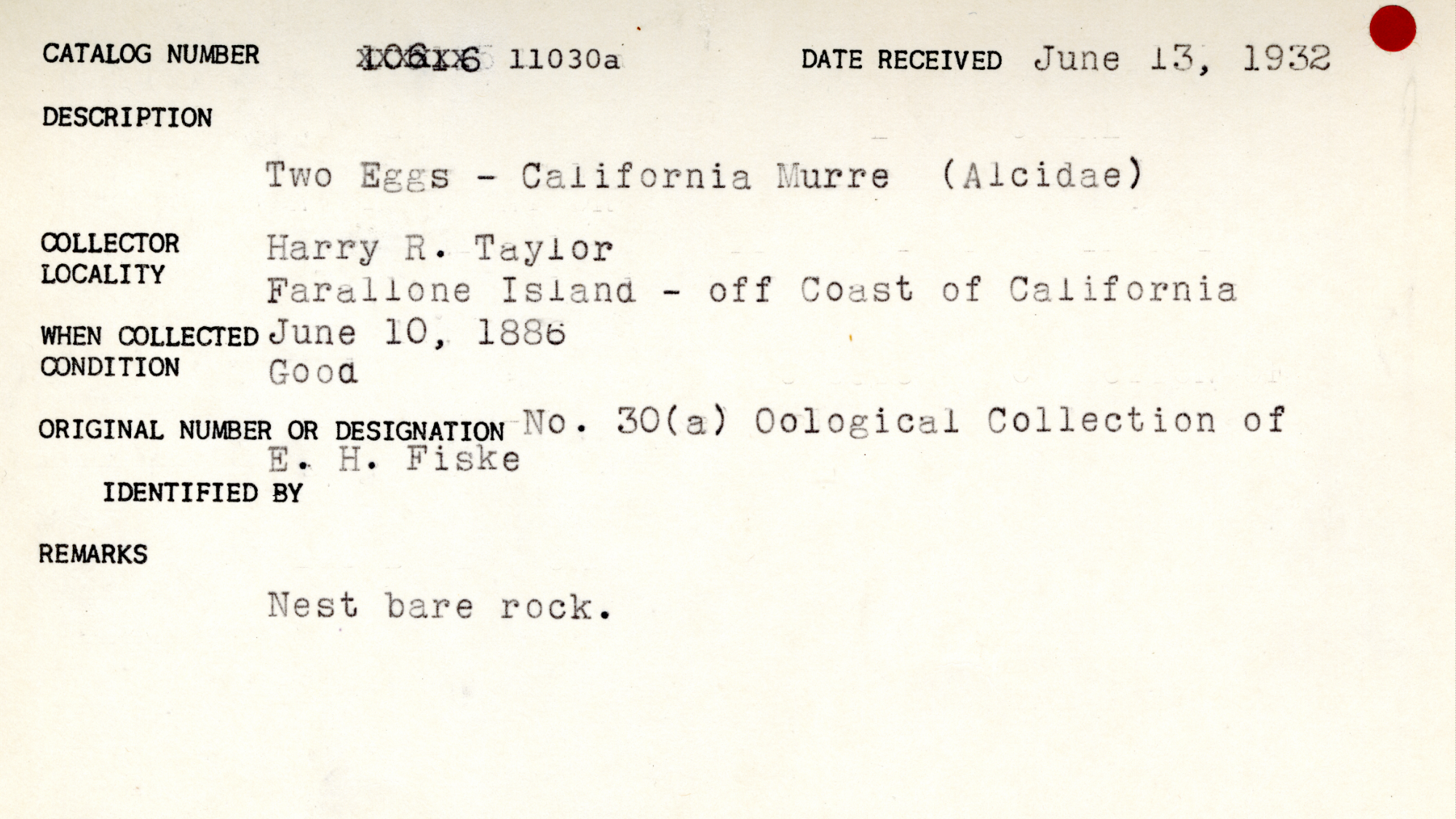

A critical part of our ongoing efforts is the expansion of access to our collections through the process of digitization. So, on the eve of the shelter in place in order, collections assistant Isabelle West spent hours upon hours scanning as many of our undigitized ornithology catalog cards as she could so that we could continue this important work.

Digitization is the conversion of analog data to digital data. For many of us this is an easy definition. But collections are as diverse as their contents, and each museum must decide if their digitization work focuses on specimens and labels, or extends to field notes, accession records and more.

For us, digitization is twofold: It includes conversion of our foundational records, (catalog records and the accession paperwork that supports our ownership of our cataloged items) while building infrastructure and staff expertise in specimen photography. With the latter unavailable, the former becomes the focus.

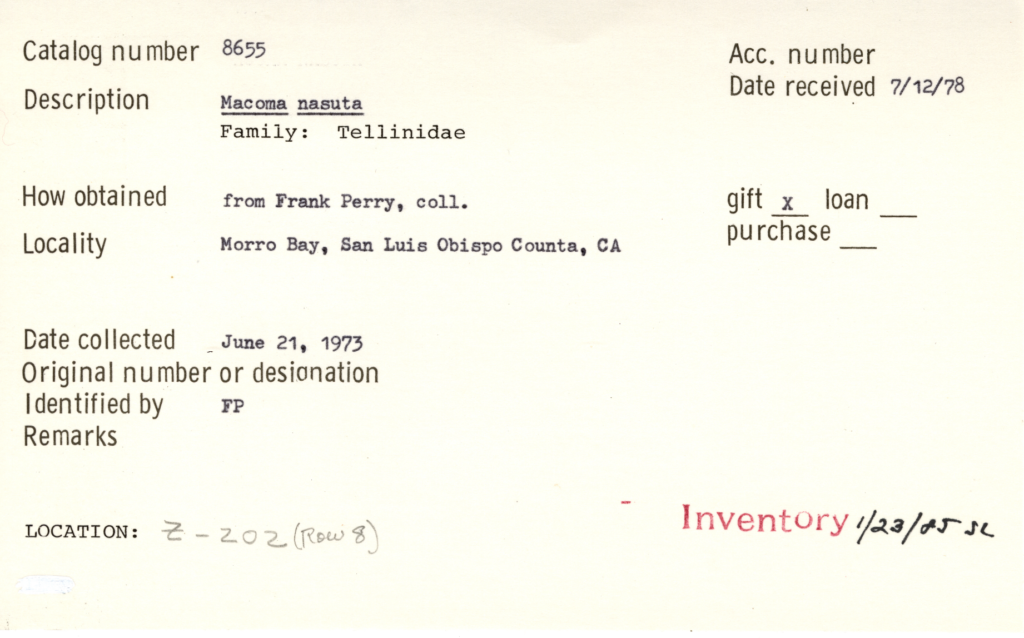

Transcribing these cards, which at present focus on eggs and nests, Isabelle gets up close and personal with the ins and outs of decades of record keeping. This is one of her favorite parts about the process – getting to be part of the collaborative conversation that captures as many as three or four voices describing, updating, and inventorying information about this nest, or that clutch of eggs. She enjoys observing trends in collecting, like being able to see that almost all of our eggs were collected between 1880 and the mid 1890’s, or that the majority of the eggs were collected in June. Happily, her work means we’re headed to a place where museum patrons, researchers, and the wider public can also make observations about our data.

That data is critical to the value of scientific collections; the who-what-when-where details of collecting. A big challenge to creating good records, Isabelle points out, is when there is little to no data, or when what’s there presents puzzles like the red dot stickers that were used to signify that some form of fumigation treatment was applied to the specimen.

And while Isabelle is leading this charge, she’s not alone. Given the hundreds of records, record digitization is incorporated into all collections-related workflows. Recent projects include work by former intern Jordan Bakhtegan, who digitized and inspected specimens in our mollusk collection, and our ongoing ethnographic record digitization and review project led by Dr. Alirio Karina, PhD, whose scholarship interrogates practices of representation in ethnographic museums.

This process of digitization isn’t new to us – museum staff have undertaken various computerization projects over the years. Two of my favorite 80s-era relics are an IBM keyboard box used as temporary housing for a set of eggs in the teaching collections, and a brittle black binder entitled “Usage of Computers in Museum Collection” – both of which attest to the early interest of museum staff in taking advantage of the digital age. However, various efforts have fallen victim to different kinds of data decay – disks can get corrupted, databases can crash, and data input documents can get misplaced. A critical part of digitization is preservation, and our present commitment to collections stewardship is anchored, in part, on an industry standard collections management database, complete with physical and cloud backups, that unites all of our laboriously created collections data under one (digital) roof.

But stewardship is as much about sharing things as keeping them safe.

Historically we’ve done this through exhibits, pop ups, research appointments and more. More recently, we’ve added elements like the Laura Hecox Collections Guide or the Naturalist’s Scrapbook. Now that we are more aggressively pursuing digitization, we can also start looking at how to take part in the vibrant global conversation around the data mobilization or use.

As large scale data aggregators like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), Integrated Digitized Biocollections (iDigBio), Vertnet come into their second and third decades, researchers are reflecting not only on the history of digitized collections, but also the ways they are transforming how we ask questions about the world around us. An analysis of the past ten years of scholarship utilizing publicly accessible biodiversity databases richly depicts the triumphs and challenges of the field. Echoing UC Berkeley paleontology professor Charles Marshall on unlocking the value of fossil collections, we are excited for the ways that digitization will not only bring our collections into deeper conversation with the public, but also with the larger pursuit of knowledge.