Starting in March, the Museum is premiering a new blog by Collections Specialist Kathleen Aston called Collections Close-Up, which will feature items from our Collections that are rarely, if ever, on display. In addition to featuring the items in our newsletter and on social media, the Museum will display the items in our galleries in a special exhibit that will change each month.

For March, we are taking a closer look at the Museum’s echinoderm or “spiny skinned” animal collections. Phylum Echinodermata consists of more than 6,500 living species that can be divided into five classes, including sea stars, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, sea lilies/feather stars, and brittle stars. They tend to exhibit a characteristic five-sided, radial symmetry, with arms radiating out from a central body disk. Echinoderms have a unique water vascular system which carries liquid throughout their bodies in a series of tubes, and achieves movement through hydraulically driven tube feet. Additionally, echinoderms have mutable connective tissue, which allows their bodies to quickly transition between rigid and pliant states, meaning they can maintain a variety of postures with no muscular effort.

Now, sea stars like the ones you can find in our touch pool belong to the Class Asteroidea, meaning star-like. Here we are taking a closer look at Class Ophiuroidea, whose name comes from the ancient Greek word for serpent. Members of this class are commonly called brittle stars for the fact that their arms, which regenerate, easily break when caught. Brittle stars are the most abundant echinoderms, and outnumber sea stars both in number of species and number of individuals. They are often found in thick carpets along the ocean floor, where they tend to feed on small organic particles. In comparison, sea stars tend to feed on relatively larger prey such as clams or snails. Though similar looking, brittle stars structurally differ from sea stars in several ways. Perhaps the easiest distinguishing feature is that while the arms and body of sea stars tend to merge gradually into one another, the long and snake-like arms of brittle stars are distinctly off-set from the disk of the body.

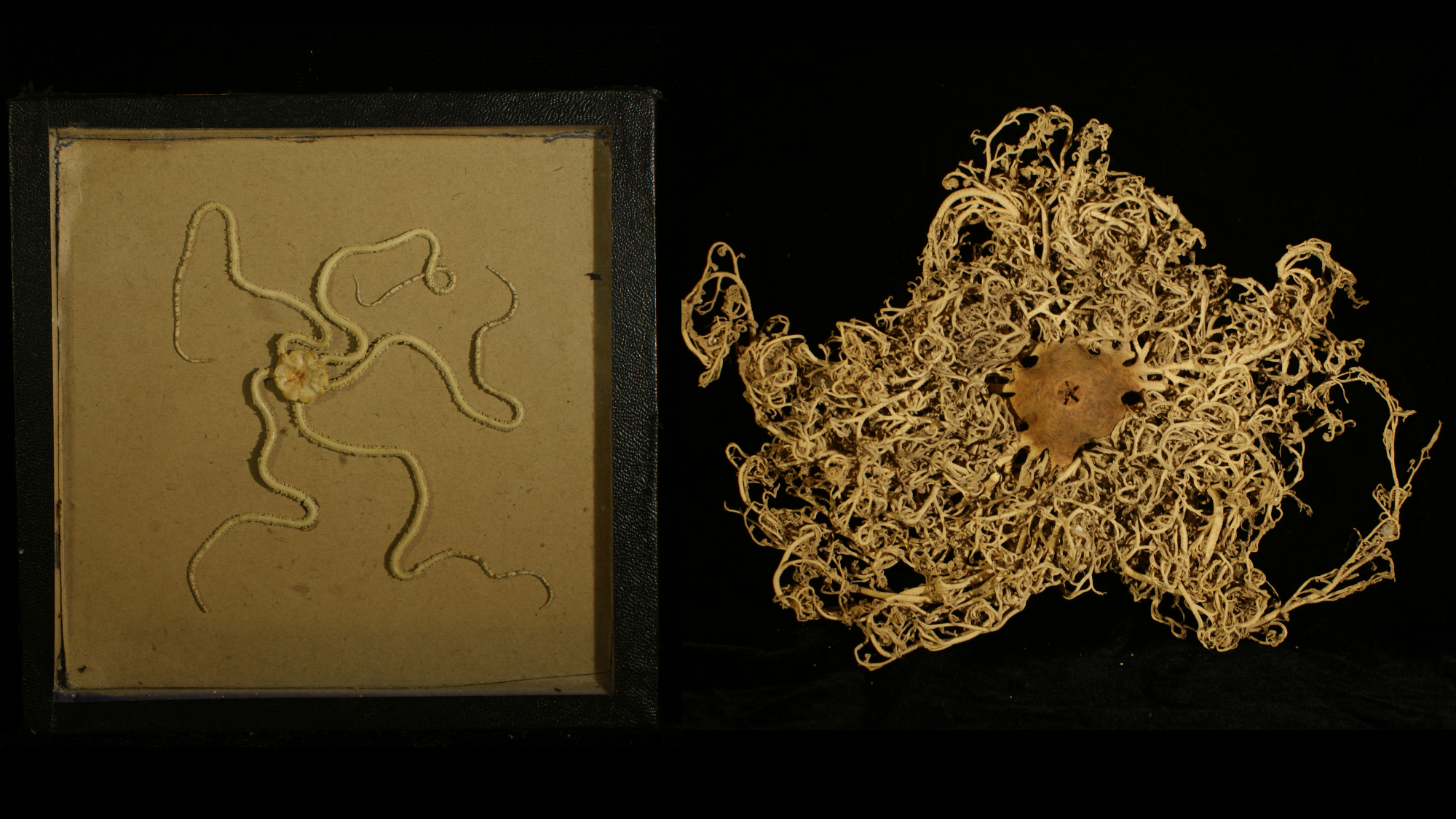

One representative of class Ophiuroidea in our collections is this individual Amphiodia occidentalis (above left), which was collected in Pacific Grove in 1939. First described in the 1860s, this species of long-armed brittle star clearly shows the snaky and sinuous arms attaching to a distinct body disk. As this species has been observed on the Central Coast to avoid areas with wastewater, it can be used as a bioindicator for water quality.

But Class Ophiuroidea has more to offer: basket stars. In basket stars, like this Gorgonocephalus eucnemis (above right), the creature’s five arms are branched into smaller and smaller subdivisions that give the impression of a tangled basket or nest. Once prey is trapped in these branches, it is immobilized by a secretion of mucus and slowly coiled by the branches to the basket star’s mouth. Basket stars are cold-water creatures, and are found in the Arctic and Antarctic oceans as well as the deep-sea worldwide.

In museum collections, echinoderms are generally preserved as dry specimens when they are going to be studied for skeletal examination. Wet specimens, or preservation in alcohol-based fluids, are preferred for the study of soft tissue, but are also more generally versatile. Modern methods of collecting and preserving echinoderms encourage video documentation prior to preservation, to better capture information regarding behaviors like locomotion and feeding.