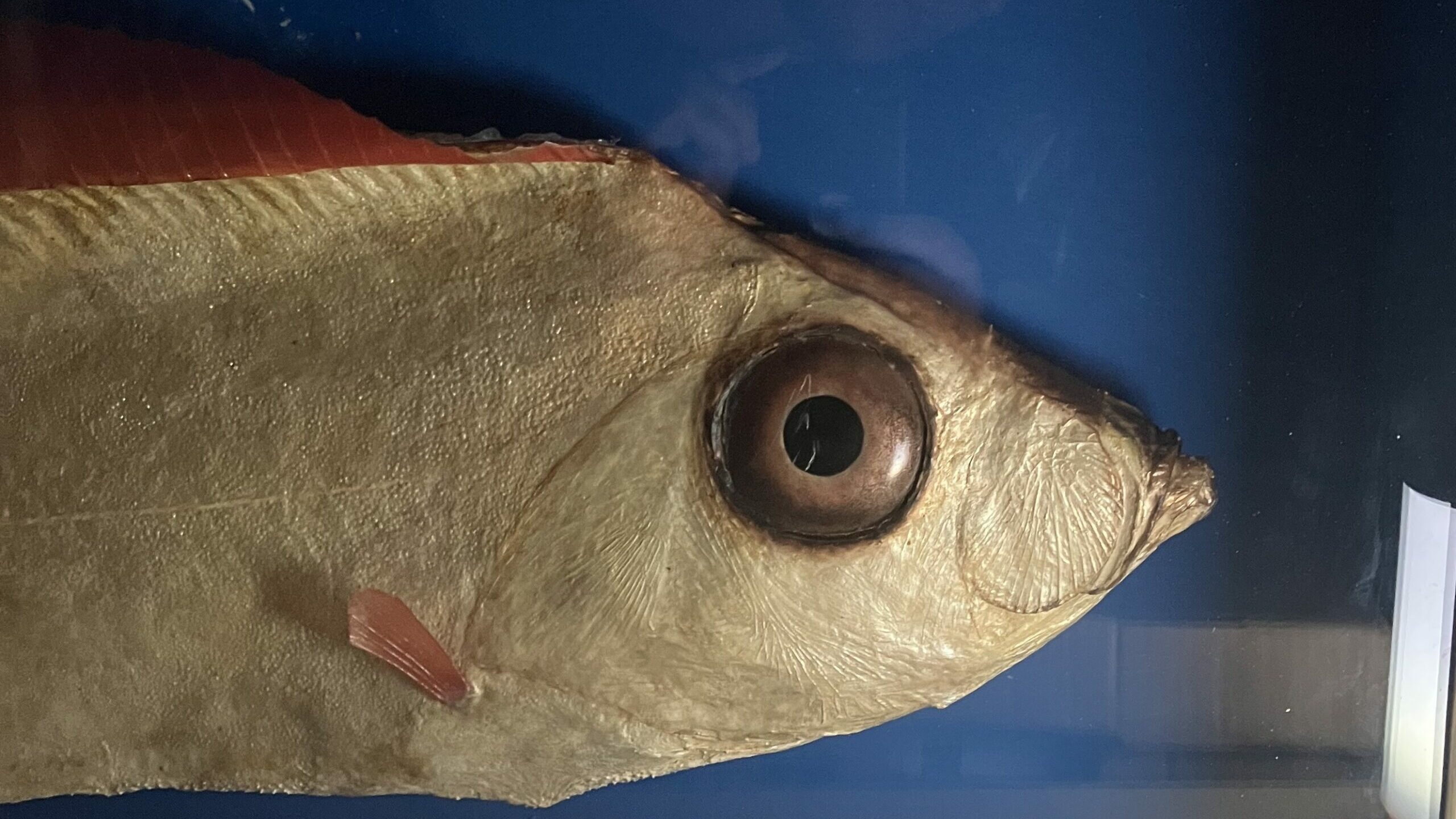

Natural history museums are no strangers to strange fish. Our museum is no exception, even when it comes to exceptional specimens like our Tapertail ribbonfish (Trachipterus fukuzakii) cast. Over six feet of silvery skin punctuated by coaster-sized eyes that seem at once startled and startling, and topped with an unbelievably red dorsal fin, this cast preserves the true-to-life details that defined this curious catch just as it emerged from the Monterey Bay more than 80 years ago.

In early May 1938, local fisherman Gus Canepa was out on the bay going about his business of trawling for cod. While local news reports differ on the depth, at some point between 2000 and 750 feet he caught an unusually long but eerily thin, distinctly un-cod-like creature. Arriving at the wharf, he immediately shared it with his fellow fisherman. All were intrigued, with one older Italian man claiming to have seen such a specimen only once before, decades prior off the coast of Genoa.

News spread fast, and inspired the arrival of Dr. Ralph Bolin of Hopkins Marine Station, who first identified the specimen as the illustrious Trachipterus rex-salmonorum, or King-of-the-Salmon. By this time the fish had been transferred to the possession of what was then the Santa Cruz City Museum, led by ocean enthusiast Harry Turver. The local naturalist community was abuzz with excitement – remarking especially on the thinness of the fish, which seemed not to exceed an inch in length anywhere along its body, and the large eyes, which aided in the gathering of minimal light as the animal explored the ocean’s mesopelagic, or twilight zone. The red fins were another source of interest, a feature historian Randall A. Reinstedt in his Shipwrecks and Seamonsters of California’s Central Coast has argued might help explain historical accounts of sea serpents with red manes.

The enthusiastic interest was shared by the Smithsonian Institute, which, having heard the news of the fish, asked to collect it. In bargaining with Mr. Turver, they emphasized the rarity of the specimen and its importance – at that time they only knew of two specimens of the species, and each had been badly mangled. For the sake of science, and a high quality cast, Turver agreed. The original was packed in 200 pounds of dry ice and shipped east by train, where the Smithsonian preserved it in a tank of fluid. Subsequently re-identified Trachipterus fukuzakii, the specimen is available to researchers to this day.

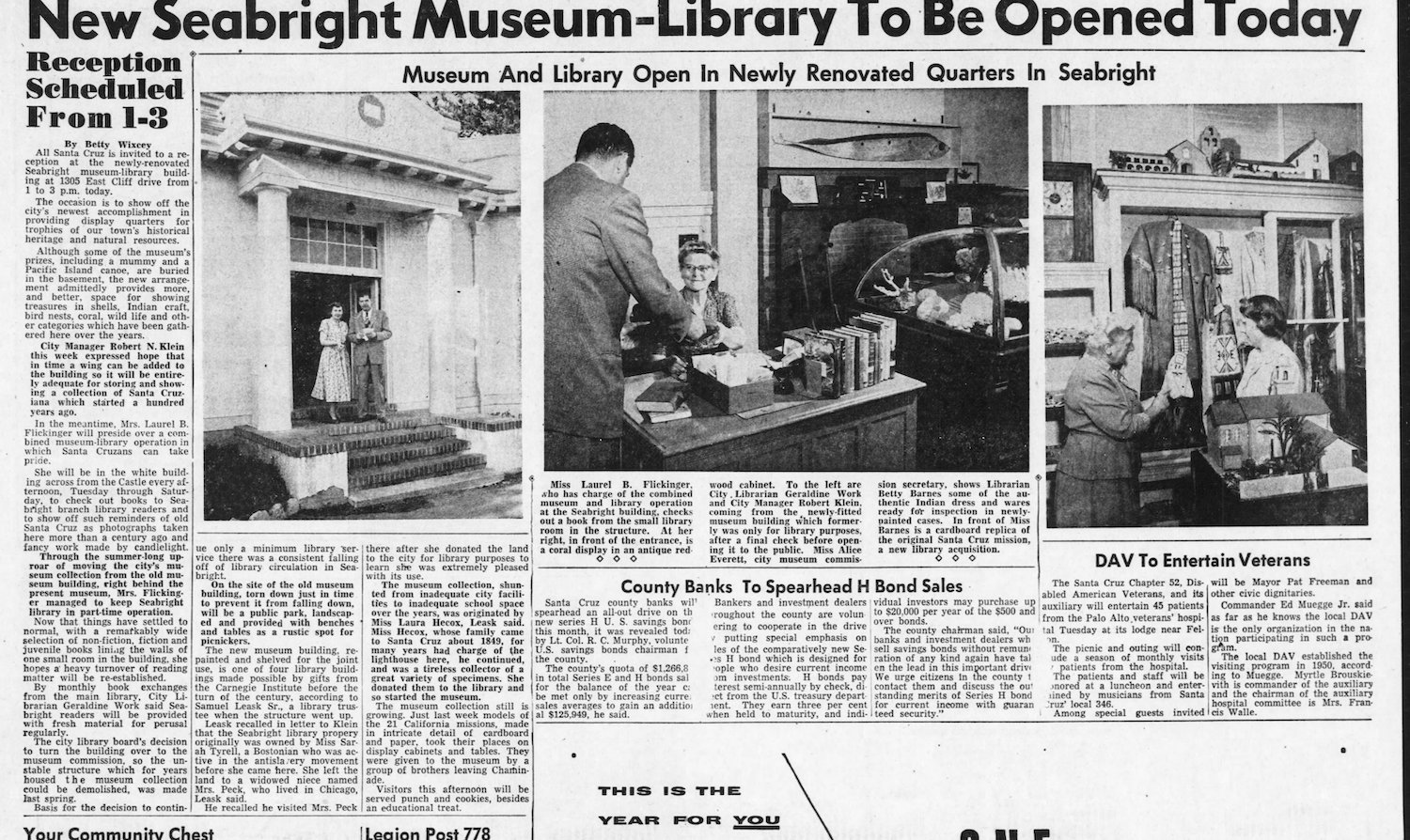

The same is true of its cast, which has delighted museum visitors since its 1942 arrival (you can even see it in the 1954 photos of opening day at the “Seabright Museum-Library”). A semi-permanent display feature in our exhibit halls, it is currently being refurbished by conservator Alicia Goode to make sure that such a rarity can be shared with our community for another eighty years and beyond.

Even as the cast has become a familiar face to the museum community, the species continues to puzzle scientists. A 2021 review of the Trachipteridae, the ribbonfish family, emphasizes how much work remains to be done to understand these strange fish. This makes it an even better fit for this fall’s Maritime Mysteries and Monsters special exhibit, where the ribbonfish’s re-emergence serves as a testament to the ongoing enigma that is life in the ocean.