Fossils bring the past to life, but they can’t always take us there. While the smallest sliver of ancient bone can hold the key to scientific mysteries, it can’t always immerse us in the ancient world itself.

Enter the work of the paleoartist, the illustrator who excels at engaging contemporary science to create vivid depictions of forgotten worlds. The museum is delighted to share brand new imagery from one such local artist, Mason Schratter. Mason, a graduate of Cal State University Monterey Bay’s Science Illustration certificate program, spent this fall focused on bringing our Pacific mastodon skull to life.

A long time fan favorite, the mastodon skull has presided over our exhibit halls since it was first wrenched from a local creekbed in 1980. One of the few documented mastodon finds from Santa Cruz County, the skull is also the most complete mastodon fossil found locally. In the illustration below, you can see Mason’s straightforward depiction of the mastodon as a specimen.

Specimen illustrations like this are incredibly useful for exhibiting extinct animals to the general public. They help us envision aspects that are missing, such as the tusks that had to be recreated for the display. It also helps us focus on significant anatomical elements that might be harder to discern for the average viewer, such as a clear visualization of the proper orientation of a mastodon tooth: it is the lumpy parts that peak out of the jaw bone, rather than the longer, more stalk-like roots of the tooth. Detailed specimen depictions can be useful for scientific papers, while stylized illustrations can be useful for posters and merchandise.

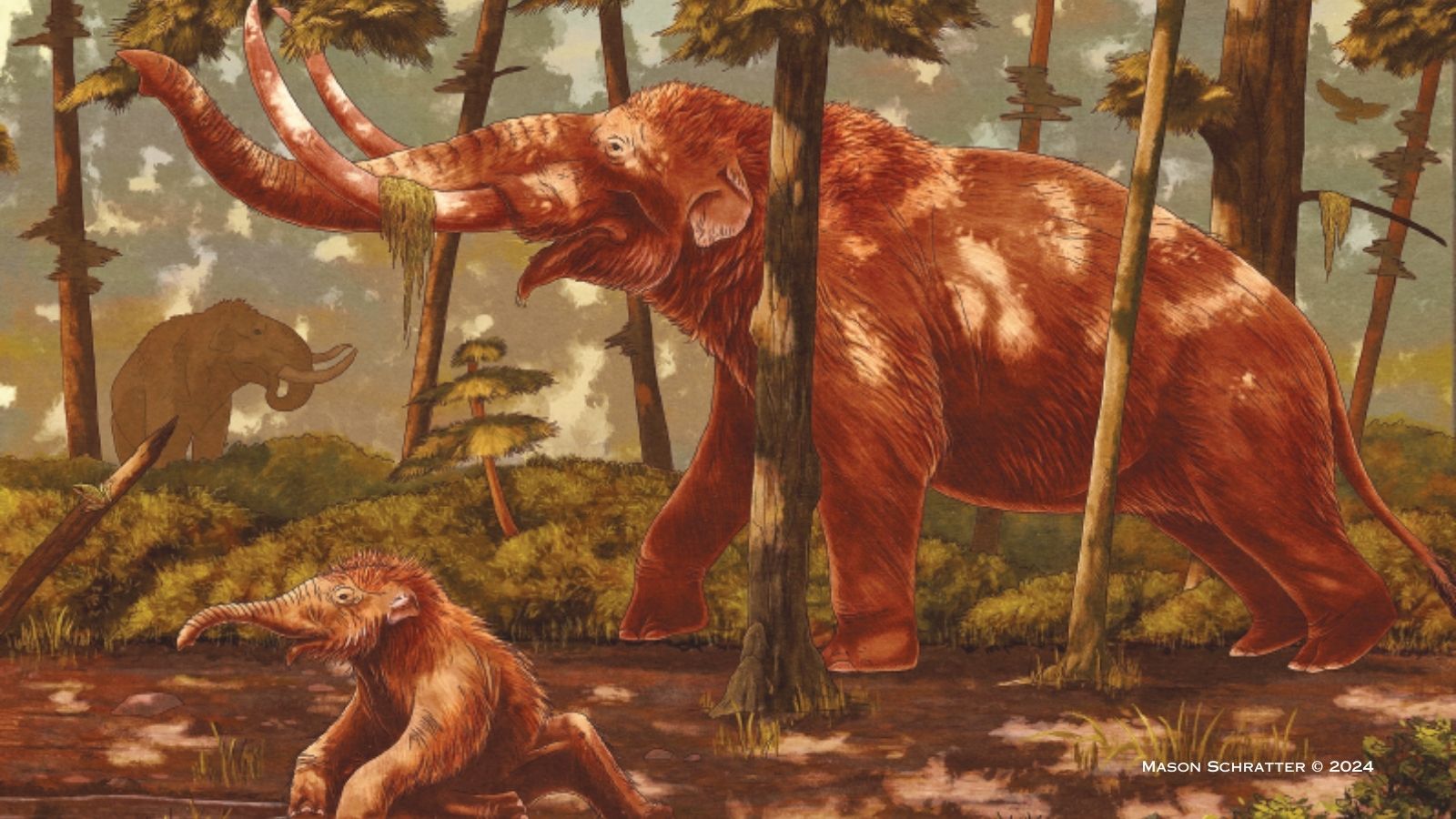

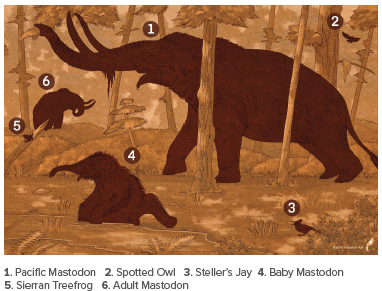

But paleoart is more than just illustrating specimens, it is the art of using science to inform the viewer of prehistoric life – living creatures in their environments. Enter the lush landscape of Mason’s mastodon scene, depicting a juvenile mastodon at play alongside a stream. Dappled sunlight drifts across the soft textures of rich flora and furry fauna, luring the viewer into the hazy ambiance of an ancient forest. The playful pose of the young mastodon is especially enchanting, reminding museum goers that despite the hulking size of our mastodon skull, the animal it came from was not even fully grown.

The immersive aspects of this landscape wouldn’t be worthwhile if not for the science that informs the artistic choices – Mason has adult mastodons browsing for food amongst Douglas firs because pollen records show that Douglas firs were prominent in local forests during the Pleistocene epoch (2.58 million to 11,700 years ago). He chose to include animals such as the Steller’s jay and the Sierran treefrog, known from the fossil record to have existed contemporaneously in comparable habitats, to emphasize that while these mastodons may feel impossibly stuck in the past, they co-existed with animals that are part of our present.

Paleoart can do more than transport us, it can also surprise us, upending misplaced notions of distant eras. Viewers may notice the absence of ice in this vision of the “ice age”, the nickname by which the Pleistocene epoch is more commonly known. Rather than being a single stable cold period, the Pleistocene was characterized by cool periods of advancing glaciers across the globe, with warmer interglacial periods. Despite not being frosted with a constant layer of ice, Pleistocene Santa Cruz would still have been generally cooler than it is today.

We love these depictions of our mastodon, but we’d love help expanding our mental landscape of Pleistocene Santa Cruz. To help us out, make like Mason and the mastodon, and explore illustrating your own ice age creatures!

Get started by going to the contest page on the museum’s website. Need inspiration? Check out this video by museum educator Hannah Caisse on drawing dinosaurs for a deeper dive into paleoart’s depiction of dinosaurs, or explore these hands on guides and classic examples of paleoart outside of the dino mold.