Not all that glitters is gold — sometimes it’s benitoite! So discovered prospector James Couch, when in 1907 he encountered some sparkling specimens of what would one day become the California state gem. While gold looms large in the story of our state, the unique geology of California has gifted us many other magnificent rocks and minerals. From cinnabar to serpentinite, we are delighted to share these with the public once more in our classic California minerals exhibit. We are fortunate enough to have one specimen of rare benitoite on display, and for this month’s close-up, we’ll zoom in on our only other specimen, safely secured in storage.

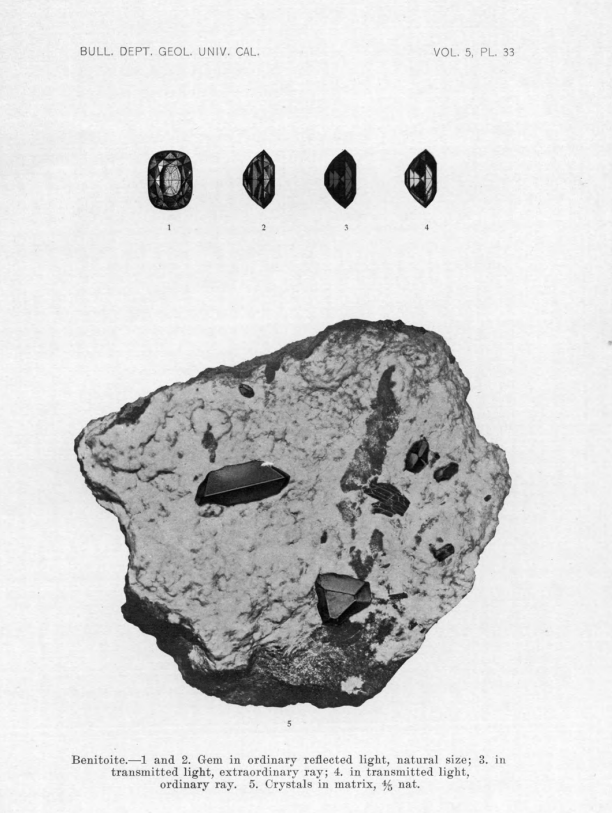

Our second benoite specimen is hosted by a chunk of blueschist that amounts to the size of a large hamburger. Brilliant blue sparkles alert us to the presence of benitoite, or barium titanium silicate (BaTiSi₃O₉). These are nestled alongside black sprinkles of neptunite in a white, almost fuzzy looking layer of natrolite. Blue, black, and white, each of these substances is its own mineral, a naturally occurring inorganic element or compound with a characteristic structure.

These minerals and their blueschist host rock come from the guts of the southern end of the Diablo Range. Millions of years ago, unusual combinations of hydrothermal fluids seeped into the cracks of the blueschist found within metamorphosed serpentinite, forming a variety of rare minerals including benitoite, neptunite, natrolite, joaquinite and others. And while benitoite is found in a few places around the world, this section of the California Coast Range geologic province in southeastern San Benito County is the only place in the world where gem quality benitoite crystals are found.

It’s also the first place where benitoite was found. There are some complex claims to the initial discovery, but the most widely accepted story begins with failed melon farmer James Couch prospecting outside Coalinga on behalf of investor R. W. Dallas. In December of 1907, Couch noticed some blue sparkling stones he thought to be sapphire. In the subsequent months, Dallas looped in a few dealers and gem cutters, who offered different identifications, including an expert in Los Angeles who thought it was volcanic glass (perhaps because of it’s conchoidal fractures). By the time a sample made its way to San Francisco, a lapidary who thought the stone was spinel showed it to a friend, who sent it to UC Berkeley mineralogist Dr. George Louderback.

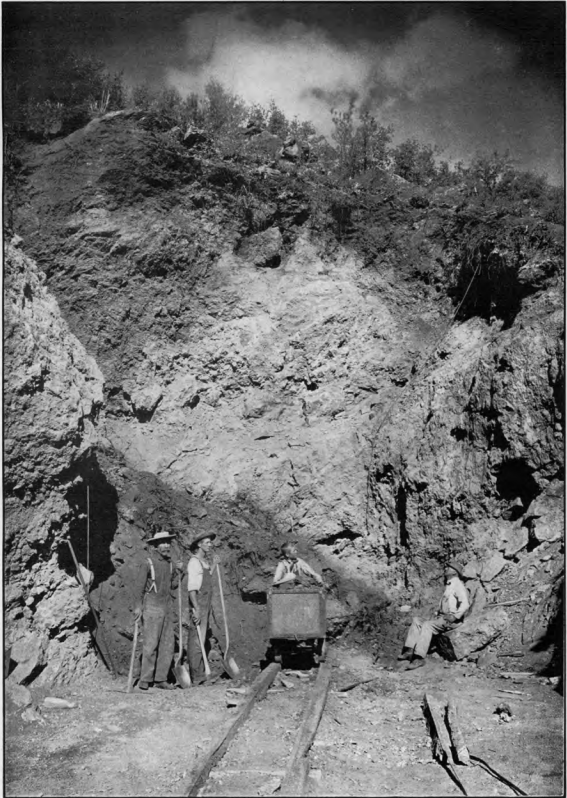

Dr. Louderback investigated the sample, finding it too soft to be either spinel or sapphire. Upon examination, Louderback identified the specimen for what it was – a new substance to science, and named it Benitoite, after the San Benito river which ran through the area of the mining claim. He soon journeyed to the Dallas Mine, where operations had already started, to study benitoite’s geological context. The paper he published describing benitoite’s mode of occurrence also includes the first published photos of benitoite and early photos of the mine.

The paper describes a lot of the properties that make benitoite exciting – including the high refractive indices and strong dispersion that make it especially sparkly (although you have to go elsewhere to learn about benitoite’s stunning fluorescence). It is still described by many sources as one of the “finest” descriptions of a new mineral species to be written. It’s worth noting that benitoite, while new to science, was nonetheless the embodiment of a scientific prediction that had been made decades prior. It exhibits a ditrigonal-dipyramidal crystal habit, a shape that looks sort of like someone glued the bottoms of two triangular pyramids together, within the hexagonal crystal class. This was the first time such a form was found naturally occurring, one of only thirty-two possible classes of crystal shapes mathematically predicted by Leipzig crystallographer J.F.C. Hessel in 1830.

Even as the true nature of benitoite was unfolding, commercial operations quickly emerged at what was first called the Dallas Mine. Over the decades the mine has seen varying techniques and levels of productivity. In the earliest years, folks were after the largest possible gems and they wanted them fast. This meant hacking off a lot of big knobs of crystal that were initially covered, due to the way the mineral veins had formed within the blueschist, in a fine layer of natrolite. Waiting to dissolve the natrolite in acid, which could happen with no harm to the benitoite, took too long. This meant that a lot of well crystalized mineral specimens within their original rock matrix were broken up and made into gems. Fortunately, some whole specimens remain, and the museum purchased the specimen featured in our Collections Close-Up from San Francisco based J. Gissler in the late 1930s.

Our display specimen was also purchased in the 1930s. This specimen has been exhibited since 1985, the very year that Californian’s made benitoite their state gem to celebrate its beauty and uniquely California story. And though the history of this mineral is part of it’s charm, mineral discovery is not a thing of the past. Scientists continue to discover new minerals as the result of current field work, or even through fresh understandings of preserved museum specimens.